by Jackie and Alex Jackie’s story, like that of so many, begins with domestic violence, violence she weathers with the help of her sex work. Her son’s father continuously uses abusive financial tactics, severing any ability she’s ever had to gain ground in her life. Her ten-year-long saga has kept her working under the table,… Continue reading Holy Shit: Adventures In Survival Sex Work And Stimulus Checks

Category: This Time, It’s Personal

Sex Working While Jewish In America

We are witnessing the blossoming of a white nationalist nation. Being the person that I am is not easy in the United States right now. It’s not easy for my friends, my family, or millions of Black people, Jews, and LGBTQI people. I’m an Iranian, Tunisian, French and Jewish sex worker. I immigrated from France… Continue reading Sex Working While Jewish In America

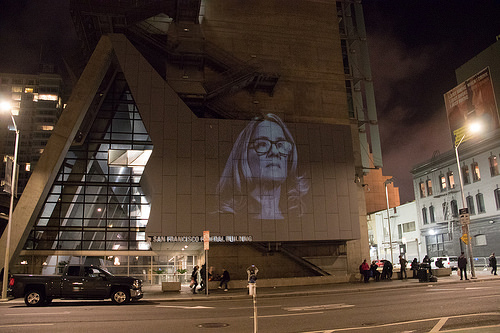

Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Will Kill Disabled Sex Workers Like Me

A few years back, I woke up, looked at my arm, and thought I was in a nightmare. My arms were covered in rashes of tattoo-dark blood blisters so thick my skin looked burgundy-purple from a distance, and bruises, the flesh so swollen it looked like I had been in a car wreck. I had… Continue reading Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Will Kill Disabled Sex Workers Like Me

Deep In The Shadows: Working Trans Without Disclosure

Being a sex worker who doesn’t disclose their transgender status is a minefield, and it’s one I have to navigate every day. The trials workers like me face range from navigating transphobic workplaces and colleagues to selling sex to people who would likely not be happy if they knew our truth. I began doing sex… Continue reading Deep In The Shadows: Working Trans Without Disclosure

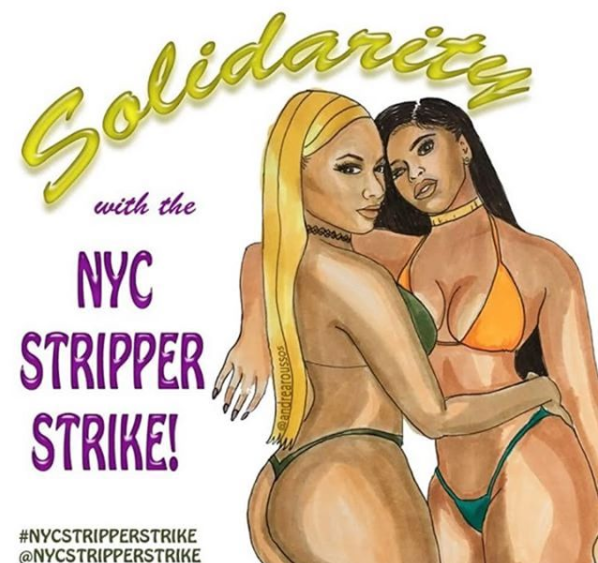

Why The #NYCStripperStrike Is So Relevant And So Long Overdue

A slightly different version of this piece was originally posted on Akynos’ blog, blackheaux, on November 8th A personal history of being a Black stripper It’s about fucking time! That’s all I can say about this stripper strike organizing. I am excited to see more and more gentlemen’s club/exotic dancers taking this business seriously enough… Continue reading Why The #NYCStripperStrike Is So Relevant And So Long Overdue