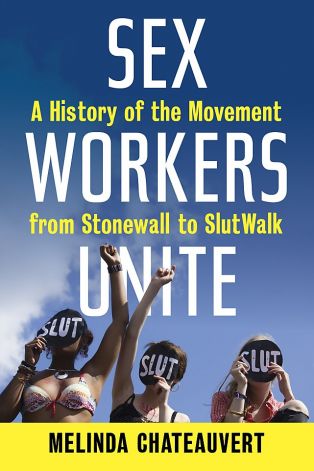

Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk (2014)

Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk, is a pretty damn good history of our movement. Still, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s critique in her review of the book—that male and genderqueer sex workers are given short shrift in Chateauvert’s work—is valid. Glancing references to Kirk Read and HOOK Online aside, the book is a bit of a hen party.

Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk, is a pretty damn good history of our movement. Still, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s critique in her review of the book—that male and genderqueer sex workers are given short shrift in Chateauvert’s work—is valid. Glancing references to Kirk Read and HOOK Online aside, the book is a bit of a hen party.

Then again, so is the movement it chronicles. Sex Workers Unite is a fairly accurate portrayal of our organizing, for better or worse. The index and the footnotes provided me with a comforting sense of familiarity as my eye skimmed over names well known to me, from Carol Leigh to Kate Zen. (Full disclosure: Tits and Sass posts were often cited, including one of my own.) At least, finally, in this text trans women sex workers are given the central role in our story that they’ve played in our activism. The book covers early movement trans heroines like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in depth, documenting their participation in the Stonewall riot and their founding of STAR House, a community program serving queer and trans youth in the sex trades. They were also involved in the lesser known organization GLF (Gay Liberation Front), an anti-capitalist group that “made room for prostitutes and hustlers, including transwomen, straight and lesbian prostitutes, gay-for-pay hustlers and stone butch dyke pimps,” but hilariously enough, couldn’t come to a consensus on whether it was still okay to take money for sex after the revolution. Chateauvert follows this thread of trans history throughout, never failing to highlight trans women sex workers’ contributions to such integral activist projects as Women with a Vision, HIPS, and Washington DC’s Trans Empowerment Project, as well as their more general influence in shaping sex worker culture.

When I first picked up the book and noted the subtitle, I felt a brief pang of disappointment at the fact that our movement is still so little-known that the the two iconic events that bookend Chateauvert’s summation of our chronology in her title—Stonewall and Slutwalk—actually properly belong to other movements. But as I started to read, I was delighted to realize what the author had done by integrating our narrative with that of so many other struggles for social justice, reminding the reader of sex workers’ critical participation in so many movements over the decades. From GLBT/queer rights and feminism to AIDS activism and harm reduction, Sex Workers Unite makes it clear that you can’t really talk about the history of activism in the US without talking about us. The book tackles our invisibility in these integral roles—in its chapter on Stonewall, for example, it highlights the rarely mentioned fact that drug using trans sex workers were the key participants of the riot, and strips the respectability politics from the typical portrayal of Stonewall rioter Rivera, who is often remembered as a trans activist forebear but not so often revered for supporting her activism via street sex work.