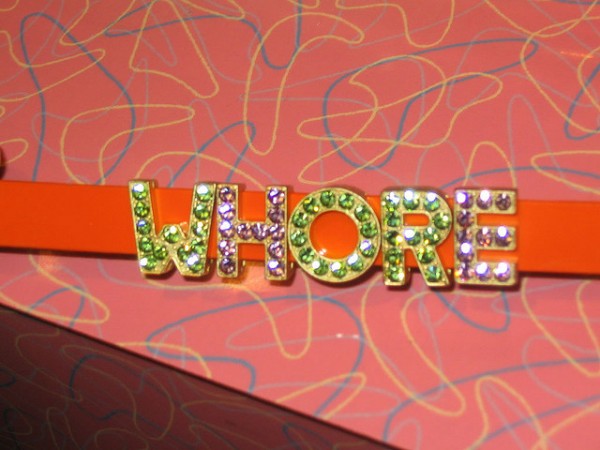

“Whore” Is A Good Place To Start

When I was just a teeny tiny bottle of airplane-ready champagne, I was called a whore by a boy in my middle school science class for having the audacity to own breasts and opinions at the same time,while only being willing to share the latter. Once I got to college, men started to call me a whore in the streets when I refused their advances and they called me one even more loudly when I taught myself not to allow their presence to register on my face. I was called a whore by clients more often when I would refuse certain services, but not when I would provide them willingly. But since you could put a pair of eyeglasses on a calcified ostrich turd and its opinion would have as much gravity as those of boys, strange men, and clients, these words never especially bothered me.

I’ve always been peripherally aware of the importance of reappropriating the language of sex work but never felt I really had skin in the game until I felt how badly “whore” burns from certain tongues and with certain intentions. Since “whore” was thrown around my whole life as shorthand for “woman who does things I don’t like,” I never felt especially connected to it as it related to sex work, even when doing sex work that reflected the most literal understanding of the word. I’ve even been known to say things like, “Um, sex workers are dying out there. Does it really matter what we call ourselves?” I’m aware now that starting a sentence with “um” reflects fluency in Sanctimonious Cunt more than it reflects nuanced understanding of the issues sex workers face. Forgive me, I was an unsophisticated bottle of André at the time, a mere shadow of the Dom Perignon White Gold Jeroboam I am today. But back to being a whore.

In late July, a man who claimed to love me and who had never taken issue with my profession before called me a “whore” to my face. He told others I was a “whore” when he needed to discredit me as quickly and mercilessly as possible. Prior to our falling out, my work in the adult industry had been something that concerned him only when I reported pushed boundaries or feelings of regret and insecurity. He was supportive and sometimes downright titillated, insisting on christening my new work outfits by getting lap dances in them before anyone else did. I happily obliged because I loved him and got to choose my own soundtrack. When things quickly deteriorated and I feared for his new girlfriend, I warned her about malicious and dishonest behaviors of his which I thought she should be aware of.

His first line of defense to her was my work and it was his first line of offense against me. Obviously, he had been driven to threaten me with violence because I was a deranged stripper that thought he loved me; he just had to set me straight. The very idea was ludicrous, loving a sex worker. When he used whore stigma against me, it was to explain why he never wanted monogamy with me and how I had always been just a source of fucked up sex and that all his stated affections had been part of a game designed to entertain himself.