I Did Not Consent To Being Tokenized

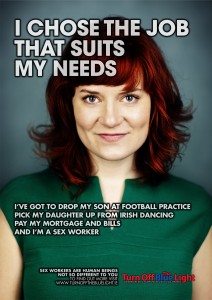

I am a sex worker who was coerced into doing work I felt violated by, and I am horrified by SWERFs (Sex Worker Exclusionary Reactionary Feminists) who insist that all sex work is by nature coerced and non-consensual.

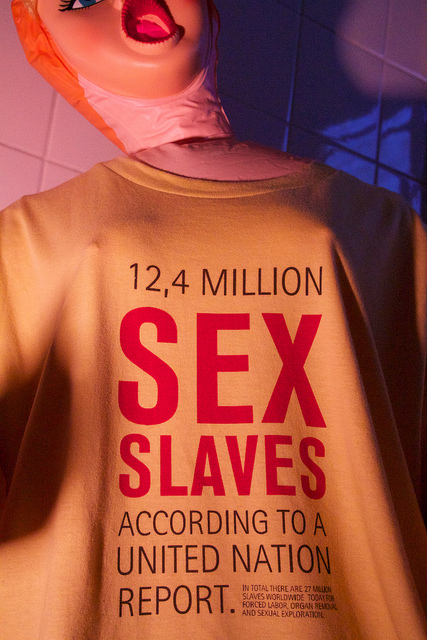

Recently, I’ve noticed a disturbing rise in anti-sex work rhetoric that rests on the premise that all sex work is coerced. The proponents of this claim argue that because the workers may need the money and thus feel unable to turn down a proposition they are uncomfortable with, sex work encounters are always non-consensual. As far as they are concerned, if money is involved, sex can never be consensual. They claim that by promoting the criminalization of all forms of sex work, they are “protecting” sex workers and engaging in “feminist solidarity” with us.

I’ve already seen a number of brilliant sex workers debunking this argument: by discussing their own consensual sex work experiences, by pointing out that all professions involve money and thus a potential for coercion or abuse of workers, and so on. Tits and Sass contributor Red wrote a particularly interesting piece on her tumblr in which she notes that she finds the term “constrained consent” a far more accurate term than “coerced consent.” All of those points are valid and important, if often ignored by the audience they’re intended for.

But I’ve noticed one perspective missing from the discussion: that of someone who was sometimes unable to consent to sex work, and is harmed by those who would tokenize that experience and devalue the experiences of other sex workers. After seeing my experiences casually commandeered by SWERFs as a talking point, I’ve decided to speak up.