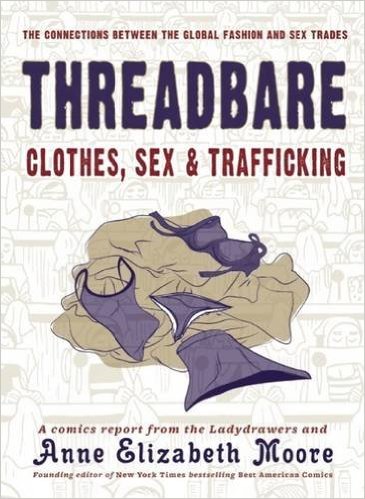

Red: In journalist Anne Elizabeth Moore’s new book Threadbare: Clothes, Sex, And Trafficking, in which years of her reporting are illustrated by comic artists Delia Jean, Melissa Mendes, Ellen Lindner, Simon Haussle, and Leela Corman, among others, she takes us around the world, untangling the many levels of exploitation and corruption inherent in the garment industry.

Red: In journalist Anne Elizabeth Moore’s new book Threadbare: Clothes, Sex, And Trafficking, in which years of her reporting are illustrated by comic artists Delia Jean, Melissa Mendes, Ellen Lindner, Simon Haussle, and Leela Corman, among others, she takes us around the world, untangling the many levels of exploitation and corruption inherent in the garment industry.

Moore takes us way beyond the factories themselves, to shadowy zones I never heard of before reading the book. The garment industry makes use of “Free Trade Zones,” spots on U.S. soil that are exempt from all U.S. rules and regulations, where abuses run rampant.

The author connects all the threads of industrial and imperialist abuses, and presents a seamless and ugly portrait of an imperialism that never died, only changing to better fit the times—an imperialism which is still at the heart of so many exploitations and abuses worldwide. With rope from the garment industry itself, she creates a noose to hang it with. Now we gotta get more people to read the book and spread the word.

Moore interviews retail workers at H&M, a fashion model, former workers and business owners in Austria’s shrinking garment industry, and, most pertinently to us, anti-trafficking NGOs who “rescue” sex workers into the garment industry for a fraction of a living wage. All of it is painfully fascinating, the kind of horrified interest that an especially bad injury might generate, as you read on and realize how deeply all of these facets are intertwined and interdependent.

The garment industry isn’t just implicated in internationally substandard wages for women: it’s one of the root causes of them. The garment industry isn’t just loosely connected to imperialist anti-trafficking NGOs that force women into garment factories: Nike, for example, funds the anti-trafficking org Half the Sky, which is run by Nick Kristof, who not only writes openly in the New York Times about his support for and belief in the necessity of sweatshop labor—he funnels the women rescued by Half the Sky right into garment industry sweatshops which profit the very industries on the board of or funding Half the Sky! And it isn’t Just Half the Sky. Shared Hope International, the local anti-trafficking thorn in my side, has a board member who is also the international HR manager for Columbia Sportswear.

I knew before reading Threadbare that the garment industry profited off the anti-trafficking movement’s “rescue” of sex workers, but I didn’t understand just how inextricably the two were linked. I didn’t understand that it wasn’t just convenient placement and timing—it’s a deliberate, planned strategy to keep wages down and to keep women workers across the world easily exploitable.

Caty: I’m not a huge comics reader, though I’ve definitely gone through some of the classics throughout my reading life, such as Sandman and Watchmen, and on the more literary side I’ve read Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and the like. But as graphic novels get more of a foothold in sex work lit with titles like Rent Girl, The Lengths, and Melody: Story of A Nude Dancer, plus popular sex worker comic artists like Jacq The Stripper and even Tumblr darling brothelgirl, I’ve certainly been reading more comics lately. And there’s begun to be more comics coverage of leftist non-fiction, too—Harvey Pekar’s graphic history of Students for a Democratic Society particularly impressed me. So, now, finally, we have the convergence of these trends with non-fiction sex worker and labor rights comics title Threadbare.

I’m not entirely sure the comics format really works here. The fonts can be punishingly tiny, and there’s just SO much exposition. I got stalled on the book myself for months somewhere in the middle of the section on Austria’s fashion history and only ended up finishing it to write this review. On the other hand, the illustrations are gorgeous, and I’m not sure a short prose book would’ve allowed the dense material to be any more accessible.

Red: I came to comics really late; I’ve always had trouble focusing on pages where multiple things are happening. For me, images accompanying a text don’t make it easier to read, it’s too much! I love comics now, after being won over by Matt Fraction‘s Hawkeye, but reading comics and graphic novels is still a lot of work for me if I’m not using the ComiXology app. Threadbare is definitely worth the work, and many of the artists streamlined their panels in a very clear and accessible way.

I came to this book as someone who already knew a lot about exploitation in the garment industry and exploitation in the culture and running of anti-trafficking NGOs, knowledge I got through constant sifting through a sex work Google alert. People ask me for receipts all the time and I am so profoundly grateful to now have a thoroughly sourced and cited book to hand over to clinch my arguments and temporarily silence the twats.

Caty: I agree that this book should become part of every activist sex workers’ arsenal. It delivers some important perspective about sex workers’ rights as a labor movement by connecting the labor issues of garment industry workers and sex workers—who are so often the same people!

In My Skin by Australian Kate Holden is an example of the “my drug whore hell” memoirs to which I am both attracted and repelled. I’m an IV drug-using sex worker but do not subscribe to the NA model of addiction-as-disease and don’t define my life as hell. Most media doesn’t show anything true about my life at all, but instead falls back on depictions of drug-using sex workers as dead hooker jokes, grotesque caricatures of secondary characters with barely any lines. So I eat up all the tell-alls about them I can find, because even if their perspective on drugs and sex work isn’t mine, someone like me is the main character.

In My Skin by Australian Kate Holden is an example of the “my drug whore hell” memoirs to which I am both attracted and repelled. I’m an IV drug-using sex worker but do not subscribe to the NA model of addiction-as-disease and don’t define my life as hell. Most media doesn’t show anything true about my life at all, but instead falls back on depictions of drug-using sex workers as dead hooker jokes, grotesque caricatures of secondary characters with barely any lines. So I eat up all the tell-alls about them I can find, because even if their perspective on drugs and sex work isn’t mine, someone like me is the main character. Anyone who knows me will tell you I struggle with nuance. Different people have different ways of expressing this: two of my friends describe me as a typical Capricorn, I’ve been called an “angry bumblebee,” “strident,” and “ideologically rigid” by some of my best friends. They aren’t exaggerating! I’m capable of nuance, especially when talking about my own experiences, but when I see good things said about the sex industry without any mention of the bad, my internal alarm starts screeching.

Anyone who knows me will tell you I struggle with nuance. Different people have different ways of expressing this: two of my friends describe me as a typical Capricorn, I’ve been called an “angry bumblebee,” “strident,” and “ideologically rigid” by some of my best friends. They aren’t exaggerating! I’m capable of nuance, especially when talking about my own experiences, but when I see good things said about the sex industry without any mention of the bad, my internal alarm starts screeching.

The search for the supposed

The search for the supposed