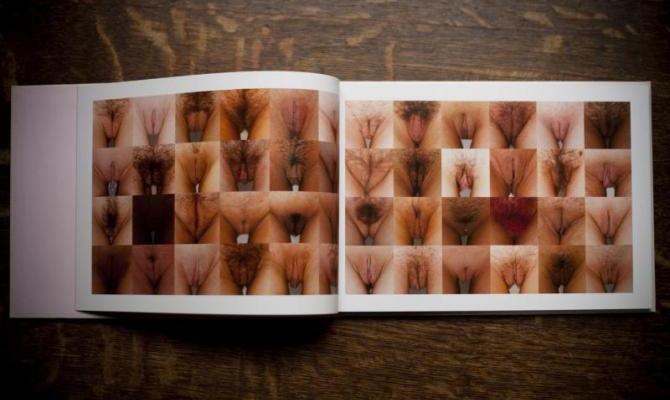

Wrenna Robertson’s I’ll Show You Mine

I’m putting my eyeliner on, but when Diamond, who’s next on stage says, “Hey can I check my shit?” so I move over to give her space at the mirror. She pulls down her panties, she bends over, ass side to the mirror, spreads her cheeks, looks through her legs at the mirror, checks, straightens up, straightens her panties and walks out of the dressing room.

I’m putting my eyeliner on, but when Diamond, who’s next on stage says, “Hey can I check my shit?” so I move over to give her space at the mirror. She pulls down her panties, she bends over, ass side to the mirror, spreads her cheeks, looks through her legs at the mirror, checks, straightens up, straightens her panties and walks out of the dressing room.

If you haven’t guessed, I’m a stripper in an all nude club. Strippers need to “check their shit” because they show their “shit.” Since I see my coworkers’ vaginas on a pretty regular basis, I’ve learned there’s nothing regular about vaginas and I’ve been on a personal mission to convince women of all occupations that their non-regular vaginas are plain normal. Hence, I was thrilled to be getting a book all about vaginal diversity.

Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers.

Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers.