By Caty Simon and Josephine

Ten years ago, the remains of four sex workers — Melissa Barthelemy, Megan Waterman, Maureen Brainard-Barnes and Amber Lynn Overstreet Costello — were found close to Gilgo Beach, near Long Island, New York. The bodies were unearthed after a frantic 911 call from another worker: Shannan Gilbert spent 21 minutes telling a dispatcher a man was trying to kill her, then she disappeared. It became evident that a serial killer was targeting area sex workers he met on Craigslist, so the Suffolk County police commissioner asked the community for help. In response, the local SWOP demanded amnesty for sex workers, a request the police department scoffed at. The case featured multiple suspects — including a former Suffolk County police chief — and remains ongoing.

That case, which came to be known as the Long Island Serial Killer case as it expanded to 10 victims, demonstrated how the internet revolutionized sex work, taking it online and out of the shadows without the help of pimps and traffickers. The public, however, interpreted the case differently; Craigslist made sex-for-money easy and accessible — and dangerous, it was surmised. The notion that the police department had erred couldn’t compete against the lurid narrative of sex workers naively meeting their killers online. Robert Kolker, who wrote a book on the subject, told TAS in 2013 that he was certain that the case might have unfolded differently if the women weren’t sex workers, or “a different class of people” as he put it. Either way, Craigslist’s Adult ads section shuttered soon after, marking the beginning of the end of the internet as a safe haven.

Today is Dec. 17, the annual day we rally to end violence against sex workers, and the last such day in this decade. The environmental changes sex workers have endured are too many to list but, in the day’s spirit of reflection and rememberance, we’re certain it’s paramount to revisit the challenges we’ve faced and the hard work we’ve endured.

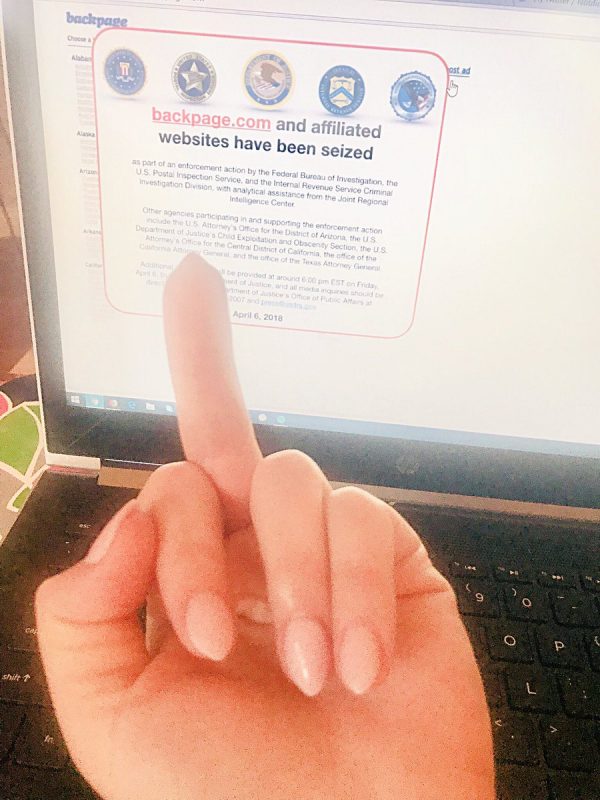

The end of Backpage

David Elms founded The Erotic Review, a hellsite that gave misogynist clients the ability to “review” and exchange intel about workers they deemed scammy, unattractive, or not generous enough with their favors. Elms was arrested in 2010 after he attempted to hire a hitman to murder a worker he had recently doxxed. TER, of course, was created to “protect” clients.

If only politicians had attacked TER with the frenzy that they did Backpage nearly a decade later. (After all, sex workers mostly loathed TER, while Backpage, for all its faults, was an inexpensive, low threshold platform for low-income sex workers to independently advertise for clients.) The precedent was there: MyRedBook and Rentboy had already been shuttered earlier in the decade. SESTA-FOSTA’s passage had ushered in a wave of preemptive site closures by ad platforms unwilling to risk the civil and criminal liability they now faced, though the Department of Justice wouldn’t end up needing the new law when it did pounce on Backpage.

Backpage was an impressive bust. The site was launched in 2004 by two former alt-weekly editors who sought to mimic the ad model that funded their old paper. It sat in the crosshairs of legislators like Kamala Harris, who bombastically declared it a hub of child sex trafficking. (Senator Harris played a major part in the crusade against Backpage in her previous role as California Attorney General, as well, filing multiple sets of charges against Lacey and Larkin even when pre-SESTA-FOSTA courts repeatedly shut her down.) Workers felt unsurprised when it was seized by the FBI in a dramatic, public spectacle. Regular users of the site recognized the writing on the wall earlier, as using it became an unnavigable hell, thanks to the shut down of the Adult Services section and the growing need to pay using cryptocurrency.

Only the founders, it seems, missed the signs. Michael Lacey and Jim Larkin made millions off the enterprise, declaring it a paean to free speech. “What they are essentially arguing is for is the First Amendment right to profit off a criminalized group of people,” Caty Simon reflected after its seizure. In fact, it wasn’t until their business began to crumble that they attached themselves to the sex workers’ rights movement. Never, though, did Lacey and Larkin suggest that, perhaps, none of the services available on the website should be criminalized.

For all the indictments piled on Lacey and Larkin, it was us sex workers who suffered from the Backpage seizure. After that disastrous spring of 2018, with SESTA-FOSTA’s passage at the end of March swiftly followed by the DOJ’s takedown of Backpage in the beginning of April, both the national and international sex trade would never be the same. Both outreach workers and police officers reported street sex worker populations quadrupling or quintupling in many major American cities as indoor workers were displaced. We do not have much hard data on the harms sex workers have suffered since, but the general consensus is that people have died and suffered in large numbers, and that most markets have not recovered from this double blow.

Strippers, welcome to the movement

By 2019, strippers cemented themselves in the canon of pop culture. This process gained traction in 2012 when Rihanna offered the ultimate endorsement with the release of the song “Pour It Up.” She subverted the classic media trope of strippers-as-props and made herself, as the star of the song (and the video), into one. As the decade progressed, ex-strippers became more numerous in the mainstream: Blac Chyna became a Kardashian; Kash Doll went viral; Amber Rose sponsored the Slut Walk; Jacq the Stripper consulted for the film “Hustlers”; Cardi B is the president.

Strippers, of course, are fiercely independent, a result of working in the closed economy of a strip club. The rise of social media broke down those walls, at least a bit. Where once, conversations about work were only on Stripperweb, by the middle of the decade many had migrated to Twitter, Instagram, and ultra-exclusive Facebook groups. These new forums allowed strippers to integrate into the larger sex worker community.

It was just in time, too, as strip clubs became targets of of law enforcement’s newfound fixation on indoor workers. BARE-NOLA campaigned tirelessly to highlight this while they publicly fought law enforcement for closing their clubs, displacing scores of workers. Lindsey of BARE issued a warning: “Beware of a man called Scott Bergthold. He’s swiftly and effectively shut down adult businesses around the country using laws that are already on the books.”

Bergthold, an attorney and darling of the Christian right, spent the decade going from municipality to municipality using bogus secondary-effects research to convince legislators of the harms of adult businesses like strip clubs, massage parlors and porn stores. He then crafted litigation-proof laws to regulate those businesses — in many cases, regulating them right out of business. His ordinances exposed indoor workers to warrantless raids, increased surveillance, and invasive registries.

Of course, even as clubs were under attack from the outside, the stresses on the inside began to draw attention. Namely: They can be really shitty places to work. Class-action suits against strip clubs piled up, almost all of them alleging employee misclassification, almost all of them successful. Déjà Vu, faced with losing a case to three Jane Does in 2017, settled for just over $6 million dollars. That same year Gizelle Marie kickstarted the #NYCstripperstrike, a movement that began a national dialogue about institutional racism and colorism. In California, the state’s Supreme Court decision on the Dynamex case radically altered how businesses are able to classify employees, instantly morphing every stripper in the state into an employee instead of an independent contractor — with mixed results. In response, a small group of strippers decided it was time to form a union.

Get out of the way, Stormy Daniels

Stormy Daniels intersected with both of those issues — labor and the law — in very public ways. She emerged as an unofficial representative of sex workers in 2018 when she publicly challenged Donald Trump in court over hush money his attorney, Michael Cohen, paid her during his campaign. Sex workers, at this point, had been working for decades toward the kind of visibility and legitimacy that Daniels commanded immediately. And sex workers, for decades, have been a part of a long tradition of abruptly destroying politicians’ careers with scandalous affairs.

Juniper Fitzgerald coined the term the “Stormy Daniels Effect”, writing: “The ruinous nature of sex workers is in the secrets we unveil about society — namely, that all human interaction has a price under capitalism. By acknowledging that sex work is not inherently revolutionary, we help dismantle the racist, sexist, ableist, classist, imperialist systems that commodify every aspect of our lives.”

With Trump, the stakes were different: Daniels became an instant folk hero, but at almost any other time in history, her accusations would’ve been readily dismissed.

Daniels didn’t utter the term “sex worker” until 2018, when she did a video for XBiz that was more of a client-facing promotional video than actual activism. But she has tepidly dipped her toes in organizing. Sort of. In 2010, she announced that she would unseat Sen. David Vitter in Louisiana on a platform of legalizing prostitution. Several years later, she was arrested during a phony trafficking sting at a strip club in Columbus, Ohio, for violating laws that — yup — Scott Bergthold wrote. After Dynamex, she anointed herself the unofficial spokesperson for the state’s strippers — she wrote an op-ed and staged a protest in Sacramento, absurdly arguing that strippers should be exempt from federal labor law. Daniels failed to disclose that she worked as a spokesperson for Déjà Vu, the largest chain of strip clubs in the state.

Porn workers navigating the tech economy

Porn workers navigating the tech economy

Daniels could have lent her platform to help the workers in the industry that made her famous: porn. The 2010s made the porn industry brutally competitive as tube sites like PornHub made content endlessly accessible and painfully free. Kayden Kross and Stoya attempted to break that model in 2015, founding TrenchcoatX: “The performer-run and owned site is powered by the vision of its two partners and stands in stark opposition to the search-optimized tube sites that are closing in on monopolizing porn distribution.” It functioned for almost five years; they sold it in January 2019.

PornHub survived the 2010s by strategically normalizing the consumption of pornography with their quirky PR stunts: Their tactics included grabbing free publicity with a rejected SuperBowl ad, offering to plow snow after a blizzard in Boston and pledging to send a worker to space. Journalists eagerly devoured the narrative that PornHub was a different type of business. The fact that PornHub wouldn’t exist without pirated labor? Crickets. “More than people not understanding it’s stolen labor, people don’t see porn as legitimate labor or having value,” fetish model Lux Lives explained, “in part because tube sites and piracy have cheapened it but also due to whorephobia.”

The conditions of the workers making porn drew little attention — unless those conditions were exposed via a titillating documentary. Enter “Hot Girls Wanted” and “Hot Girls Wanted: Turned On,” both produced by Rashida Jones. These exposés were met with intense scrutiny from workers in the industry, calling it demeaning and exploitative. Gia Paige felt so upset that she pulled out of participating in the series — which didn’t stop the producers from citing “fair use” for borrowing her footage and exposing her legal identity.

Government bodies had their own unformed ideas about the conditions porn workers endured. AB-1576 almost radically criminalized the choice porn performers were able to make by mandating condom usage on sets in California. And a side effect of the Obama-era Operation Chokepoint resulted in the mass closure of porn workers’ bank accounts.

Law enforcement and anti-traffickers: They still suck

On Dec. 10, 2015, an ex-college football player who had fallen just short of the NFL unraveled, on live television, into hysterical sobs as a judge read his convictions — 18 of 36 charges, including first and second-degree rape, carrying a sentence of the rest of his life in prison. That was a nation’s introduction to Daniel Holtzclaw, who leveraged his size and strength into a job with the Oklahoma City Police Department and then spent a good portion of his career serially raping Black women, including drug users and outdooor sex workers. Feminist organizations were eerily silent after Holtzclaw’s arrest. It was Black sex workers, in concert with Black Lives Matter, that forced the media to pay attention.

That’s just one example. Anybody with a passing interest in the issues sex workers face must examine the sickness that permeates law enforcement. Sex workers nearly universally report being scared of and victimized by cops, in situations including (but certainly not limited to): Strippers entrapped in screwball raids, massage workers surveilled thanks to the Patriot Act, trans women profiled and unlawfully arrested and law enforcement themselves acting as traffickers. It’s such a simple concept: Criminalization endangers sex workers, in large part because of the threat from cops.

This fuels the sick delusions of the anti-trafficking industry. We’re using the term industry intentionally here, because that’s what it is. Anti-traffickers are parasites of the sex work industry, gobbling up funding, prestige, and fame while accomplishing nothing of import. This industry has systematically threatened the safe harbor of sex workers quite intentionally, gleefully using federal grant money to fuel bogus stings which purport to “rescue” sex workers from the clutches of their pimps.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Nicholas Kristof rabidly elevated the status of such raid-and-rescue operations when he, traveling with an elegant anti-trafficker named Somaly Mam, covered a violent raid on a Cambodian brothel — and live-tweeted the entire event. He wrote: “That’s how the battle against human trafficking is being fought around the world. Ultimately, the way to end this scourge is to make it less profitable and more risky for the traffickers.” Mam, who Kristof described as his hero, was later publicly discredited after it was revealed she fabricated testimony to the U.N. General Assembly, as well as much of her memoir.

During the 2010s, we were led to believe sex trafficking was everywhere. Cindy McCain declared the Super Bowl the largest human trafficking event in the country. (Debunked.) Outfits like the Polaris Project and Demand Abolition presented murky data, asserting the average age of entrance into sex work is 12-14 years old. (Debunked.) Sex trafficking was apparently so prevelant you could get kidnapped by traffickers right out of an IKEA parking lot. (Debunked.)

Kristof was logically correct — making trafficking less profitable would curb it. But his approach? Incorrect and illogical. The only way to curb trafficking is improve sex workers’ safety. Safety, logically, comes from security. And security, logically, comes from resources. Resources, logically, are things like housing, food, and money. The JVTA was passed near unanimously in 2015 — but it did not allocate resources for trafficking victims, instead funneling resources toward special prosecutors, wiretap initiatives and training for military veterans to “rescue” victims. Likewise, SESTA-FOSTA was passed nearly unanimously three years later. It too, did not allocate resources for victims; instead it chipped away at mechanisms sex workers require to stay safe while they work. This is the most predictable pattern around anti-trafficking measures: The resources for publicity and detection are always available; resources for victims themselves are virtually non-existent.

Today is a fitting day to acknowledge the resourcefulness of sex workers themselves. Nobody has worked harder to prevent trafficking than this very community. We’ve made space for workers that survived as well as workers that did not. We’ve workshopped around bad laws and rallied for those punished under those laws.

We’re changing the narrative.

There’s momentum

If the aughts were the decade of sex positivity and middle class sex worker activism, this decade increasingly saw a movement led by marginalized sex workers, centered around the ethos of grassroots organizing, sex-worker-led outreach, and mutual aid.

A look at organizations around the country right now demonstrates this trend—GLITS in New York City offers mutual aid to trans sex workers of color. Red Canary Song, founded upon Chinese migrant sex worker Yang Song’s death in a massage parlor sting under suspicious circumstances, focuses on the concerns of Chinese massage parlor workers in Queens. In Massachusetts, Whose Corner Is It Anyway provides harm reduction, mutual aid, and leadership capacity development by and for injection-drug-using and/or housing insecure low-income sex workers. (Full disclosure: Caty is a founding co-organizer.) Meanwhile, Chicago and New York based Support Ho(s)e includes incarcerated Black sex worker Alisha Walker as a collective member and leader.

Maybe elder sex worker activist Carol Leigh was prescient when she told TAS in 2013, “We need to learn how to develop past the 70s movement based on middle class feminism/queer activism to a movement that is based in the representation and leadership of sex workers from all communities, strata, and circumstances. Maybe after years of feminism and other movements that were largely dissociated from issues of class and race, things will shift.”

In the beginning of this decade, TAS documented the alienation of drug-using sex workers whose experiences were swept under the rug by the movement, in a chorus of a thousand sex worker microcelebrities chanting “I’m not some crackhead working the street” in interviews. Now, however, the movement has a vital connection to harm reduction. Outreach teams like Seattle’s Greenlight Project of POCSWOP do harm reduction supply distribution designed for sex workers by sex workers. We Are Dancers does the delicate work of such outreach in Chicago strip clubs. National sex worker rights organization SWOP-USA now even funds a needle exchange grant for sex-worker-led groups.

In 2017, when Backpage closed down its Adult Services ad section, in the midst of the economic panic before we all migrated to the dating section for the rest of the site’s tenure, sex workers created collective funds to help those of us hit hardest when no one else would. One of these funds, Lysistrata, survives to this day. It created a collective of majority Black sex worker core members, offering emergency micro grants to sex workers all over the US. Lysistrata led the way forward towards a grassroots sex worker movement which no longer siloed direct services and organizing. Other organizations like Support Ho(s)e now also offer emergency funds, and regional collective funds like SWEET (Sex Workers Emergency Endowment of Tucson) have cropped up. We’re finally recognizing that in order for organizing to be accessible to anyone but the privileged few, the same movement which does activism must also provide resources.

And as the tenor of the movement changes, so do our chances for success. In 2008, for example, Proposition K, to decriminalize sex work and offer sex workers immunity as victims of violent crime in San Francisco, got a 59 percent no vote on the ballot despite a concerted sex worker campaign.

On the eve of Obama’s election, in the most sex worker friendly city in the country, that was the best we could do at the time.

This year, though, in October, the Washington D.C. city council floated legislation that would decriminalize sex work within the city. Hours upon hours of public testimony followed — deranged anti-traffickers on one side facing off against SWAC coalition reps, a group mostly made up of trans workers of color and led by HIPS advocacy fellow Tamika Spellman—ensued. The council backed down, reneging putting the legislation up for a vote. On the surface, this was a failure—not of the movement, but of the usual legislative sort, with politicians terrified to acknowledge the existence of sex workers. But that first step may have started a machine that can’t be stopped—powerful decriminalization outfits have also popped up in Oregon, Massachusetts, and New York.

And we’ve succeeded in pushing the idea of decriminalization into the mainstream to the extent that in November, newly elected San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin simply announced that his office will not prosecute sex workers. Last week, Harris County D.A. candidate Auda Jones said that if elected, she will follow a similar policy. Moreover, sex work decriminalization has become part of the belief system of the intersectional left—for example, decriminalization of both drugs and sex work has been part of the Black Lives Matter national platform for some years now.

October also featured another step forward: Ayanna Pressley presented a comprehensive criminal justice resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives: The People’s Justice Guarantee, which would end cash bail, solitary confinement and the death penalty. Also tucked inside: A clause calling for the decriminalization of sex work. “Sex work is work,” she told the Huffington Post. “In fact, sex work is often the only form of work for certain marginalized communities who are most vulnerable to housing and employment discrimination.”

And today on #IDEVASW, the largest leap forward of all.

As recently as October 2016, in a TAS review of Chi Adanno Mgbako’s To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism In Africa, we wrote, “…South African deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa made a historic announcement of a nationwide scheme to prevent and treat HIV among sex workers, proclaiming, ‘we cannot deny the humanity and inalienable rights of people who engage in sex work.’…It’s impossible to imagine a U.S. politician of any importance saying something similar.”

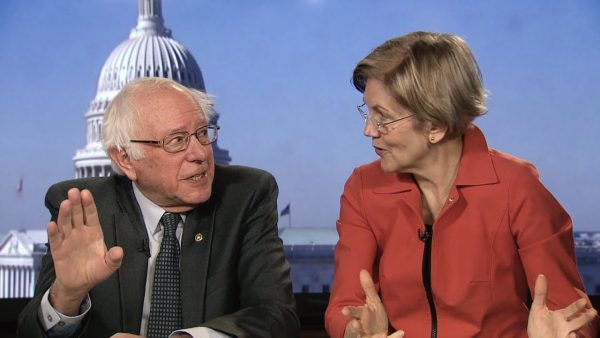

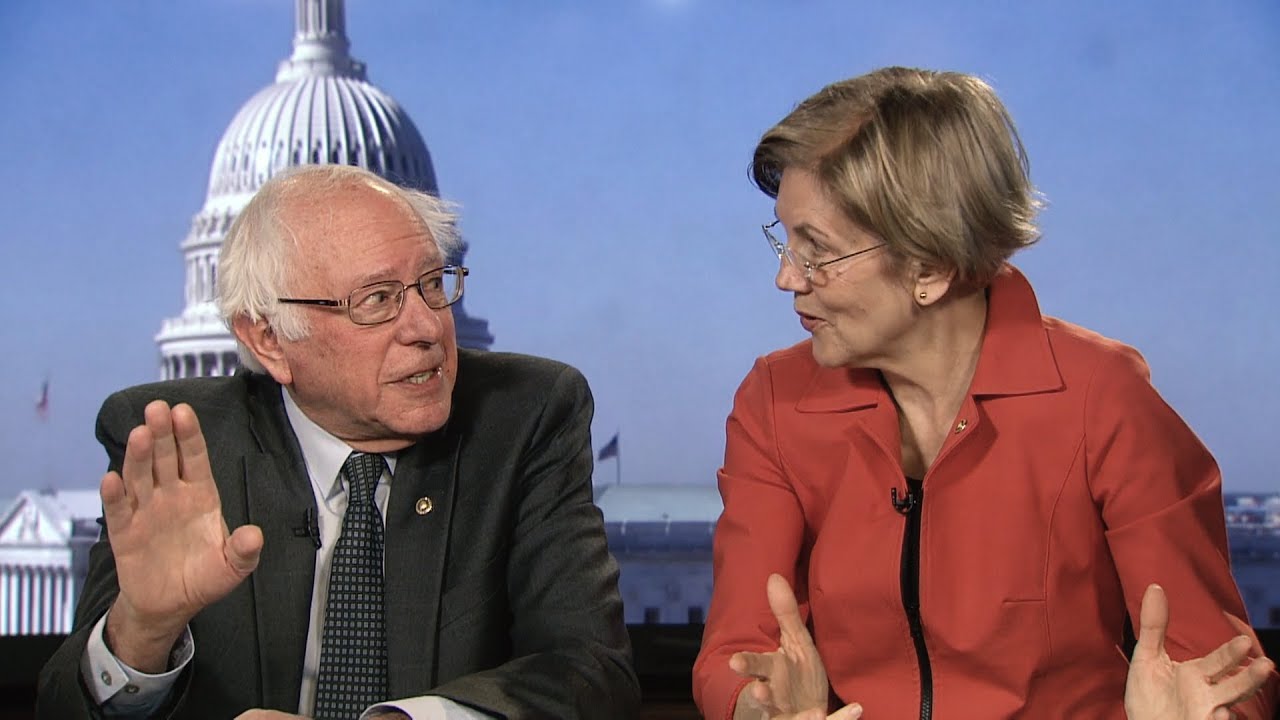

Today, we welcomed the news that presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren was introducing the SESTA-FOSTA Examination of Secondary Effects for Sex Workers Study Act or the SAFE Sex Workers Study Act—a bill mandating that the US Department of Health and Human Services study the effects of SESTA/FOSTA on free speech and sex worker safety–to the Senate. Another presidential candidate, Senator Bernie Sanders, is an original sponsor of the bill. Representative Ro Khanna, who co-wrote the legislation with sex worker activists, and Rep. Barbara Wyden are introducing the bill in the House.

Two presidential candidates are supporting a bill co-written by sex workers from organizations like Reframe Health and Justice and HIPS, a bill which presents sex workers as constituents who must be protected rather than as criminals or agencyless victims.

Of course, we mustn’t think we’re emerging into a utopian future just yet. Warren originally co-sponsored the End Banking For Human Traffickers Act of 2018 with Marco Rubio, of all strange bedfellows—a bill which is threatening sex workers’ bank accounts again in its newest reincarnation as the End Banking For Human Traffickers Act of 2019 after having passed the House Foreign Affairs committee this spring. And she sounded damnedly lukewarm in her public statement on the Safe Sex Workers Study Act today: “As lawmakers, we are responsible for examining unintended consequences of all legislation, and that includes any impact SESTA-FOSTA may have had on the ability of sex workers to protect themselves from physical or financial abuse.”

And of course, Warren and Sanders both voted for SESTA/FOSTA in the first place.

The anecdotal reports Tits and Sass recorded for just the 8 days directly after Backpage went down, a few weeks after SESTA/FOSTA passed, counted 13 sex workers missing and two found dead. Who knows what death toll this study will reveal has accumulated since? The responses to a survey taken by sex worker tech collective Hacking/Hustling, which they presented at a November event at Harvard Law School, depict a devastated sex worker community.

On the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers, we must recognize that this movement has a body count. We can’t keep subscribing to the oblivious middle class outlook we maintained in the aughts. For every Stormy Daniels, a sex worker languishes behind bars. For every Stoya, a sex worker’s bank account is seized. For every sex worker “rescued” by law enforcement, another’s murder remains unsolved.

But we’ve also established momentum. The same post SESTA/FOSTA Hacking/Hustling survey which presented such a bleak picture of our community a year and a half later also revealed that movement engagement has risen by 55 percent since the legislative package passed. This is a movement with legs. As we shift into the next decade, it’s only going to get stronger.

What a comprehensive, well written, informative article. Thankyou

Wow very impressive. I have been a sex worker for 32 years in Texas .. The Struggle is Real but its feeling so much better these days … Thank You for everything your doing for the beautiful ladies and myself in the business , its very contagious so lets keep it up ❤