by Jackie and Alex Jackie’s story, like that of so many, begins with domestic violence, violence she weathers with the help of her sex work. Her son’s father continuously uses abusive financial tactics, severing any ability she’s ever had to gain ground in her life. Her ten-year-long saga has kept her working under the table,… Continue reading Holy Shit: Adventures In Survival Sex Work And Stimulus Checks

Category: Politics

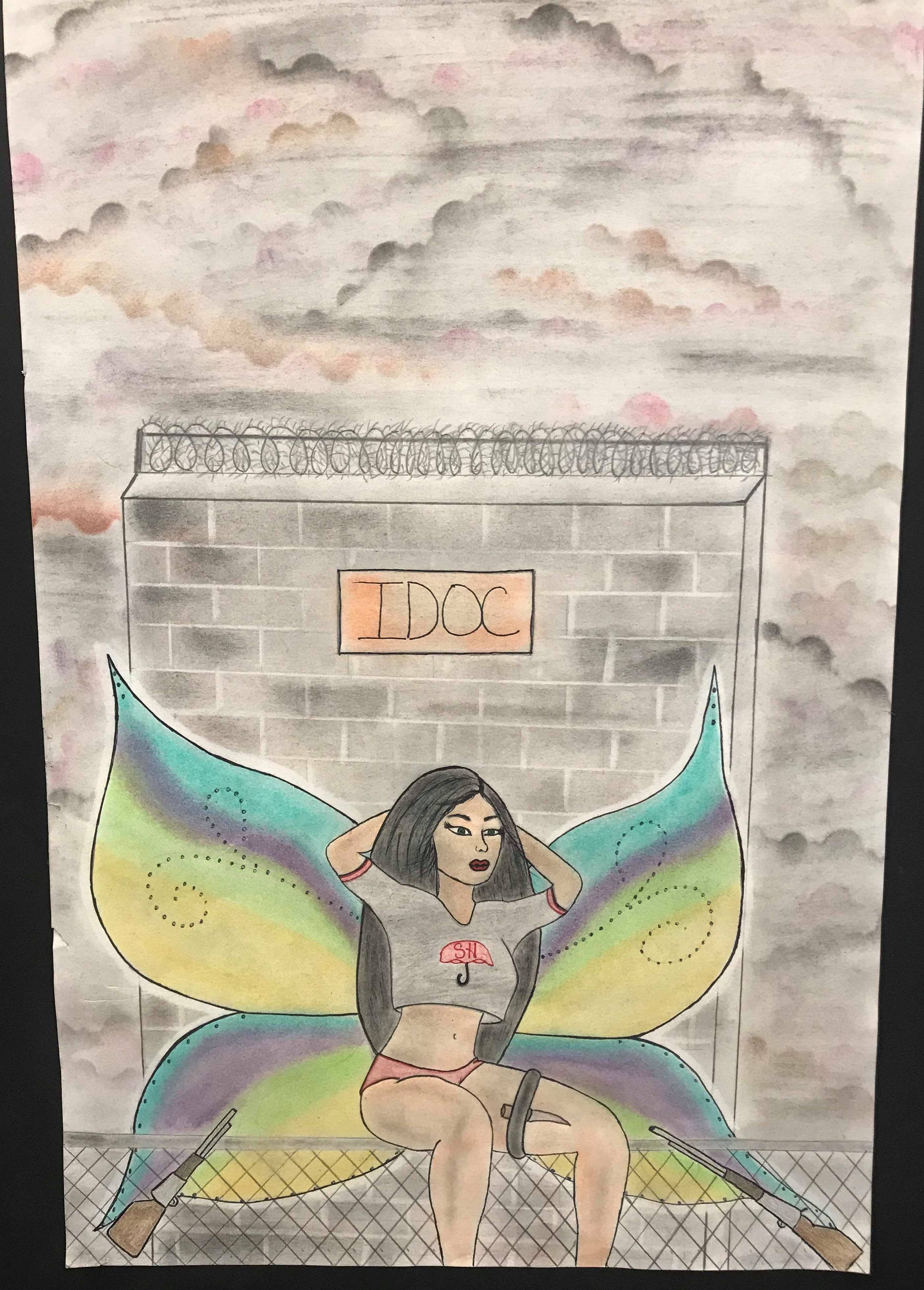

“If U Only Knew How They Were Really Doing Us”: Inside/Outside Communication During A Pandemic

by Alisha Walker and Red Schulte (written by Red, with editing and considerable input from Alisha) Alisha Walker is a 27-year-old former sex working person originally from Akron, Ohio. She was criminalized for an act of self-defense when a regular client threatened her life and the life of a fellow worker in January 2014. A… Continue reading “If U Only Knew How They Were Really Doing Us”: Inside/Outside Communication During A Pandemic

Gender Critical Feminism is Fascism

Meghan Murphy, a Canadian feminist writer who has spent at least five years on this site waging misogynist harassment campaigns against sex workers and trans women, as if it were all she had for a content strategy… is finally suspended. pic.twitter.com/lo9sW9niv8 — Melissa Gira Grant (@melissagira) November 24, 2018 Meghan Murphy was booted from… Continue reading Gender Critical Feminism is Fascism

Sex Working While Jewish In America

We are witnessing the blossoming of a white nationalist nation. Being the person that I am is not easy in the United States right now. It’s not easy for my friends, my family, or millions of Black people, Jews, and LGBTQI people. I’m an Iranian, Tunisian, French and Jewish sex worker. I immigrated from France… Continue reading Sex Working While Jewish In America

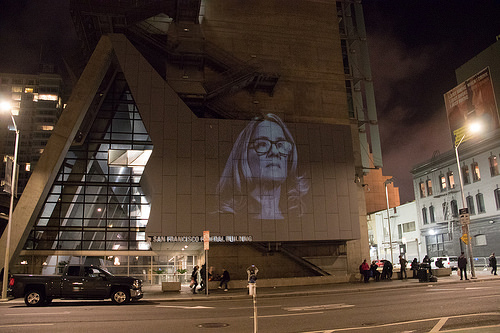

Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Will Kill Disabled Sex Workers Like Me

A few years back, I woke up, looked at my arm, and thought I was in a nightmare. My arms were covered in rashes of tattoo-dark blood blisters so thick my skin looked burgundy-purple from a distance, and bruises, the flesh so swollen it looked like I had been in a car wreck. I had… Continue reading Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Will Kill Disabled Sex Workers Like Me