As we gathered on the busy street corner in front of the Queens Public Library in Flushing on Friday March 29th, over one hundred community members heard our cry: “性工作是真工作!” Sex work is work! The police had blockaded Red Canary Song members from the library steps, protecting the carceral narratives that were being pushed inside… Continue reading The Massage Parlor Means Survival Here: Red Canary Song On Robert Kraft

Category: Trafficking

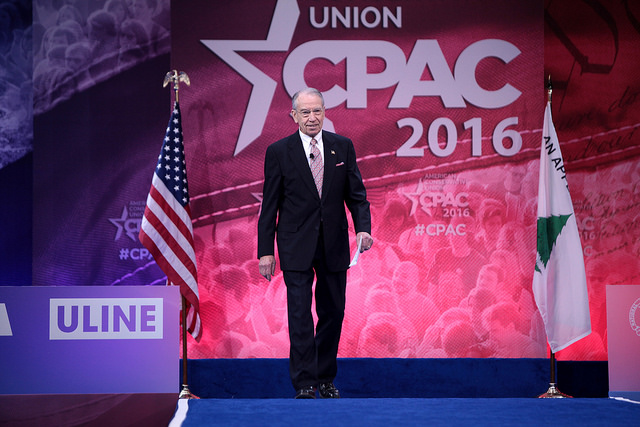

SESTA’s Growing Threat To The Sex Worker Internet

You can always count on a corporation to look out for its own interests. An existential threat to their business model will even trump the good PR that comes from beating on everyone’s favorite marginalized punching bags, sex workers). So, until recently, major tech companies like Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, and Google opposed SESTA,the Stop Enabling… Continue reading SESTA’s Growing Threat To The Sex Worker Internet

Thinking About Cyntoia And My Black Body

Content warning: this piece contains accounts of child sexual abuse and violence against a sex working minor as well as discussion of structural violence. I spent my teen years selling sex on the internet. I grew up on the Craigslist Erotic Services section, finding men who would pay me for something I didn’t take seriously… Continue reading Thinking About Cyntoia And My Black Body

Cyntoia Brown and the Commodification of the Good Victim

Imagine at the age of 16 being sex trafficked by a pimp named “cut-throat.” After days of being repeatedly drugged and raped by different men, you were purchased by a 43-year-old child predator who took you to his home to use you for sex. You end up finding enough courage to fight back and shoot… Continue reading Cyntoia Brown and the Commodification of the Good Victim

What Sex Workers Need To Know About This Month’s Anti-Trafficking Bills

As yet another terrifying resurrection of the zombie Republican health care cut bill looms over the nation, sex workers have their own nightmare legislative threat to deal with this month. That’s because, in the midst of this year’s iteration of commemorative 9/11 pomp, two anti-trafficking bills passed unanimously in the Senate which would vastly expand… Continue reading What Sex Workers Need To Know About This Month’s Anti-Trafficking Bills