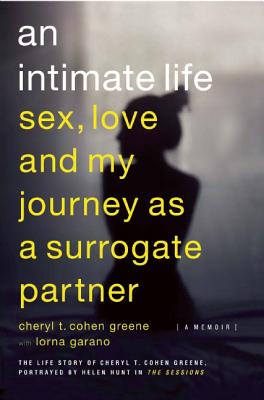

An Intimate Life: Sex, Love, and My Journey As A Surrogate Partner (2013)

An Intimate Life might not exist if not for The Sessions, last year’s Oscar-nominated film fictionalizing the experience of sex surrogate Cheryl Cohen Greene and her client Mark O’Brien. From the blurbs by actors Helen Hunt and John Hawkes to the book’s pictures of Cohen Greene posing next to the stars, it’s obvious the publishers were guessing most readers would come to the memoir through the movie. I hope it finds a wider audience than that, though, because it could have a big impact on the lives of the sexually misinformed, anxious, and ashamed. Through a combination of vignettes about several of her clients and the recounting of her own sexual awakenings, Cohen Greene offers a blue print on expanding one’s sexual life. As one reviewer on Amazon wrote, “Thank you from my heart and penis.” Sounds like something one of my guys would say.

An Intimate Life might not exist if not for The Sessions, last year’s Oscar-nominated film fictionalizing the experience of sex surrogate Cheryl Cohen Greene and her client Mark O’Brien. From the blurbs by actors Helen Hunt and John Hawkes to the book’s pictures of Cohen Greene posing next to the stars, it’s obvious the publishers were guessing most readers would come to the memoir through the movie. I hope it finds a wider audience than that, though, because it could have a big impact on the lives of the sexually misinformed, anxious, and ashamed. Through a combination of vignettes about several of her clients and the recounting of her own sexual awakenings, Cohen Greene offers a blue print on expanding one’s sexual life. As one reviewer on Amazon wrote, “Thank you from my heart and penis.” Sounds like something one of my guys would say.

Awesomely, Cohen Greene opens the book with her number of sexual partners (900) but perhaps less awesomely, she follows that immediately with an explanation of why she’s not a prostitute. I admit that I’m probably a little oversensitive to this, but what is she trying to say exactly? Does she think there’s something wrong with being a prostitute? You don’t come around these parts blowing that horn, Madam. While I imagine Cohen Greene is not someone who would sneer at or shame prostitutes, it’s a little suspicious that she so regularly wants to distance herself from us. For her, the difference in our work is “significant”:

- prostitution is the world’s oldest profession, while surrogacy is new

- intercourse is not the majority or totality of the interaction

- her ultimate aim is to “model a healthy intimate relationship”

- she’s focused on resolving problems and achieving goals rather than simply providing a sexual experience

Her favorite metaphor is that going to see a prostitute is like going to a restaurant but going to see a surrogate is like attending culinary school, the implication being that prostitutes don’t teach their clients anything.

Part of me gets it. But another part of me thinks she might not know many escorts.