In the midst of Girls Gone Wild culture, in which stripping is made to seem effortless and women’s naked bodies are cast as easily replaceable, Kim Price-Glynn enters the Lion’s Den. The Den, a seedy strip club in a small, white, working-class town in the Northeast, is a far cry from the glamorous media images of low lights, glamorous makeup, and dazzling stage sets. Quite the contrary, the Den’s physical layout—run-down and in serious need of repair—mirrors the niche its strippers occupy as the exploited and expendable employees of a club centered around male desire and profit.

In the midst of Girls Gone Wild culture, in which stripping is made to seem effortless and women’s naked bodies are cast as easily replaceable, Kim Price-Glynn enters the Lion’s Den. The Den, a seedy strip club in a small, white, working-class town in the Northeast, is a far cry from the glamorous media images of low lights, glamorous makeup, and dazzling stage sets. Quite the contrary, the Den’s physical layout—run-down and in serious need of repair—mirrors the niche its strippers occupy as the exploited and expendable employees of a club centered around male desire and profit.

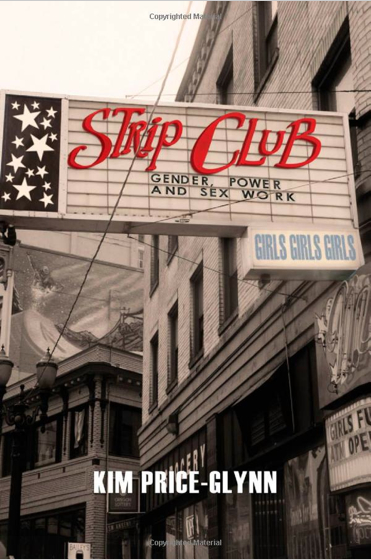

Strip Club: Gender, Power, and Sex Work is an ethnography by Price-Glynn in which she explores what she calls the “gendered processes” underlying the organizational structure at a strip club. While working as a cocktail waitress, Price-Glynn turned her attention to the formal and informal processes by which strip club employees, dancers, and customers exercised authority and had their needs and desires fulfilled. Who “wins” when it comes to stripping? Her answer, while attentive to the ambiguities, suggests that males—customers and employees—“win.” Strippers get the short end of the stick.

Price-Glynn doesn’t believe that strip clubs need to be shut down, nor that strippers are caught in cycles of abuse. Instead, she places the “blame” for the exploitative conditions experienced by Lion’s Den dancers on a larger culture of misogyny. Rape culture, the permissibility of violence, and the unique intersection in the club of racism, ageism, and sizeism are overarching social realities that converge to enable the Den’s brand of sexist exploitation.

Her major argument relates to what she calls “gendered organizational theory.” She reveals the ways in which the club’s formal processes cultivate an environment where male roles allow authority and influence and female (specifically, strippers’) roles are devalued. Price-Glynn considers this “internal logic” of the club contradictory. She describes, in great detail, the division of labor of the club. DJs pick music and receive tip outs from dancers. Bouncers supervise private dances. Customers enjoy a venue to express a certain type of masculinity. Managers describe their job as “babysitting a bunch of 18-year-olds.” The formal structure of the club leaves the women with little influence over its workings. While housemoms and cocktail waitresses have some authority (namely, over dancers), strippers are the only ones who do not formally oversee anyone else’s work. The Lion’s Den, she suggests, is a male-centered and male-serving institution.

Price-Glynn considers this gendered organization contradictory. Strippers often earn much more money than men and women in comparable jobs, but this relatively high income is tempered by the institutional disempowerment they face. As she says, “devaluation of strippers by their male coworkers levels the social playing field, enabling men to save face despite their lower earnings” (65). Strippers experience a sense of liminality regarding their level of power and influence at work. Price-Glynn considers this a simultaneous source of empowerment and disempowerment, and it is this ambiguity that is exploited by male coworkers. “In an industry known for paying women more than the average wage in similar jobs, owners and managers were able to leverage this fact to chip away at the strippers’ incomes.”

In service work, there are three types of emotional labor. The first is a role in which personality and the product are inherently intertwined, as in teaching. The second is when personality is added on to the product or service being provided, like the work of flight attendants. The third is when personality enhances the product or service being sold, as is the case with salespeople. Through her descriptions, Price-Glynn suggests that strippers are all of the above, so ultimately they are ‘hyper-service’ workers.

In spite of this exploitative structure, Price-Glynn concludes that strippers are badasses or, as she puts it, a “force to be reckoned with” (138). Dealing with daily stigmatization, verbal abuse or insults, infantilization at work, and economic exploitation makes strippers tough bitches. It’s the saving grace of an otherwise disheartening book about sexism and labor exploitation. Without this celebratory nod, strippers are powerless to act upon their work environment, forced to keep their work a secret from loved ones, providing draining emotional labor, and habitually performing often-painful cleansing rituals after every shift to “wash the stripper off themselves.”

This is not to say that Price-Glynn’s account is inaccurate. Her attentiveness to the organizational processes at strip clubs is a new take on an old question: What is the experience of power and agency among exotic dancers? By virtue of race, class, reliability, loyalty to the club, or income, some dancers can exercise tremendous influence over others at the club. All dancers know some girls get away with showing up late, missing a stage set, or violating scheduling rules, while other girls might get fired for taking a day off for a death in the family. What governs these actions is a careful calibration of various factors of privilege.

I, for instance, have been uniquely situated as the “only” South Asian woman—often the only Asian woman—at every club I’ve worked at. I’ve also been regarded as the girl who rarely drinks and who studies in the dressing room. Because of the value accorded to these perceptions, I’ve never been “yelled at” by the housemom or management. I’ve been exempt from many of the same rules that all the other dancers at the club must obey. On the flipside, many of the African American women—especially darker-skinned ones—have the opposite experience. Because of their race and relative lack of privilege, they experience the “replaceability” described in the book, a relative lack of influence on their role in the club. Since race only warrants a bracketed discussion in this book because the Lion’s Den is largely a “white” space with limited and marginal space for people of color, this important nuance is overlooked.

While dancers and sex workers may find the descriptive depth of the book cumbersome, this book is a great introductory read about stripping for readers of all stripes. Price-Glynn summarizes major debates in the sex worker literature, including an accessible overview of radical feminism and Marxism in relation to her topic. For readers just beginning to think about the sociopolitical realities of stripping, the ethnography introduces the contemporary debates in a straightforward, thorough, and comprehensive style.

Would you recommend this book to someone who is familiar with academic research and theory on stripping and sex work?

Sounds absolutely accurate and fabulous. I will be reading it. Why is there a picture of Mary’s on the front cover though?

Great review!