We <3 $pread

In honor of International Sex Workers’ Rights Day, the Feminist Press is releasing a retrospective anthology of $pread Magazine today. Current and former Tits and Sass co-editors got together to write about our nostalgic love for the magazine and the way it’s inspired our work.

Bettie, Tits and Sass founding editor emeritus: $pread magazine was walking (gracefully) toward its end when I was a bouncing baby ho, but, gee, what an amazing lil era. For a generation of workers who were lucky enough to see it begin I imagine it felt like what starting Tits and Sass felt like: Exhilarating, frustrating (deadlines are for nerds), and always eye-opening.

Sex worker-created media is a fascinating thing. It’s a lot like us, right? Sometimes hard to pin down, intelligent, always changing, and steady spilling tea you didn’t even know you were thirsty for. This book is as important as the magazine itself and I wish you could still get back issues! $pread existed to remind us that we have to keep telling our stories. No one else can do it for us. Even if they are constantly trying.

Also, $pread taught me that I should pay my taxes, so thanks for keeping the IRS off my ass.

Catherine, Tits and Sass founding editor emeritus, former $pread editor: I remember the first time I heard about $pread, in an article in Bitch, during an era when feminist publications didn’t cover sex work politics with nearly the frequency they do today—or, at least, didn’t include sex workers’ own voices, rather than speaking for us. I had already begun stripping in San Francisco, but was somewhat unfamiliar with the term “sex worker” or the burgeoning media movement. The Bitch article had me fascinated, and I soon found my own copy of $pread in my local indie bookstore.

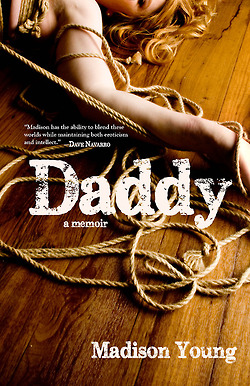

Madison Young’s memoir Daddy tackles head-on the daddy issues sex workers are always accused of having. Young skillfully and responsibly presents her journey from a little girl who misses her daddy to an accomplished gallery owner, feminist erotic film producer, author, and “sex positive Tasmanian devil.” She begins by tackling the issue of consent: yours. “I cannot hear the consenting ‘yes’ seep from your lips,” she writes, “but by the simple turn of this page you will be physically consenting to this journey, this scene, between you and I.”

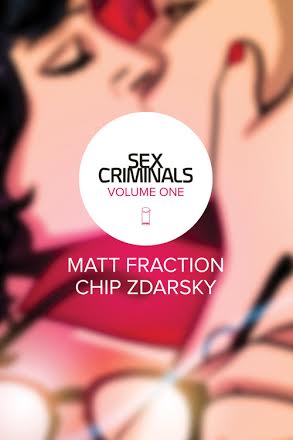

Madison Young’s memoir Daddy tackles head-on the daddy issues sex workers are always accused of having. Young skillfully and responsibly presents her journey from a little girl who misses her daddy to an accomplished gallery owner, feminist erotic film producer, author, and “sex positive Tasmanian devil.” She begins by tackling the issue of consent: yours. “I cannot hear the consenting ‘yes’ seep from your lips,” she writes, “but by the simple turn of this page you will be physically consenting to this journey, this scene, between you and I.” Two people who stop time when they orgasm team up to rob banks is Sex Criminals’ basic premise. Written by Matt Fraction with art by Chip Zdarsky, it’s a fairly new comic that’s been getting a lot of attention. The book sounds like it will be a fun sci-fi romp. And it really is. There’s chase scenes and puns and a musical sequence, but there’s more to it than that. It’s about sex and all its weirdness. How awkward it is. How if you have really, really compatible sex with someone after years of feeling isolated by your time-stopping superpowers, it can be hard not to feel like maybe you should spend all your time with that person.

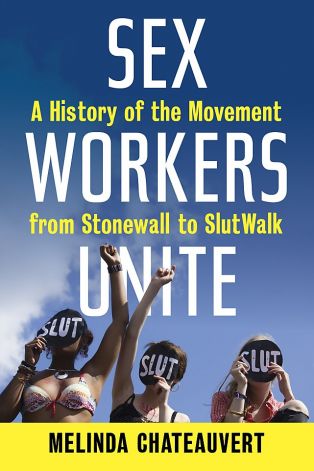

Two people who stop time when they orgasm team up to rob banks is Sex Criminals’ basic premise. Written by Matt Fraction with art by Chip Zdarsky, it’s a fairly new comic that’s been getting a lot of attention. The book sounds like it will be a fun sci-fi romp. And it really is. There’s chase scenes and puns and a musical sequence, but there’s more to it than that. It’s about sex and all its weirdness. How awkward it is. How if you have really, really compatible sex with someone after years of feeling isolated by your time-stopping superpowers, it can be hard not to feel like maybe you should spend all your time with that person. Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s

Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s