by Red Schulte and Cathryn Berarovich of the Support Ho(s)e Collective Alisha Walker was just 20 years old when she had to defend herself against a client who was drunk and violent. She was 22 when she was convicted of second degree murder and 15 years in prison for defending both her own life and the… Continue reading The Right To Survive: The Case of Alisha Walker

Category: Activism

Starting To Show Up: An Interview With SWOP National’s President, Savannah Sly

SWOP (Sex Worker Outreach Project) is the most recognized name in sex workers’ rights advocacy in the U.S. Currently, they have over 25 chapters around the country, and a board of directors—SWOP National. The only requirements to be a chapter are that March 3rd (International Sex Worker Rights Day) and December 17th (International Day To… Continue reading Starting To Show Up: An Interview With SWOP National’s President, Savannah Sly

Activist Spotlight: Bonnie On Violence And Endurance

Content warning: This interview contains graphic descriptions of police violence and rape, imprisonment, and domestic abuse. Bonnie is a veteran sex workers’ rights activist who has done outreach work in the D.C. area since 2001. She was a HIPS (Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive) client who lived on the streets in Maryland. Later, she was inspired… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Bonnie On Violence And Endurance

Activist Spotlight: Morgan M Page on Trans History And Truth

Morgan M. Page, veteran Canadian trans and sex workers’ rights activist, artist, and writer, recently launched a new podcast focusing on Western trans history called One From The Vaults. Tits and Sass interviewed with her to coincide with the posting of the fourth episode of the podcast. Two of the three episodes you have up… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Morgan M Page on Trans History And Truth

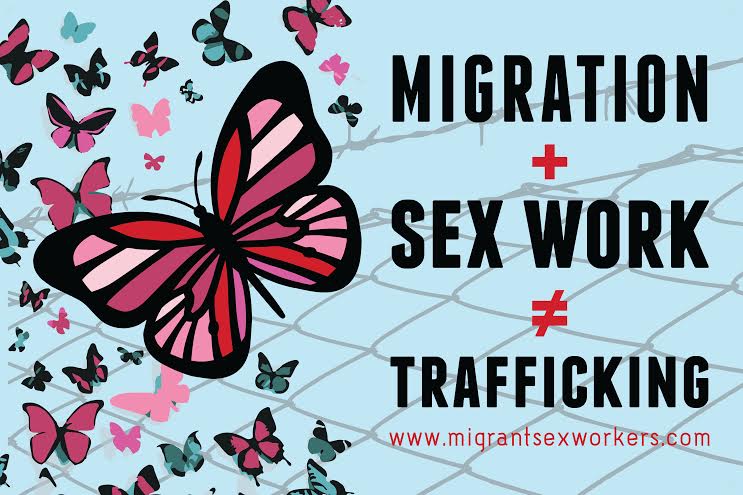

Activist Spotlight: The Migrant Sex Workers Project On Borders and Building Movements, Part Two

I interviewed Toronto’s Migrant Sex Workers Project co-founders Elene Lam and Chanelle Gallant as well as Migrant Sex Workers Project member Kate Zen over video chat. The first part of that conversation, edited and condensed for posting, is here. The group’s vital representation of a population often absent from sex worker activism inspired me. I… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: The Migrant Sex Workers Project On Borders and Building Movements, Part Two