UPDATED FROM 2016: Four years later, Tits and Sass and the sex worker community reiterate our alliance with the Black Lives Matter movement and all communities of color protesting the police nationally. We have updated the list of fundraisers below through which you can demonstrate support. Twitter user @Chateau_Cat has compiled an ever-growing list of… Continue reading Tits and Sass Stands With Black Lives Matter

Category: Activism

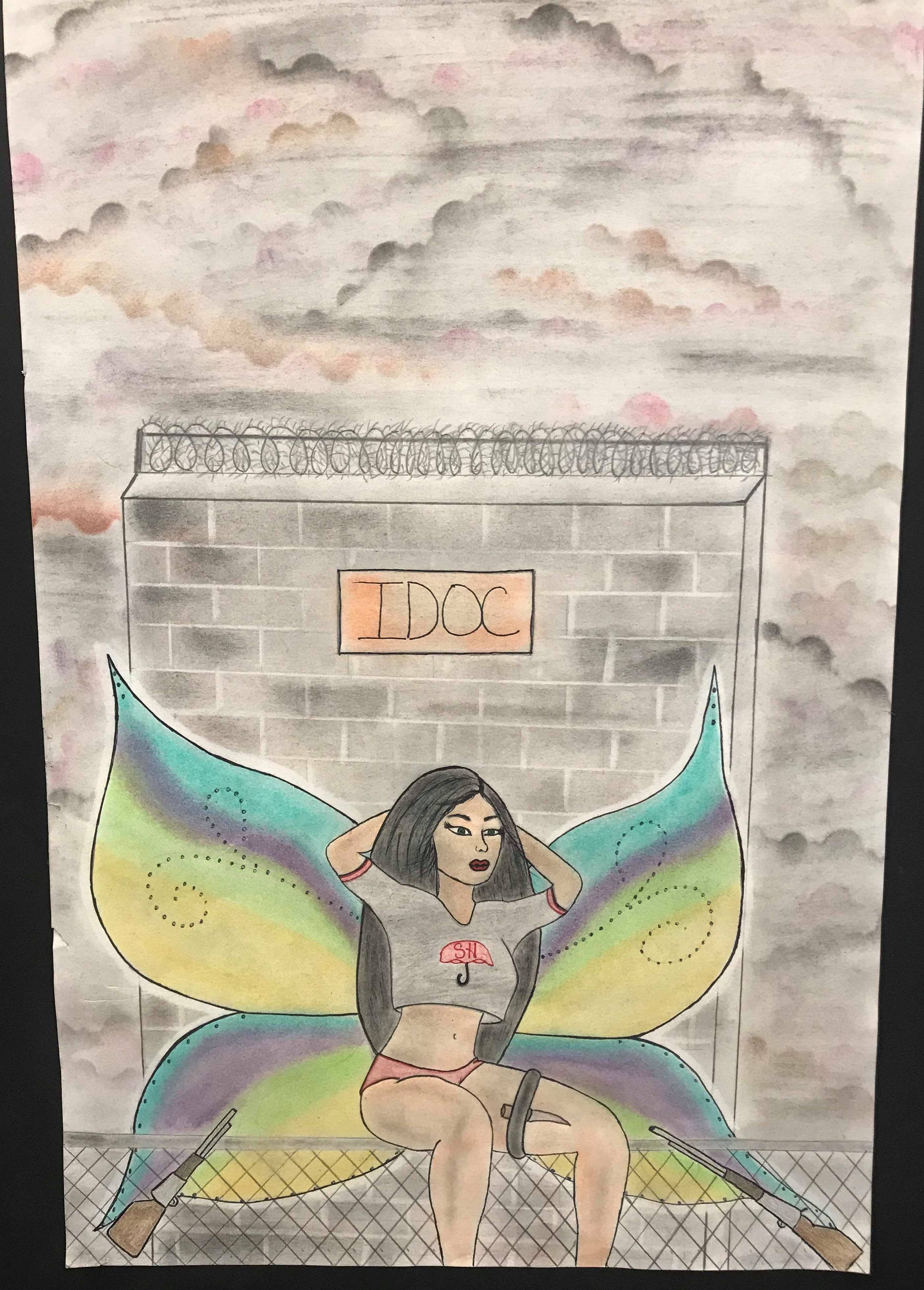

“If U Only Knew How They Were Really Doing Us”: Inside/Outside Communication During A Pandemic

by Alisha Walker and Red Schulte (written by Red, with editing and considerable input from Alisha) Alisha Walker is a 27-year-old former sex working person originally from Akron, Ohio. She was criminalized for an act of self-defense when a regular client threatened her life and the life of a fellow worker in January 2014. A… Continue reading “If U Only Knew How They Were Really Doing Us”: Inside/Outside Communication During A Pandemic

International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers: Reliving the Decade You Survived

By Caty Simon and Josephine Ten years ago, the remains of four sex workers — Melissa Barthelemy, Megan Waterman, Maureen Brainard-Barnes and Amber Lynn Overstreet Costello — were found close to Gilgo Beach, near Long Island, New York. The bodies were unearthed after a frantic 911 call from another worker: Shannan Gilbert spent 21 minutes… Continue reading International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers: Reliving the Decade You Survived

The Massage Parlor Means Survival Here: Red Canary Song On Robert Kraft

As we gathered on the busy street corner in front of the Queens Public Library in Flushing on Friday March 29th, over one hundred community members heard our cry: “性工作是真工作!” Sex work is work! The police had blockaded Red Canary Song members from the library steps, protecting the carceral narratives that were being pushed inside… Continue reading The Massage Parlor Means Survival Here: Red Canary Song On Robert Kraft

The Racism of Decriminalization

Since I began writing this piece, both Scarlet Alliance and SWOP NSW have issued an apology to migrant sex workers for their part in the SEXHUM research. This is an unprecedented move in the right direction for peer organizations. I hope that there will be more attempts in the future to empower migrants and POC,… Continue reading The Racism of Decriminalization