Maria Riot, a member of Argentine sex worker trade union AMMAR, contacted Tits and Sass after the Women’s Strike this month, eager to talk about how her organization participated in the event in their country. AMMAR has maintained a strong presence in Argentina for more than two decades, and its many bold campaigns have often… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: AMMAR Rep Maria Riot On Putas Feministas and Participating In The Women’s Strike

Category: Activism

White Feminism, White Supremacy, White Sex Workers

A provocative critique of anti-trafficking celebrity spokesman Ashton Kutcher and the rescue industry complex penned by sex trafficking survivor (and Tits and Sass contributor) Laura LeMoon is making the rounds. Predictably, white people are pissed. “Kutcher is just trying to help!” exclaim my white, cishet acquaintances on Facebook, clearly missing LeMoon’s point that “being a… Continue reading White Feminism, White Supremacy, White Sex Workers

Sex Workers And Scabs: Mixed Feelings After The Women’s Strike

I was a scab on Wednesday during the Women’s Strike. Too broke and disorganized as usual, still messily addicted, I ended up having to see a client. And sure, I wore red, and I limited my shopping to the South Asian woman-owned convenience store down the street, and I tried to allow the organizers’ reassurance… Continue reading Sex Workers And Scabs: Mixed Feelings After The Women’s Strike

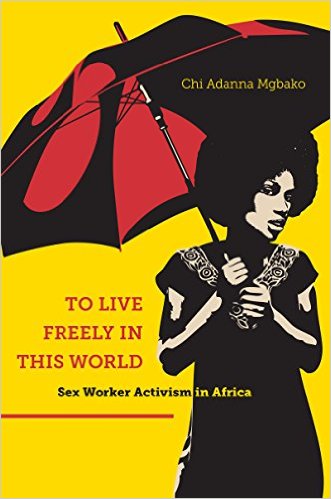

To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism In Africa (2016)

A version of this review originally appeared in issue 19 of make/shift magazine In March 2016, South African deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa made a historic announcement of a nationwide scheme to prevent and treat HIV among sex workers, proclaiming, “we cannot deny the humanity and inalienable rights of people who engage in sex work.” Though… Continue reading To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism In Africa (2016)

Rest In Power, Sharmus Outlaw

Sharmus Outlaw, longtime trans, HIV, and sex workers’ rights activist, died in hospice care at the age of 50 on July 7th from lymphoma. Her death was hastened by systematic healthcare bias: she endured a long delay in processing her Medicaid application because doctors were “confused” by her gender marker, and faced numerous other difficulties… Continue reading Rest In Power, Sharmus Outlaw