Activist Spotlight: BARE on the Mass Closure of Strip Clubs in New Orleans

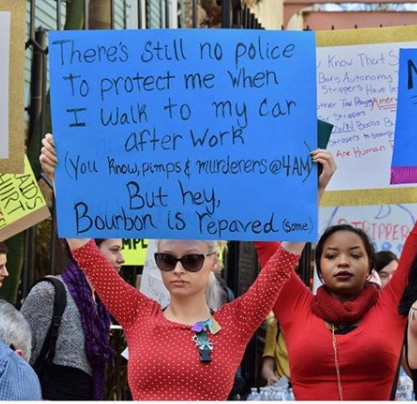

An unholy mix of gentrification and trafficking hysteria created the perfect political climate to allow law enforcement to shutter several New Orleans strip clubs, leaving scores of dancers unemployed. The Bourbon Alliance of Responsible Entertainers rapidly sprung into action; they disrupted the mayor’s press conference and organized the Unemployment March the following night, which drew national attention. I talked to them about the situation in NOLA, their strategy, and their future plans.

So, to start, what is BARE? How long has BARE existed and what kind of activism does BARE do?

Lindsey: BARE is the Bourbon Alliance of Responsible Entertainers. We are an organization run by strippers, for strippers. I started coming to meetings a few months ago, but some of our members have been at this since the Trick or Treat raids of 2015. What we do first and foremost is provide a voice that’s been previously underexposed during the city’s assault on strip clubs: the voice of actual strippers. We’re attempting to work with city officials to influence policies and decisions that affect us. Outside of that, we really just want to foster community among dancers and show the people who don’t understand us that we are valuable members of the New Orleans community. During our first ever charity tip drive, participating dancers donated all of their tips from a Friday night’s work to a women’s shelter. Strippers literally paid that shelter’s rent for six months!

Lyn Archer: I arrived in New Orleans after being laid off from two seasonal jobs in a row, one in secretarial work and one in hospitality. I was on unemployment and got a job cocktail-waitressing at a Larry Flynt drag club. One night, a few weeks before Christmas, the club closed without notice and let everyone go. That’s when I saw how quickly fortunes could reverse on Bourbon Street and how little protection there is for workers. My first week on Bourbon, I was the likely the only stripper that didn’t realize that Operation Trick or Treat had just happened. I entered a work environment where strippers were scared, mgmt was over-vigilant, and customers were scarce. Everyone seemed confused about “the rules.” I later learned that’s because what’s written into the city code about “lewd and lascivious conduct” is different than state law and different than federal law. But these supposed “anti-trafficking” efforts are a collaboration of badges. Undercover agents from many offices move through the clubs. I began researching and writing on this for my column in Antigravity, called “Light Work.” I began to see how a feedback loop between press, law enforcement, self-styled “anti-trafficking” groups and civic policymakers can cause so much destruction for people they haven’t even considered. The club I started at was the first to close. The club was inside a building that was the house Confederate president Jefferson Davis lived in. The house I live in was the home of a Confederate general. We are working against, while inside-of, unfolding histories that are deeply, deeply violent. The more I learn about the history of sex worker resistance in New Orleans, the more I know this fight is lifetimes old and will replicate itself if we do not end it entirely.

For our readers who’d like to help, we put together a list of local organizations which stand against white supremacy and fundraisers for victims of the white nationalist violence at Charlottesville:

For our readers who’d like to help, we put together a list of local organizations which stand against white supremacy and fundraisers for victims of the white nationalist violence at Charlottesville: