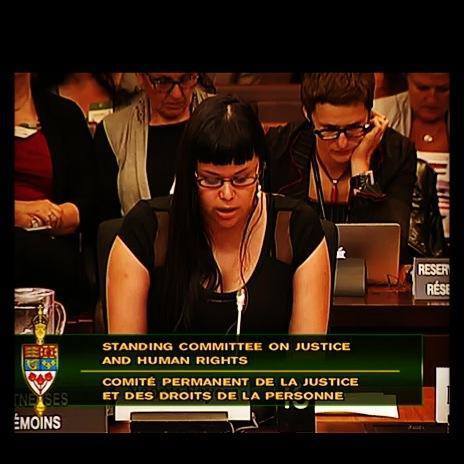

When I woke up in Ottawa back in July 2014 after flying in from out west, there was a huge knot in my stomach. I did not want to go to the morning hearings on C-36, the anti-prostitution bill proposed in response to the Bedford decision that had invalidated three sections of Canada’s prostitution laws. But… Continue reading Testifying In Vain

The Week In Links—March 27th

Brooke Magnanti’s “deranged Samuel Pepys” of an ex-boyfriend actually kept his own diary where he talked about her sex work: so much for his claims that she made it all up, inspired by dead sex workers she saw in the morgue. Elizabeth Nolan Brown explains why the lay-feminist should also be glad that the Senate… Continue reading The Week In Links—March 27th

Activist Spotlight: Meg Vallee Munoz on Compassion, Coercion, and Complexity

Meg Munoz became an escort at age 18, and had a relatively good experience working. She then took a break from the business for two years. Some time after her return to the work in order to pay for college, a close friend turned on her, blackmailing her and forcing her to turn over all… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Meg Vallee Munoz on Compassion, Coercion, and Complexity

You Cannot Consent To Being Treated Illegally: An Interview With Corinna Spencer-Scheurich

I’m currently in the beginning stages of suing local Portland strip club Casa Diablo. So of course when last fall the Oregon chapter of the National Association of Social Workers hired lobbyists from lobbying firm Pac/West to find out what protections strippers need and to craft a bill that offers these protections, I was very… Continue reading You Cannot Consent To Being Treated Illegally: An Interview With Corinna Spencer-Scheurich

The Week In Links—March 20th

HIPS is seeking donations for their new stationary space! HIPS’ mobile outreach program, now over 20 years old, is expanding into a brick-and-mortar location which will offer medical, mental health, and drug treatment services as well as their usual harm reduction, advocacy, and community services. A new take on a tired trend: in this… Continue reading The Week In Links—March 20th