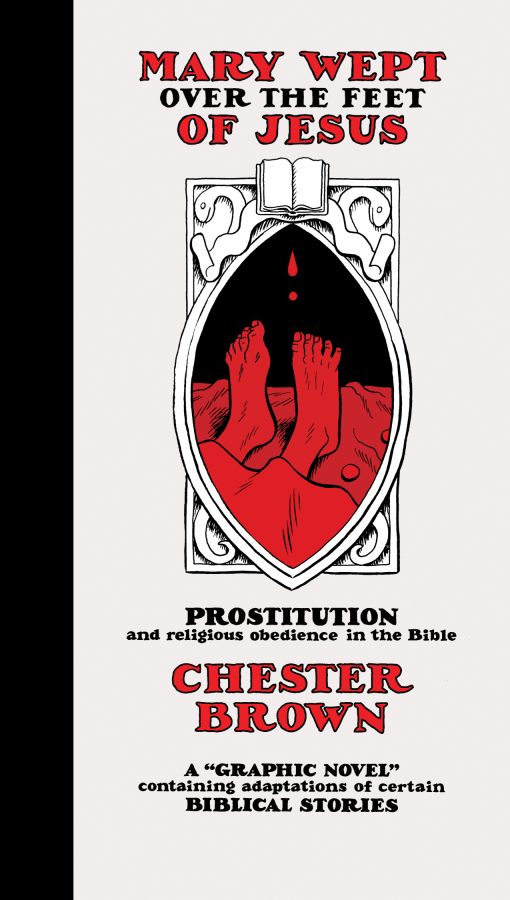

Canadian comic artist Chester Brown is probably the most well-known punter-writer our there. His latest, Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus: Prostitution And Religious Obedience In The Bible, is an analysis of the Bible as a graphic novel. (Maybe Brown likes illustration because most clients need pictures in their books.) This review of his newly published book is composed of an edited version of an email and g-chat conversation between Tina Horn and Caty Simon.

Canadian comic artist Chester Brown is probably the most well-known punter-writer our there. His latest, Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus: Prostitution And Religious Obedience In The Bible, is an analysis of the Bible as a graphic novel. (Maybe Brown likes illustration because most clients need pictures in their books.) This review of his newly published book is composed of an edited version of an email and g-chat conversation between Tina Horn and Caty Simon.

Caty: I was surprised by Chester Brown’s Christianity as demonstrated by this book. In its afterword, Brown explicitly identifies himself as a Christian, albeit one focused on mysticism who’s “interested in personally connecting with God, not in imposing my views on anyone else.” His avowed, classic libertarianism in his sex work client graphic novel memoir Paying For It (2011) would’ve had me assume that he was a fervent atheist a la Richard Dawkins. His libertarianism does come up at an interesting point in this book when he puts the words “it’s none of your business how other people spend their money” into Jesus’ mouth when he chides Judas for judging Mary because she spent money on anointing oils for Jesus’ feet rather than on charity.

Tina: Especially when you consider that he ran for Canadian Parliament in the Libertarian Party! This was in the years right before Paying for It came out.

Caty: So he’s actually having Jesus Christ parrot his party politics—that’s ballsy.

Tina: When I was a teenager, I thought Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis was the shit, because it taught me more about what the Bible actually teaches than most of the aggressive Christian kids at my high school. Mary Wept puts me in mind of C.S. Lewis: a Christian highlighting the hypocrisy of other Christians through rational interpretation of their text.

Caty: When people say that Judeo-Christian values oppose prostitution, it gets me fuming, because it’s a lot more complicated than that. There are plenty of heroic whores in the Bible, and many more Biblical heroines who explicitly had transactional sex at some point in their stories. So I enjoyed how Brown highlights the stories of women like Rahab, the prostitute who sheltered Hebrew spies from discovery when they scouted out the city of Jericho, and Tamar, the woman who whored herself out to her father-in-law in disguise in a complicated plot to expose his hypocrisy. I only wish he’d included the story of badass Judith, the woman who beheaded the general Holofernes as he lay drunkenly asleep in her tent after possibly purchasing her services, ushering the Hebrew army to victory.

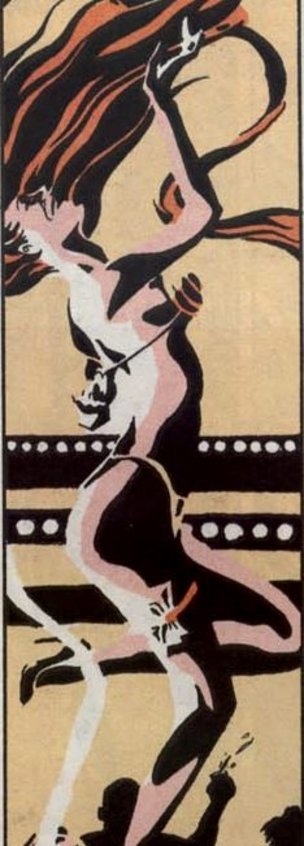

Maybe Brown felt like he just couldn’t compete with all the exquisite Renaissance and Baroque era artistic renditions of Judith in her moment of triumph, like this one:

But I think the real reason Brown didn’t include tales like Judith’s is because he seems more focused on outlining these sex work-related Biblical narratives in order to glorify sex workers’ clients. He has a convoluted thesis going about men whoremongering as a transcendent challenge to rigid religious dogma. This ascribes nonexistent significance to an activity which is really morally neutral, and it obscures all these awesome sex working Biblical women in stories which are about them. In a memoir about being a sex work client like Paying for It, centering the client perspective makes sense. But in a book like this, it feels beside the point. I’d love to see how this material would look tackled by a sex worker amateur Biblical scholar/comic book artist.

Tina: The book does explore the subjectivity of the clients more than that of the women. Brown’s reinterpretation of a lot of these stories seems to amount to, “God totally says it’s ok to be a whoremonger!” Which is great, but I would love to see more, “God says it’s totally cool to be a whore!” Not because I personally need the validation, but because undermining Christian values with their own text is a longtime favorite sport of mine.

Caty: So, what do you make of Brown depicting God as some sort of Biblical version of a WWE wrestler? His God is BUILT.

Tina: He is built similarly to some of the other characters, which sort of makes literal the whole “in his image” thing.

Caty: Brown embodies God—that’s weird for me as a Jew.

Tina: God has a cute bubble butt. What’s God’s glute routine? Cloud Stairmaster?

Caty: If that’s Brown’s go-to image when thinking of the Divine, it kind of makes sense of all the neurotic dweeby guy insecure inner monologs he had going during sessions in Paying for It.

Tina: It seems to me that the character who is the stand-in for Brown is Matthew, right?

Caty: In Matthew’s story the impoverished sex worker is, again, only instrumental—she’s literally his muse, inspiring him!

Tina: So we have a bit of the magical hooker thing happening, right? The disenfranchised person whose very existence is some profound insight, a catalyst for the protagonist’s growth and understanding.

Caty: I thought it was interesting when Brown related in his VU Weekly interview that he actually did encounter a woman begging who propositioned him for transactional sex, just as Matthew did. But Brown actually took her up on her offer. He says he couldn’t have Matthew doing that because, in his narrative, he needed him to go back in and write.

Tina: He is depicting Matthew as someone who knowingly constructed the narrative, who placed a subtext about whore lineage in his writing for others to find.

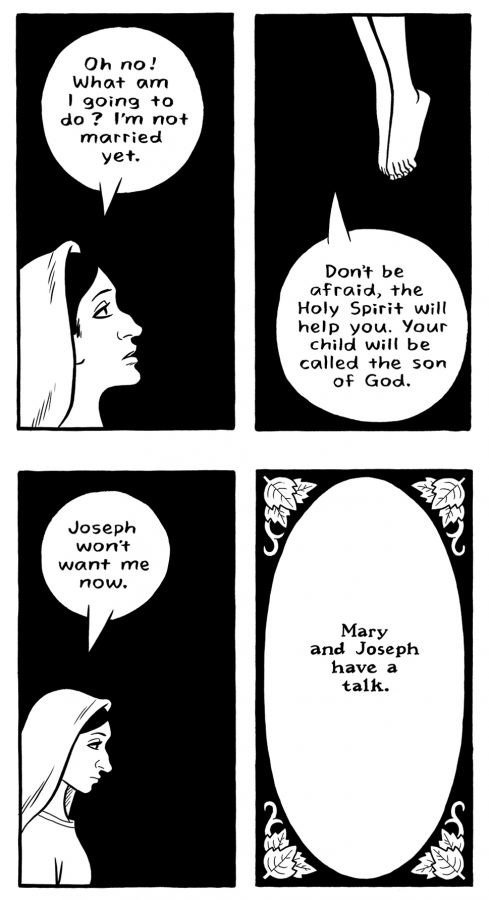

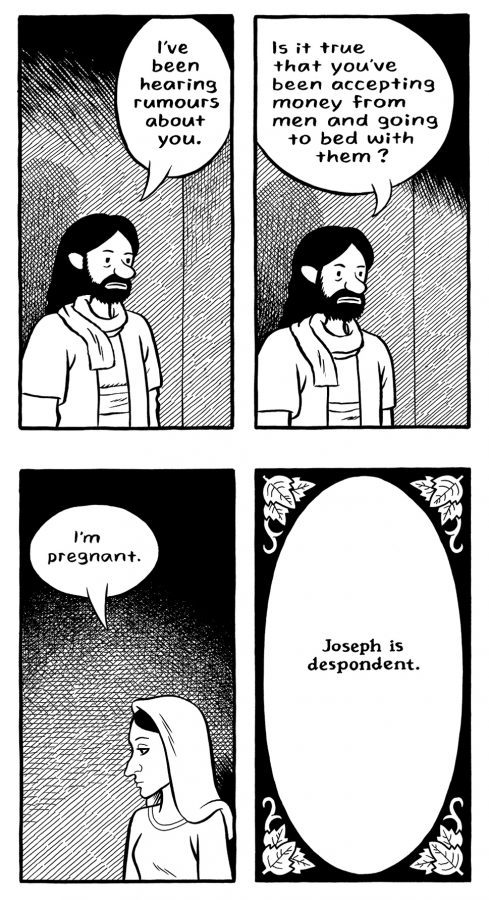

Caty: I do like the idea of Jesus’ mother being a sex worker as hinted at by a gospel genealogy containing famous Biblical sex workers and/or women who informally traded sexual labor.

Tina: One thing that I think is very characteristic of Brown, as well as Joe Matt and Seth, who are his comic community, as well as even R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, and the rest of the SF ZAP comic folks, is the way they have characters who literally speak the author’s philosophies. And whether you enjoy that really depends on whether you like reading cartoons in which a character walks around with a thought bubble around what basically amounts to a personal essay.

So, for example, Matthew is a stand-in for Brown here, and he delivers the book’s thesis, which is, “These are women who took sexual initiative for social advantage.” He even explains Brown’s own reasoning for including Bathsheba and Ruth, who are really more seductresses than whores.

Brown’s Drawn and Quarterly crew also definitely takes some of the same heat as the San Francisco Zap Comix folks of the 60’s (Crumb, S. Clay Wilson)—that heat being that they’re so wrapped up in their own heads they end up portraying women like objects.

And coincidentally, Crumb also made a comic book Biblical adaptation, of Genesis.

Caty: Doesn’t Brown cite that in his notes as one of his influences for Mary Wept, along with illustrated Bibles he had as a child?

Tina: I think Brown took more liberties than Crumb. Part of the delight of Crumb’s Genesis is you see the white bearded God portrayed by the same artist who drew himself riding piggyback on big-thighed ladies in knee socks.

Caty: Brown revolutionized my understanding of the book of Ruth. Maybe I was too young when I studied it the first time, but I never thought about Ruth seducing her boss, Boaz, as survival sex work—which of course it was. Naomi is the one who asks her to do it, and yet the text doesn’t understand it as Naomi pimping Ruth out, but valorizes Ruth for it, because it’s just one of a long list of things Ruth does to prove her loyalty and love for her mother-in-law. Rereading Ruth, I find that Brown even downplayed the transactional sex elements within the story—Boaz BUYS Ruth as his wife when he buys the plot of land that belonged to Elimelech, Naomi’s late husband, and Ruth’s father-in-law.

In the comic, Boaz makes sure to mention that he’s protecting Ruth from sexual assault. I admit, I thought that was Brown’s embellishment, but looking back at the original text, Boaz actually mentions this not once, but twice. No one even brings up the possibility of sexual assault until he repeats, several times, ‘OH, LOOK AT WHAT A SAINT I AM, BEING THE ONE THING STANDING BETWEEN YOU AND RAPE.’ Guess he was an original Biblical white knight type.

Tina: So Ruth is the original Pretty Woman. And Boaz is the Biblical OG white knight.

The thing I liked about the way Brown depicted both Ruth and Tamar’s story is that there were all these spiritual and civil laws about morality and propriety, and these women were disenfranchised by these laws. So they figured out how to subvert them using sex. Nowadays, we might have fewer rules about your father-in-law deciding whom you can marry, but there are still complex infrastructures in place that keep women from being able to obtain security and power. And sex workers today are still using sex to undermine those rules.

Am I giving him too much credit? It excites me in contrast to how oppressive and anti-feminist Christianity has always been in my life.

Caty: As a Christian book, it’s certainly a breath of fresh air. And although looking at the sheer volume of the notes included at the back of the book made me laugh initially, I am glad he did his due diligence backing up his Biblical assertions with scholarship, because if it was otherwise that’d make the book even easier for the Christian mainstream to dismiss as crankery.

I had to admire Brown’s understanding of prostitution in the Bible as evidenced by those notes—for example, he notes the other negative connotation sex work had in that era, of idolatry/temple prostitution in contrast to the Hebrews’ rigid monotheism.

Contemporaneously with the Bible, the other cultures surrounding the Israelites practiced temple prostitution. Which is the source of a lot of the vitriol directed against prostitution Biblically. It wasn’t the condemnation of prostitution so much as of paganism.

Tina: It’s also about the relationship of religion to power, and the way monotheism and patriarchy are linked.

Caty: The Bible is the product of a huge infowar by monotheism and patriarchy against polytheism and matriarchy. Which was a violent conflict—the Bible chronicles the conquest by the Israelites of these surrounding pagan and sometimes matriarchal cultures, a manifest destiny supposedly commanded by God.

Tina: This also makes me think about the way some people see sex workers who want to do the work as brainwashed by the patriarchy. So, it’s important to revisit the history of prostitution in order to see its origins as a site of matriarchy and spiritual power for women.

Caty: Well, we don’t want to romanticize that history, either. We know very little about it. I’m sure a lot of accusations connecting the surrounding pagan cultures to misdeeds like human sacrifice were part of the ancient Israelite PR campaign against them, the rationale justifying their genocide, but some of it could’ve been true. It’s not like we can go back and interview the women involved in temple prostitution!

Tina: Have you read Neil Gaiman’s Sandman? There was one issue about a stripper who was actually an ancient whore goddess whose dance to “Sister Midnight” kills everyone in the club.

Caty: I remember that! Ishtar fallen on hard times and just dancing to get by like all the other girls in the club.

Tina: We should definitely go to strip clubs looking for ancient whore-goddesses to interview for this piece.

This sort of brings us back to the question of whether we’re happy to have Brown saying, “Hey, let women be whores if they want” or if it’s undermined by his characterization of most of his female characters as magical hookers who teach men something about themselves or life.

Caty: This also goes back to what was both endearing and infuriating about Paying For It. On one hand, it’s laudable that Brown didn’t compartmentalize his own patronization of prostitutes like some clients do. He allows his experiences to put him firmly on the side of sex workers’ rights.

On the other hand, Paying For It makes it clear that Brown isn’t great at depicting sex workers as people outside their interactions with him—people with more complicated politics than “two consenting adults behind closed doors”, or “sex work is work”.

In this book, he basically begins his notes by stating, ‘Some sex worker activists don’t like the use of the term “prostitute”, but I, a man, believe you all should reclaim the term, so I’m going to ignore that opinion.’ He’s mansplaining all the way through being an ally.

Tina: Omg, did you hear that sex work is, totally, like, just like any other job?

Something I’ll give Brown credit for is that his anachronisms ensure that the women come across as very clever and figures like Boaz and King David come across as dummies who think they know what’s best for women—but it’s just because the women manipulated them, put ideas in their head, and sealed the deal with sex.

Caty: But even having his sex workers be these shrewd calculators in a world full of buffoonish men doesn’t really let Brown off the hook for his reductionist picture of them. It’s just playing back into that patriarchal trope about women and their wiles. These sex workers still aren’t human beings apart from their work. For example, Ruth is often read as a platonic love story between two women. Lingering more on that would’ve fleshed out these characters’ humanity. But Brown limits his portrayal of these brave, canny, loving Biblical sex working women to their work.

I haven’t read Brown’s graphic novel, but I loved reading this review! Thank you, ladies, for publishing this. It was a great adventure!

I’m a huge fan of Riane Eisler, and she tackles a lot of the biblical history as connected to patriarchy, especially in Sacred Pleasure. Back then, “pagan” was pretty much synonymous with “Goddess worshiper”. Growing up, I remember the word “pagan” having a very creepy, sinister feel to it. Not having followed a terribly religious life, revisiting the concept of paganism as an adult via Eisler was pretty eye-opening. And looking back, it was fascinating that I was made to “fear” anything pagan as a child in church (and hence, never questioned it). Interestingly, I remember also feeling a culturally-induced “fear” of sex and men: being prescribed to behave in certain ways lest men “get the wrong idea”. Thank goddess I challenged that for myself at 21 when I discovered the delights of penises and lots of delicious, indiscriminate sex with strangers.

Sex work was as common for people to do during biblical times as waiting tables is today. Actually, probably more common. I remember a discussion with an academic friend of mine and several fellow sex workers for her PhD dissertation about different vignettes in the bible, and our views on their meaning. I learned during that discussion that the word “foot” was a euphemism for “penis” back in those days- and that shed a whole new light on the story of the anointing woman. Also, the origins of the “symposium” was a gathering of men drinking and carousing, often with sex workers. So when Jesus attended symposia in the bible, you know what he was up to. He liked a good orgy just as much as the next person.

Also, the origins of the “symposium” was a gathering of men drinking and carousing, often with sex workers. So when Jesus attended symposia in the bible, you know what he was up to. He liked a good orgy just as much as the next person.

Putting women “in their place” was a goal of monotheistic cultures, and it’s been achieved methodically and calculatedly over time by the perpetual denigration of sex and pleasure. It continues today, of course, but it’s exciting to be a part of a class of people embodying the challenge to it!!

Caty and Tina, thanks for considering the book in such depth. I will say that Caty’s last point matched the opinion of the sex-worker I see on a regular basis (the woman I call “Denise” in Paying For It). After reading Mary Wept, she said something like, “Those women were more than prostitutes.” She felt I hadn’t communicated that properly. She did have nice things to say about the book, too, of course.

I loved Denise a lot in _Paying For It_ so thank you for telling me that, Chester–I appreciate it!

[…] we talk about Chester Brown’s Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus Tina Horn and Caty Simon at Tits and Sass: ‘But I think the real reason Brown didn’t include tales like Judith’s is because he […]

Omg

I can’t believe he commented and was still subtly condescending. “The sex worker who I see (who is just like one of you!) also thinks the same thing that you guys have written so well! ”

It just brings to mind Archer, when someone says, “I don’t want to be racist but -” and the other person responds, “But you’re going to power through it?”

“I’m an ally but – I’m going to disresgard what workers actually have to say about a slur and tell you, what I, a mere comic book writer, think you should do!”

I enjoyed this review. Honestly I found it more entertaining than “Paying For It”, which just reminded me of my milquetoast hobbyist clients who feel the need to run online and not just comment on whether the session was enjoyable or not, but to describe the woman in detail and write out the stories in their head for other men to enjoy.