Adrienne Graf and Annie O’Niell are two social workers whose focus has been sex workers. O’Niell has experience as a sex worker and Graf is an ally. Together, they have facilitated workshops at the university, state and national level on how to work with students in the sex industry. Here, they have a conversation about their work as social workers reaching out to sex workers.

Annie: How does your work with sex workers intersect with social work?

Adrienne: Even before I started doing social work I have always been in community with many types of sex workers. I was privileged to get to interact with many different people around this topic, and receive a lot of education and exposure that my current work is based off of. So from very early on in my young adulthood I was thinking about sex work as legitimate labor and sex workers as people in my community facing different types of marginalization. When I started in social work, I just always thought of social work as a profession working with and for various communities and sex workers are in our/those communities communities. So for me there was never a moment of “Wait, does social work address the concerns and experiences of people in the sex industry?” I always assumed that of course it would. Cue massive disillusionment.

I first started working with people in the sex industry (in a social work capacity) when I was working at Portland Women’s Crisis Line, in the Sex Industry Outreach Program. I was meeting with people on the homelessness continuum who were engaged in survival sex and outdoor work. Our work was paired up with a mobile medical van from a local harm reduction agency. In my current role for past six years I have been working at a Women’s Center with students in at a state university in a large urban area who are survivors of interpersonal violence. We know, of course, that all sorts of people experience interpersonal violence, and sex workers were seeking out my services, but were hesitant to bring up their involvement in the sex trades.

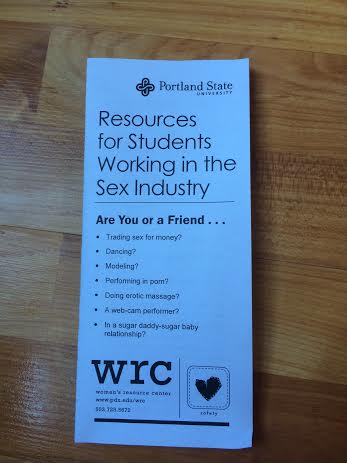

I (hopefully) created an environment where people felt like they could be honest, and referrals kept pouring in. Time and time again I would hear students say: “I can’t tell anyone here; you are the first person I have told; I feel so isolated.” I was unofficially ad-hoc providing resources for student sex workers, so I decided to try and institutionalize my work. I talked with my coworkers at the Women’s Center about it, and drafted a statement of support and put on my centers website.

I met Annie a few years ago and she had mentioned that it was unique that our Women’s Resource Center had such a statement. She was just starting a research study examining the resources (or lack thereof) in Women’s Centers across the US. We’ve been noticing that very few campus organizations and Women’s Resource Centers are offering resources, services, or information about students working in the sex industry and that some of the conversations we have been having don’t have a model or a lot of research focused on student sex workers. So we decided to start training colleagues and other service providers in our community and state on best practices for working with and supporting students in the sex trades.

So, Annie, tell us how your work with sex workers has intersected with social work.

Annie: I started working with sex workers through a harm reduction street outreach program about eight years ago. When I started doing this work, I learned so much from the folks I was working with about how hard it was to get their medical, legal, and social service needs met. Early on, I learned how judgmental social service organizations were and how important it was to share resources, advocate for harm reduction, and educate social service providers who were working with sex workers about how to be more accessible.

There is so much to say here about what I learned from the folks I worked with, the skills that they utilized to resist these various forms of stigma, and oppression, and the privilege that I had as both a service provider and within my own experiences working in the sex industry. I started my Master of Social Work program and was blown away by the level of offensive commentary about people in the sex industry. During this time, I had started to do sex work and came out in one of my classes. I just wanted people to know that anyone could be doing sex work and there were a lot of different realities and ways to engage in the sex industry, and that privilege and power impact sex workers in a variety of ways.

Fast forward, I am in a PhD program studying and researching students working in the sex industry, sex worker activism, and the influence anti-trafficking and “rescue-based” interventions have on how social workers approach their work with people working in the sex trade.

Adrienne: How would you describe the current social work landscape related to sex work/ers?

Annie: Honestly, I sometimes get overwhelmed when I think about this. It feels like certainly, the dominant view is that everyone involved in sex work is a victim. I think that the influence of anti-trafficking campaigns and radical, abolitionist feminists locally and globally is so pervasive and dominates social work education and practice. If I am having a conversation with a new person about my research being around sex work, the immediate response is almost always something like, “Do you know this organization that works with exploited women?” or… “Oh, I know about sex trafficking”…or “Maybe you would like to speak at this human trafficking event that I am hosting?”

I think if we just look at Project Rose and the Arizona State University School of Social Work, and the Monica Jones case, it gives a good look at the current climate around sex work in social work. Even in the case of Jones, a student in the SSW, who has been an advocate for sex worker rights (not rescue), they are still intent on arresting her as a sex worker in order to “help” her get out of the life. This is one of the most horrific, upsetting, and rage-invoking interventions of all time. All over social work and especially in the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics informing social workers of what their professional conduct should look like, we see messages about promoting justice and working towards ending oppression. Project Rose does exactly the opposite of this. Witnessing its targeting of people of color, trans folks, immigrants, youth, and other marginalized communities through ambiguous prostitution laws and undercover stings, we know that oppression has a firm grasp and voice in the field. Stephanie Wahab and Meg Panichelli articulated this in their Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work piece on the problematic use of these types of coercive interventions with sex workers. Programs like Project Rose send the message that you can only be a social worker if you are a) not a sex worker and b) see sex workers as people that need to be rescued.

At the same time there are some critical feminist social work scholars working to change the landscape of social work in relation to sex work. Folks like Stephanie Wahab, Lacey Sloan, and Moshoula Capous-Desyllas immediately come to mind. Then of course there are many radical social workers who are in the field and doing phenomenal work. Some of the awesome organizations that we have been influenced by include: Women With a Vision, Sex Workers Project, Best Practices Policy Project, Project SAFE, Persist, BETSY Project, Young Women’s Empowerment Project, Queers for Economic Justice, and the many SWOPS and SWOC’s around the country. And we know that there are so many other organizations and projects who have radical social workers working with them.

What are your thoughts Adrienne? Can you comment on your experiences?

Adrienne: There is a growing belief right now in the field of social work that there is a rise in sex trafficking, and that it is this growing, nefarious epidemic that needs to be interrupted by social workers, and that victims need to be rescued. Recently, I was talking with my clinical supervisor who works with Masters Level social work students. In the past several years she has seen a rapidly growing number of students saying they want to work with victims who have been trafficked, that that is their reason for entering social work. Which doesn’t surprise me, because social work has a history of paternalistic, missionary style “aid” with marginalized communities. That is the formation and history of my profession! We can look at Jane Addams and the Hull House, “friendly visitors”, the removal of indigenous youth from their communities and their placement into boarding schools, etc. Social work has always been full of well-intentioned middle class workers who come in to marginalized communities and want to “rescue” people. In social work right now and in dominant white feminism, we need to be really critical about how we think and talk about these issues, and how our ethnocentrism impacts how we think people “should” live their lives. I am deeply troubled with the way that we are discussing other peoples’ lives over and over again in these conversations.

Annie: I just read this article by Amy Rossiter (“Innocence Lost or Suspicion Found: Do we educate for or against social work?”) which really encourages social workers to consider the privilege involved in “helping”; to be critically reflective about our impulses to help and our own social locations; and to consider the ways that it is problematic to assume that we have some kind of “expert” knowledge.

Adrienne: A really dangerous liaison is happening between evangelical trafficking organization and “radical feminists” and social work organizations. There is a history of this, it’s not new. It’s my opinion that in social work there isn’t a critical eye being turned to this work because we are so deeply uncomfortable with sex work and social workers are so deeply invested in their identities as “helpers” and “saviors.” Annie and I present to lots of different audiences and recently I heard some feedback that there was the impression we were “encouraging” students to enter the sex industry, simply because we did not “condemn” the existence of the trades. Moving away from theoretical conversations about “empowerment” and victim/agent dichotomies makes people deeply uncomfortable because you aren’t making an assessment about if you think the sex trades are “right” or “wrong”.

Adrienne: Will you talk more about presenting on students in the sex industry?

Annie: About a year and a half ago I put out a research survey to Women’s Centers at universities about how they are working with sex workers. A lot of the responses were that they weren’t working with them; that they thought sex workers wouldn’t access their centers; or that they didn’t have the funding or staffing for that type of work. Some people stated that there weren’t any sex workers on their university campuses due to their geographical location.

I don’t want to condemn these centers for not doing this work, because I really appreciate their honesty in answering the survey. So many folks were like, “I just don’t know what to do! And…please tell me, I want to be accessible to our students.” Which is so great, and was one of the goals of the survey—that perhaps as people were taking the survey they would think about how they could start being more accessible towards students working in the sex industry (and not just women-identified students). This lack of knowledge and awareness does point to how inaccessible women’s and feminist resource centers can be for many folks. Not just sex workers—also, consider the intersections of identities that sex workers embody. If the feminist centers on campus are inaccessible, the rest of the university is likely to be as well.

I discovered from the results of the survey that there were a few centers that said they worked with sex workers. They had staff who were knowledgeable about the sex industry and could realistically safety plan with students, they promoted programs related to sex worker rights, and they had pamphlets about health and safety for sex workers. It was after we began analyzing some of the findings from this project that Adrienne and I started talking about putting out a safety pamphlet for student sex workers, which led to us to wanting to do further scholarship and collaboration/exploration around the experience of student sex workers.

Adrienne suggested that we apply to present at a Student Affairs Conference so we could connect to and educate some of the people working in higher education. We were accepted to present at the conference, and that started some momentum around getting offers to present to other audiences, including our University’s nursing and clinical counseling staffs, as well as our state’s Attorney General’s sexual assault task force. During our presentation to the task force campus committee, people recognized that they might have personal biases or feelings about students working in the sex industry, but they also started to understand that student sex workers were on their campus and needed to just be supported with where they were at. So far, we have been lucky to have mostly receptive audiences and be a part of some really amazing, first time conversations around this topic.

Adrienne, what has your experience being like with presenting around this topic with me?

Adrienne: I think people have been more receptive to us because they read us as not sex workers, but as professionals, and we are white college educated women. So there is an inherent privilege in that, and that is something that we are trying to be very mindful and critical about when we think about whose voices get included in this conversation and whose are left out.

As both a social worker and a sex worker, I deeply appreciated this article. I try to keep both identities hidden from the other: I don’t want to be fired as a social worker for doing sex work, and I worry that sex work coworkers and clients will somehow not approve of the social work. Perhaps somewhat ironically, I tell them I’m a teacher

I love this. I’m going into an MSW program and am also a sex worker. alison’s comment above sums up a lot of my own hesitation and internal conflict around my two lines of interest and work.

Awesome article; thanks for the work you’re doing, Adrienne and Annie!

I’m finishing up my MSW, and thank you thank you thank you for this article. The ONLY things we have learned about sex work are all about trafficking, pimps, and how to exit “girls” from the system ASAP (including ugly, ugly debates-that-aren’t-really-debates about “well, should we involve police? I mean, I don’t like it but how else will you get the girls out of the system”). Even saying “sex work” instead of “prostitution” or “trafficking” gets ugly looks and long hostile silences from professors and students. I didn’t expect social work to be on top of their game here, but I really did not expect it to be *this* bad. There is just no room for any conversation that isn’t about sex trafficking (and any other kind of trafficking will never get addressed).

This is the first article I’ve ever seen on being both a student and a sex worker. I really appreciate it.