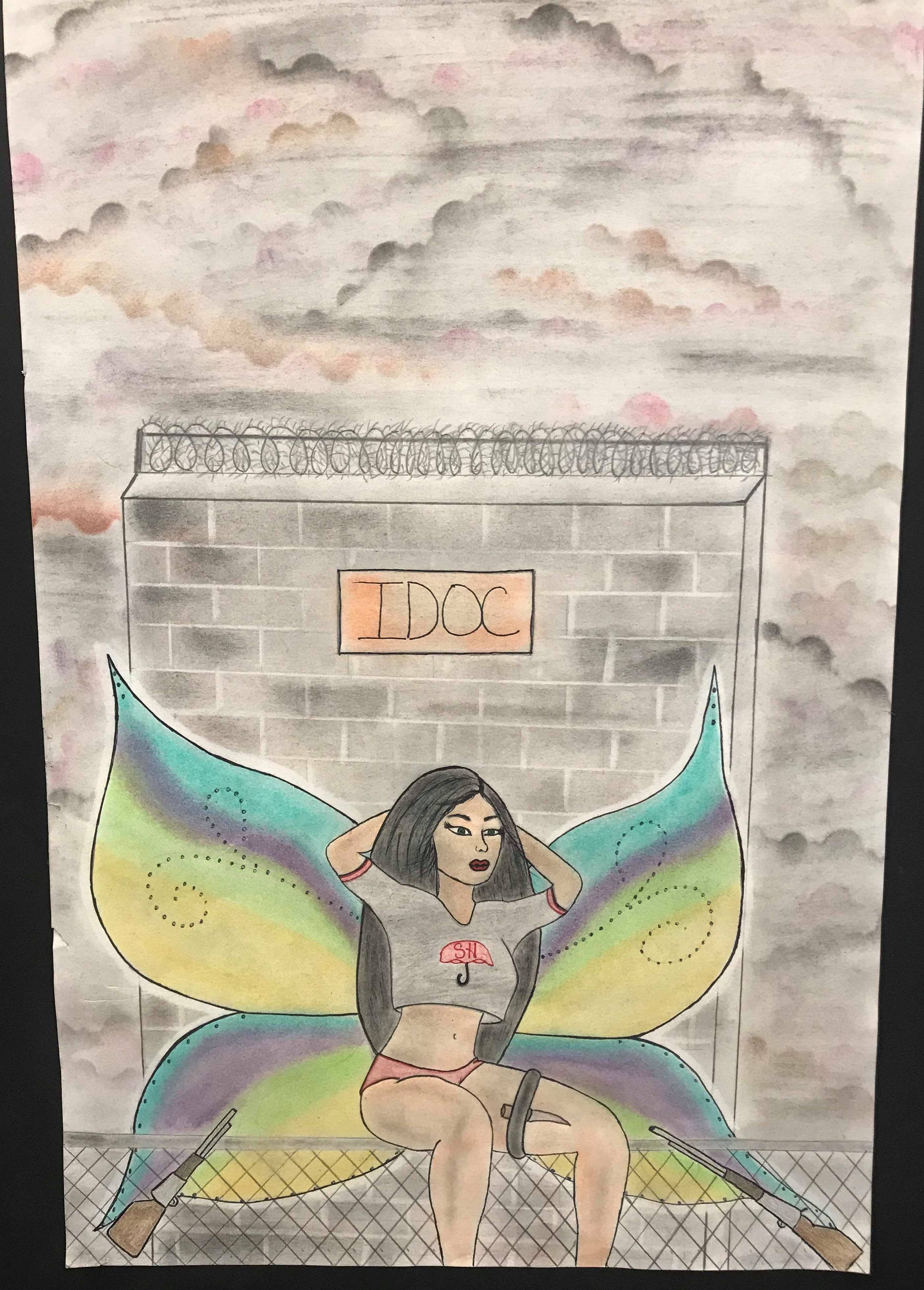

by Alisha Walker and Red Schulte (written by Red, with editing and considerable input from Alisha) Alisha Walker is a 27-year-old former sex working person originally from Akron, Ohio. She was criminalized for an act of self-defense when a regular client threatened her life and the life of a fellow worker in January 2014. A… Continue reading “If U Only Knew How They Were Really Doing Us”: Inside/Outside Communication During A Pandemic

Category: Prostitution

Coronavirus and the Predictable Unpredictability of Survival Sex Work

With the coronavirus hitting a market which has still not recovered from SESTA/FOSTA and the Backpage seizure, sex work has taken a double whammy in a two year period, and it is most adversely affecting those of us who have the least power, influence, and resources. Still, for us survival sex workers—people who work just… Continue reading Coronavirus and the Predictable Unpredictability of Survival Sex Work

The Racism of Decriminalization

Since I began writing this piece, both Scarlet Alliance and SWOP NSW have issued an apology to migrant sex workers for their part in the SEXHUM research. This is an unprecedented move in the right direction for peer organizations. I hope that there will be more attempts in the future to empower migrants and POC,… Continue reading The Racism of Decriminalization

Dennis Hof (1946-2018)

Dennis Hof passed away last week at his Love Ranch brothel after a night of celebrating his 72nd birthday and political campaign. The days following have been filled with an outpouring of discourse about his death, much of which is contentious as people reflect on the so-called legacy Hof left behind. Between his business empire… Continue reading Dennis Hof (1946-2018)

Donna Dalton, Jill Filipovic, And The Eternal Lightness of Anti-Sex Worker Feminist Being

On August 24, a police officer on duty with the Columbus, Ohio police department named Andrew Mitchell shot and killed sex worker Donna Dalton, leaving her two children motherless. Like others who habitually inflict state sanctioned violence onto the bodies of marginalized people, Mitchell says he “feared” for his life, despite friends describing Dalton as… Continue reading Donna Dalton, Jill Filipovic, And The Eternal Lightness of Anti-Sex Worker Feminist Being