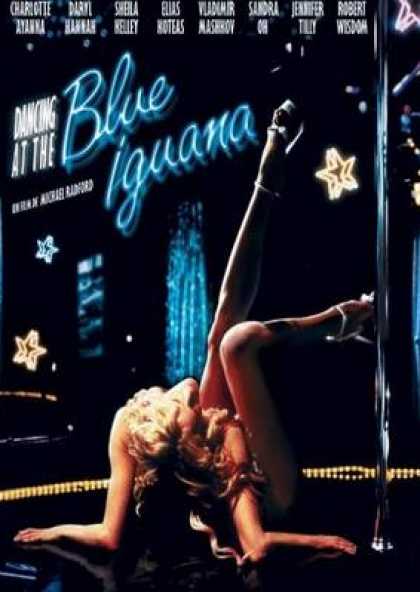

Dancing at the Blue Iguana (2000)

I’ll confess that Dancing at the Blue Iguana is a special film to me. Over ten years ago, I naively watched this film as research before I finally decided to join the ranks as a card carrying exotic dancer.

“Oh God,” I remember thinking after watching it. “Can I really do this?”

Dancing at the Blue Iguana, directed by Michael Radford, is a moody, winding drama that examines the lives of five strippers working at the San Fernando Valley’s Blue Iguana strip club. Jo (Jennifer Tilly), Jesse (Charlotte Ayanna), Jasmine (Sandra Oh), Stormy (Sheila Kelley), and Angel (Daryl Hannah) have dysfunctional, messy lives but ultimately they can depend on each other and are bound by the sisterhood formed in the Blue Iguana’s dressing room.

The film offers a series of snap shots into the girls’ personal lives. And boy howdy, their lives are a collective train wreck. Jo is the hot-headed drug addict that can barely make ends meet. She vehemently denies that she’s pregnant until her workmates force her to fess up. Later, she enthusiastically lactates on her customers. Jesse is the new girl who relishes in her sexual power but finds it damning when she seduces a struggling musician who reveals himself as an abuser. Stormy, the tortured one, rekindles a secret, incestuous relationship with her brother. Jasmine is the club’s requisite icy bitch. She doles out tough love and cynical witticisms to her workmates but surprises us when we learn that she is also a sensitive poet.

Angel made a convincing case for becoming a dancer. She is beautiful but lonely, well-meaning but ditzy—a classic dancer archetype. A shadowy hit man is hiding in the hotel across the street from the Iguana. Anonymously, he sends her mysterious gifts. When he finally reveals himself, he hands her an enormous stack of cash and disappears forever. This still hasn’t happened to me, but I’m keeping my fingers crossed.