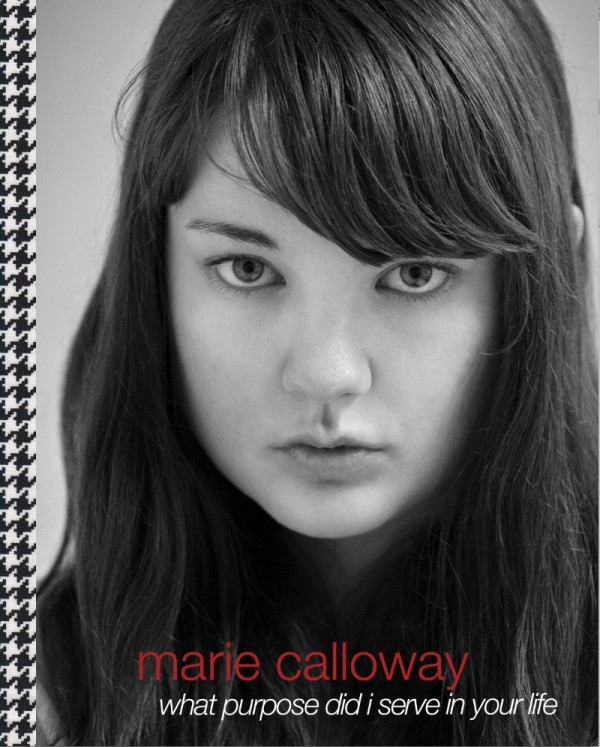

what purpose did i serve in your life (2013)

Prior to the publication of her debut novel, Marie Calloway was best known for the stories “Adrien Brody” and “Jeremy Lin.” There’s been a lot of commentary on the sexual themes in Calloway’s text, but no discussion by sex workers of Calloway’s treatment of her month escorting in London. Charlotte Shane and Caty Simon rushed to fill that void.

Prior to the publication of her debut novel, Marie Calloway was best known for the stories “Adrien Brody” and “Jeremy Lin.” There’s been a lot of commentary on the sexual themes in Calloway’s text, but no discussion by sex workers of Calloway’s treatment of her month escorting in London. Charlotte Shane and Caty Simon rushed to fill that void.

Caty: I guess I should start with full disclosure: I have chatted a bit over the past few months with Marie Calloway on the internet and she seems to be really sweet for a literary enfant terrible. But I didn’t know her from Adam when I first read her work in 2011.

Charlotte: I feel strangely protective of her in spite of never having met or corresponded with her. So it’s good to air out our biases.

Caty: I’d like to focus on the parts of her book examining sex work, because otherwise we could be here all day having the same debate that’s consumed the rest of the media about whether she’s a worthless narcissist whose very existence is endemic of essential problems with confessional writing, women and sex, and internet culture, or whether she’s a brave, feminist descendant of Bataille and Jean Rhys, who galvanizes strong responses from her readers because people are uncomfortable with her brilliance and…blah blah blah, you know where this is going.

Charlotte: Right, we’ll stay limited to T&S relevant moments.