Exotic Cancer is a 24-year-old stripper who has been dancing for four years down under in Melbourne, Australia. Since just before the start of 2018, her Instagram account has amassed a respectable fifty thousand-plus followers—many of whom are strippers that delight in her Easter Egg-colored snapshots of the minutiae of work.

Category: Art

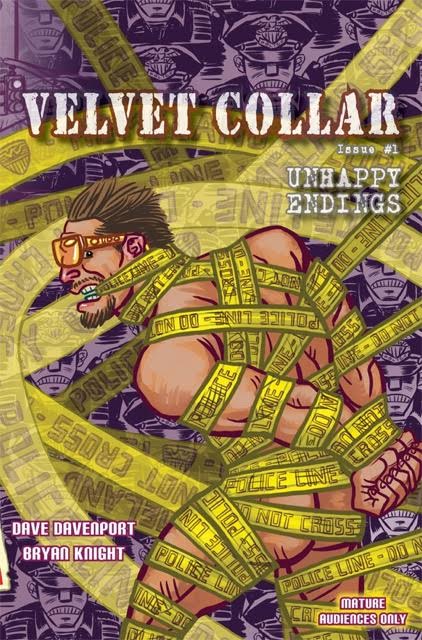

Velvet Collar, The Rentboy Raid Inspired Comic Book

Velvet Collar is a comic book series written and produced by worker Bryan Knight and drawn by queer comic artist Dave Davenport. It depicts the lives of five male sex workers. In the course of the series’ narrative, an escort listing service is shut down by the feds—a thinly-veiled representation of the Rentboy raid and… Continue reading Velvet Collar, The Rentboy Raid Inspired Comic Book

YER ART SUX: London Frieze 2017’s “Sex Work: Feminist Art & Radical Politics”

This year’s London Frieze art festival included an exhibit called Sex Work, a retrospective on the first wave of feminist art. “Your Art (Probably) Sux!” cried sex workers, upon realizing that the only one of us formally involved was an anonymous porn actress’ cropped pussy lips in a photo. But to be fair, we hadn’t even… Continue reading YER ART SUX: London Frieze 2017’s “Sex Work: Feminist Art & Radical Politics”

What Does Amalia Ulman’s Instagram Art Mean for Sex Workers?

‘Up-and-coming’ no longer describes Argentine-born Amalia Ulman. Her recent work– a secret Instagram photo series mimicking the online persona of an L.A. sugar baby–made some huge waves. Ulman is quickly gaining ground as an artist whose accomplishments extend well beyond speaking at the respected Swiss Institute and showing at Frieze and the 9th Berlin Biennale.… Continue reading What Does Amalia Ulman’s Instagram Art Mean for Sex Workers?

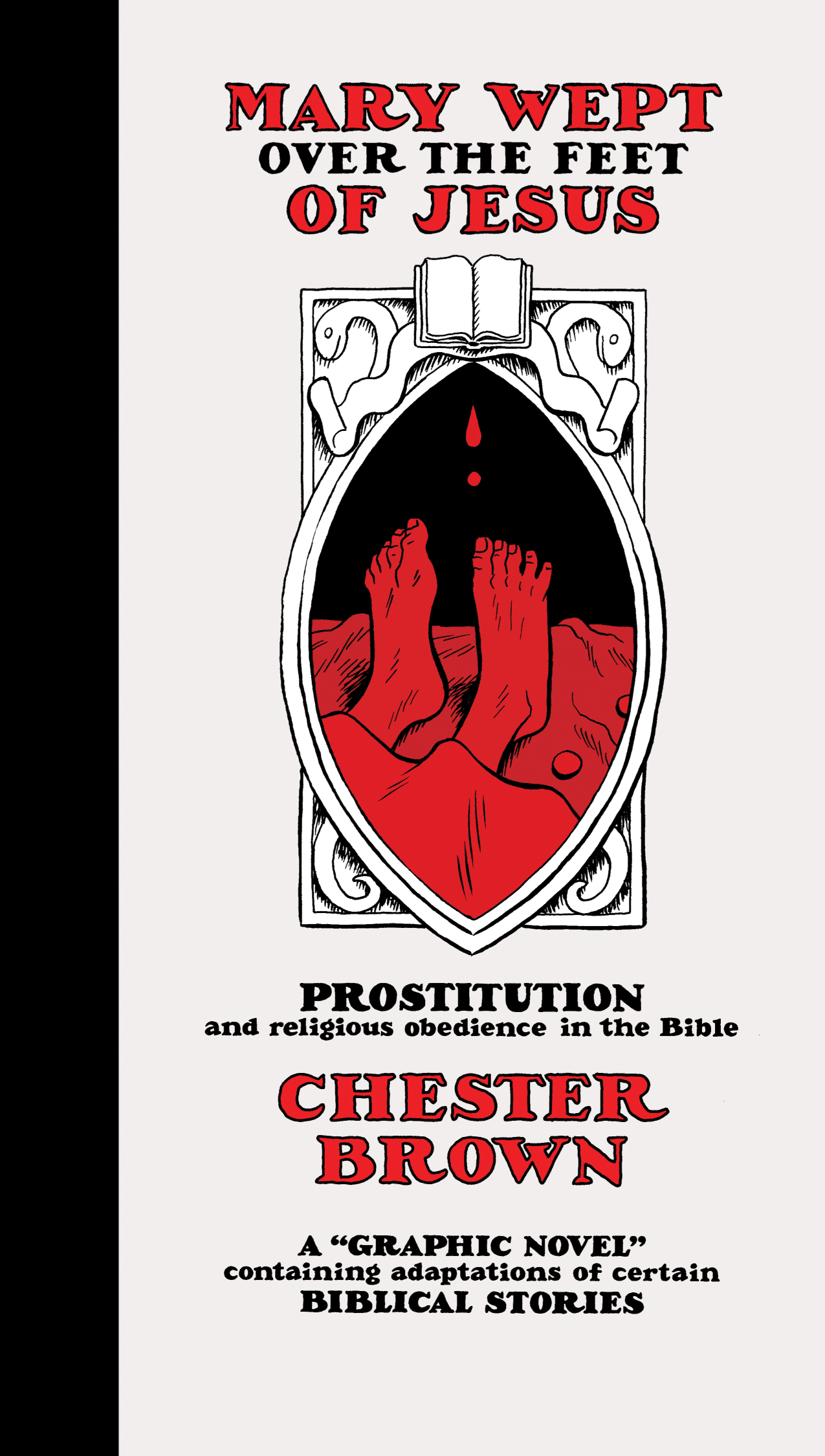

Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus (2016)

Canadian comic artist Chester Brown is probably the most well-known punter-writer our there. His latest, Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus: Prostitution And Religious Obedience In The Bible, is an analysis of the Bible as a graphic novel. (Maybe Brown likes illustration because most clients need pictures in their books.) This review of his newly… Continue reading Mary Wept Over The Feet of Jesus (2016)