This Wednesday, December 17th is the International Day To End Violence Against Sex Workers. You can read about its history here. We’ve gathered a list of U.S.-based events for our readers. Here is the list maintained by SWOP. Here’s a list for events in Europe and Central Asia. This list is organized alphabetically by city.… Continue reading December 17th: U.S. Events For International Day To End Violence Against Sex Workers

Category: Activism

Learn Human Trafficking From Home

Have you ever wondered what’s taught in university social work classes about sex trafficking? Several sex worker activists recently decided to go forth and find out by taking the online Human Trafficking course offered by Ohio State University’s Social Work program through Coursera, an education platform that partners with universities to offer online classes. Course… Continue reading Learn Human Trafficking From Home

PrEP: What It Is and How Sex Workers Can Use It

Lindsay Roth cowrote this post with sex worker ally and colleague Cassie Warren. Roth and Warren work together at PxROAR (Research, Outreach, Advocacy, and Representation), a program for community activists which offers training and support around biomedical HIV prevention research and advocacy. Readers can contact them with questions about PrEP at lindsay@swopusa.org and cassandra.r.warren@gmail.com. So… Continue reading PrEP: What It Is and How Sex Workers Can Use It

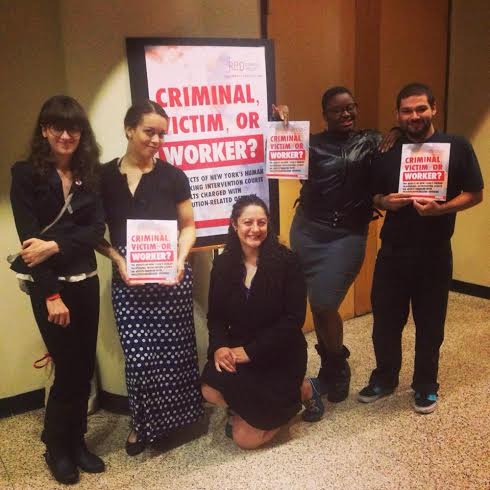

So These Sex Workers Walk Into A Human Trafficking Conference: Red Umbrella Project at the Toledo International Human Trafficking Conference

When I accepted the chance to go the International Human Trafficking, Prostitution, and Sex Work Conference in Toledo, Ohio, I wasn’t sure what to expect. The organization I work for, Red Umbrella Project, attended the conference to present our report on New York’s new Human Trafficking Intervention Courts. Just the fact that they accepted us—a… Continue reading So These Sex Workers Walk Into A Human Trafficking Conference: Red Umbrella Project at the Toledo International Human Trafficking Conference

Still Learning: On Writing As A Privileged Sex Worker

I work as a writer and a pro-domme. For me, the first stems from the second; the financial independence I earned from my pro-domming gave me the confidence and clarity to think and write. In my writing, I am out as a sex worker. My byline is a name, Margaret Corvid, that I consciously link… Continue reading Still Learning: On Writing As A Privileged Sex Worker