Meg Munoz became an escort at age 18, and had a relatively good experience working. She then took a break from the business for two years. Some time after her return to the work in order to pay for college, a close friend turned on her, blackmailing her and forcing her to turn over all… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Meg Vallee Munoz on Compassion, Coercion, and Complexity

Category: Activism

Nothing Scarier Than A Black Trans Woman With A Degree: An Interview With Monica Jones

In May 2013, sex worker and trans rights activist and Arizona State University social work student Monica Jones was charged with “manifestation of prostitution” in Phoenix after accepting a ride from an undercover cop. Her arrest ignited a firestorm of protest against Project ROSE, a prostitution arrest diversion program run by the ASU School of Social Work and the Phoenix… Continue reading Nothing Scarier Than A Black Trans Woman With A Degree: An Interview With Monica Jones

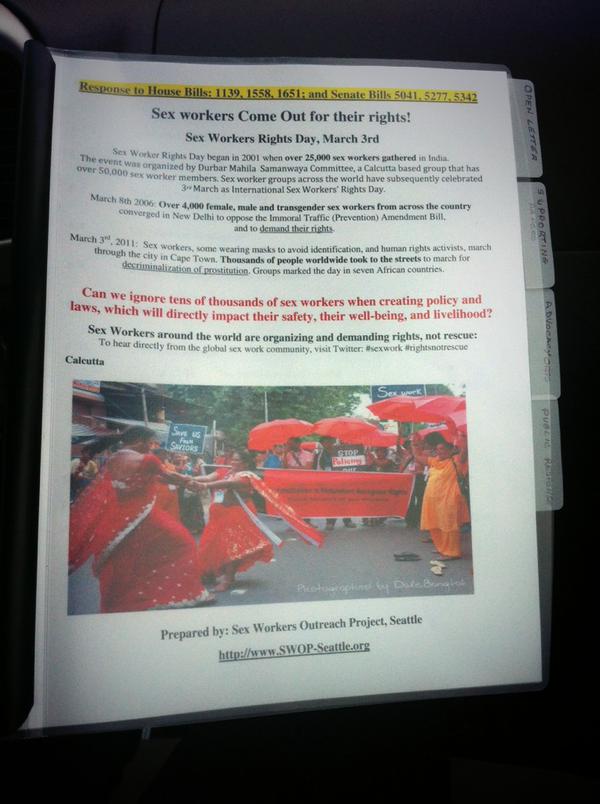

SWOP-Seattle Battles Washington Legislation

The Seattle City Council’s unanimous vote to change the legal terminology for buying sexual services from “patronizing a prostitute” to “sexual exploitation” is an example of the limits of the city’s politically progressive character. Seattle’s progressive leaders think it’s their mission to perpetuate the idea that sex workers are victims who need rescuing and eradicate… Continue reading SWOP-Seattle Battles Washington Legislation

In Memoriam: 2014 Victims of Violence

Jessica Revelee Maria Duque-Tunjano Jarrae Nikole Estepp Amanda Jane Quirk Martha Anaya Josephine Vargas Kianna Jackson Andrea Cristina Zamfir Richele Bear Sarah June Douglas Unknown Mariana Popa Margeaux Greenwald Angelia Mangum Tjhisha Ball Angela Rabotte Shantell Rivka Holden Unknown Kourtney Krista Dawson Tina Fontaine Cassandra Lynn Ferencak Schumacher Jennifer Laude Sueselbeck Jennifer Hedges Mayang Prasetyo… Continue reading In Memoriam: 2014 Victims of Violence

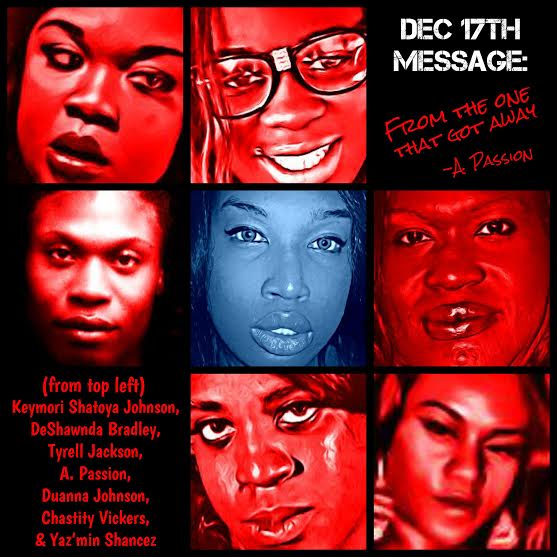

One Black Trans Sex Worker’s December 17th

On December 17th, we reflect on the overwhelming reports of violence against sex workers and put together plans of action to rise above it. We experience violence at the hands of law enforcement, clients, pimps and abusive partners, and each other. Though I have never found value in comparing suffering woe for woe, it is… Continue reading One Black Trans Sex Worker’s December 17th