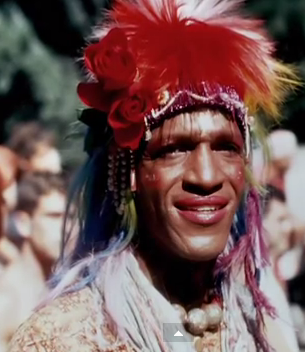

Like many of my LGBT peers and allies, I am grateful for the contributions made before and for the possibilities ahead. This summer, the Supreme Court acknowledged the humanity of LGBT individuals. And one of our pinnacle liberation symbols, New York City’s Stonewall Inn, the site of the 1969 Stonewall riots, was made a national… Continue reading How Sex Work Got Us This Far In Gay Liberation

Category: Activism

Activist Spotlight: Derek Demeri on the United Nations and Universal Rights

On May 11th, American sex workers’ rights activists Monica Jones and Derek Demeri met with the United Nations’ Human Rights Council in Geneva to advocate for protections for sex workers, in preparation for the Council’s quadrennial Universal Period Review of the US’ human rights record that same day. The following interview was conducted with Demeri,… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Derek Demeri on the United Nations and Universal Rights

The Amsterdam Window Protest: The War Continues

On April 9th, over 200 Amsterdam sex workers and their supporters protested the closing of legal sex businesses in the Red Light District by the city council. The demonstration consisted of a march from the Amsterdam Red Light District to city hall, where the protesters handed a letter to the mayor demanding the reopening of… Continue reading The Amsterdam Window Protest: The War Continues

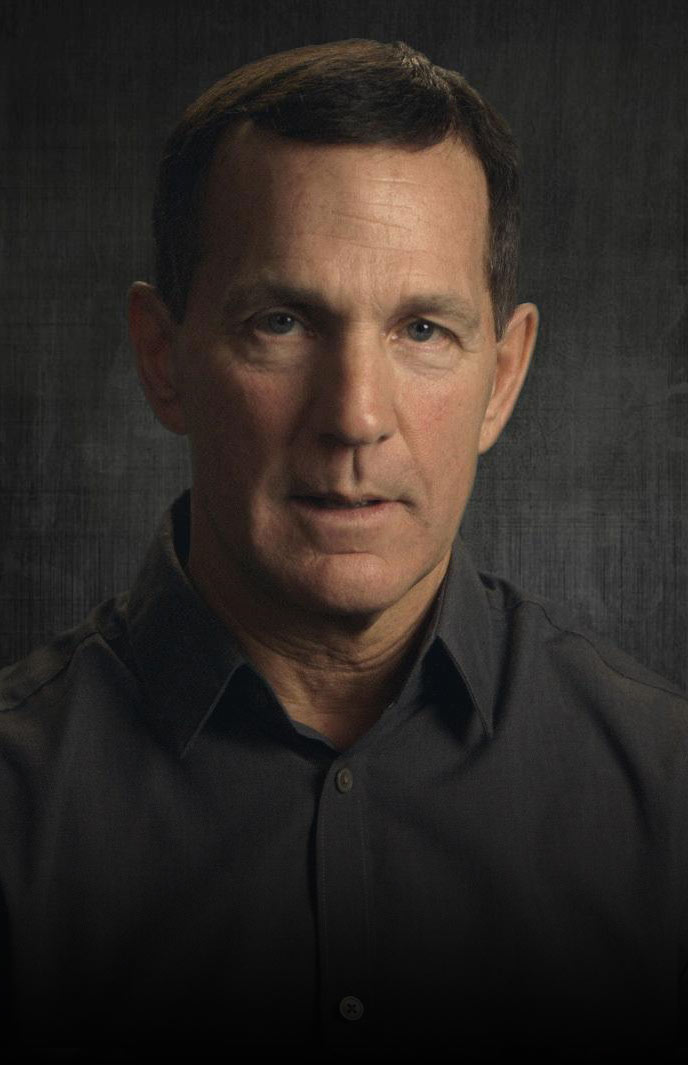

Did 8 Minutes Lie to Sex Workers?

UPDATE 5/1/15 Kamylla’s GoFundMe was taken offline and replaced with a Tilt fundraiser, which has also now been closed down. We will update if we hear news of another fundraising effort. 5/3/15 Here’s an updated fundraiser link. There’s been no shortage of coverage of A&E’s 8 Minutes, the ostensible reality show in which cop-turned-pastor Kevin… Continue reading Did 8 Minutes Lie to Sex Workers?

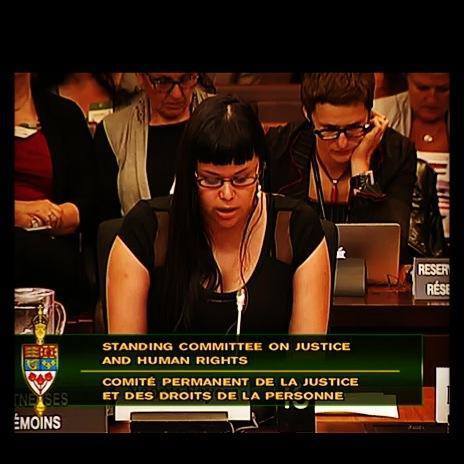

Testifying In Vain

When I woke up in Ottawa back in July 2014 after flying in from out west, there was a huge knot in my stomach. I did not want to go to the morning hearings on C-36, the anti-prostitution bill proposed in response to the Bedford decision that had invalidated three sections of Canada’s prostitution laws. But… Continue reading Testifying In Vain