‘Up-and-coming’ no longer describes Argentine-born Amalia Ulman. Her recent work– a secret Instagram photo series mimicking the online persona of an L.A. sugar baby–made some huge waves. Ulman is quickly gaining ground as an artist whose accomplishments extend well beyond speaking at the respected Swiss Institute and showing at Frieze and the 9th Berlin Biennale. Her recent viral success is due in no small part to the enduring cultural fascination with—and disdain for— sex workers. It just so happens that she used to be one herself.

Even though she was never without basic needs growing up in a working class family, Ulman found herself struggling later in life to afford food and winter clothing while making art in London, England.

“Once I had to steal a coat from a store,” she says of a time when she was also financially supporting her mother, “and for me it was the most demeaning thing I’ve had to do in my life. It was out of necessity and not just for fun or the thrill. It changes things a lot when you actually need it.”

Financial hardships aside, Ulman had to balance the time demands of artistic production: “Sadly, most people don’t really understand that the process of making art requires lots of free time. That’s why, especially now that the economy is so bad in general, it’s just full of rich kids, because they’re the only ones who can go a month without really doing anything. Because that’s how making art works.”

Moreover, Ulman was resistant to the social expectation that a young woman should be spending her time finding a husband. She was keenly aware that if she charged for that same romantic experience she didn’t want personally, she could make both time and money for herself:

“Instead of having to perform heteronormativity all night, like going on dates with random dudes, for free, I was like, ‘Well, I’ll just do that for money.’ For me, [sex work] wasn’t like a dark thing to do, or an empowering thing to do either. I was just buying time for myself to think. I had retail jobs in the past where I had a 9-to-5, plus transportation of two hours in the middle of the snow, and I couldn’t think. I would rather I monetized on my body, which I was already doing in a way because that’s how the art world was working for me…even if I didn’t want to, I was being objectified as a young female artist and most of the attention I was getting was from older men in the art world. It was very objectifying.”

Imagine this encounter: An older man invites a younger woman to a private room in Manhattan. Once there, he offers her money, sensually feeds her finger-foods, and grabs her ass as she leaves. It seems par for the course for any escort providing an outcall, but this is what happened to Ulman during a formal interview with a representative of an admired art magazine, not with a former client. This is reality in an industry with an ingrained culture of quid-pro-quo “mentorship.”

“It was one of the most horrible experiences ever because it took me by surprise,” Ulman recalls. “The guy didn’t know anything about my work; he started acting like a sugar daddy.”

“Oh, I want to make sure you live off your work,” her interviewer said, even though she had been living off of her work successfully as an artist for quite some time. Then he suggestively asked her, “Do you want a walnut?”. Confused, she replied with a shaky “OK.” Finally, he told her, “Close your eyes, I’ll feed you.” And this was a staff member of one of the biggest art magazines out there.

Just as Ulman’s art world experiences have included incidences of abuse, so have some of her sessions as a sex worker who advertised mainly on Craigslist.

Ulman recounts, “My first experience–and I’m glad I had more experience than that because if that was the only one I had, my view on sex work would be totally different. It would just be like the ‘privileged white girl’ experience of sex work, basically. Because the first was amazing. The guy was hot, it was in a nice hotel in London, and he gave me a lot of money. It was easy. It was great.”

Her next sex work experience contrasted sharply with this one: a long getaway with a violent client, high on speed, forcing sex and insisting that he didn’t need to pay her for her time. After that, a group of guys requested her presence in a parking lot to celebrate a birthday with triple penetration:

“I stopped and I thought about it: One hole… two holes…three holes? I don’t think my body is prepared! But the funny thing is that I really considered it because I had to pay rent.”

The scenario was well outside of Ulman’s emotional and physical comfort zone. She regretfully declined the invitation, lamenting the lost income of 600 pounds, a rate well above what the British government was giving her on the dole.

In one instance, Ulman was lucky enough to be able to afford some revenge. When the client who abused her during their previous vacation asked her to join him for a second trip, she said yes–then traveled from London to Paris with the sole purpose of slapping him in the face.

Despite the catharsis she enjoyed in this moment of retribution, Ulman reflected on her vulnerability during this assignation:

“What happened to me when I had to go on this trip, who do I complain to? There’s no way I can do anything. If you’re a prostitute [cops] are like, ‘Isn’t that what you do? ’ ”

In a world where the assaults of sex workers go unnoticed, it goes without saying that the intricate labor behind their sexual and emotional performances is not considered either. This is why Ulman’s Instagram piece harbors interesting potential for sex worker rights politics.

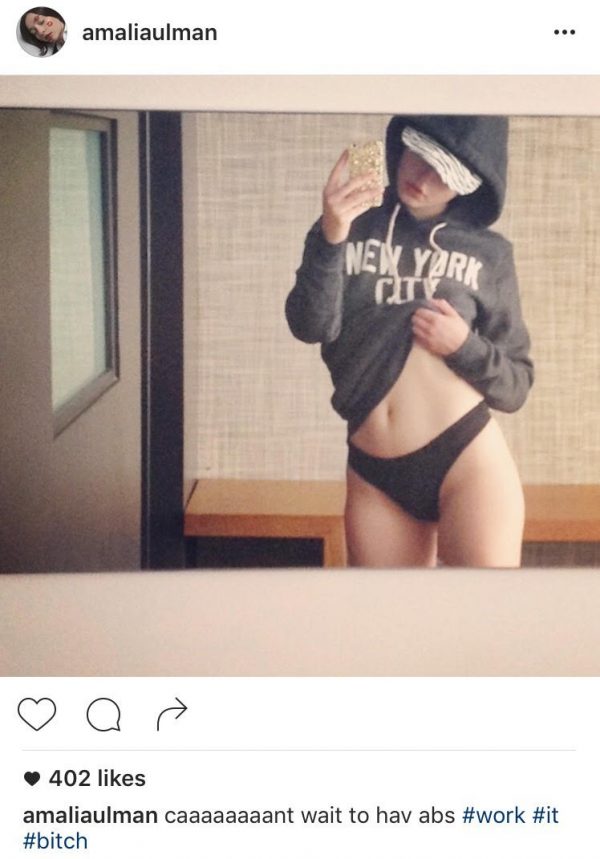

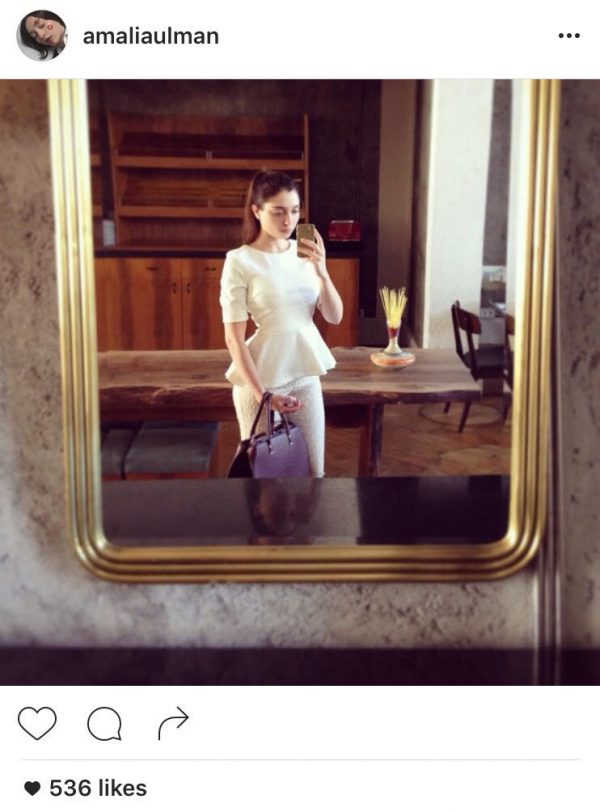

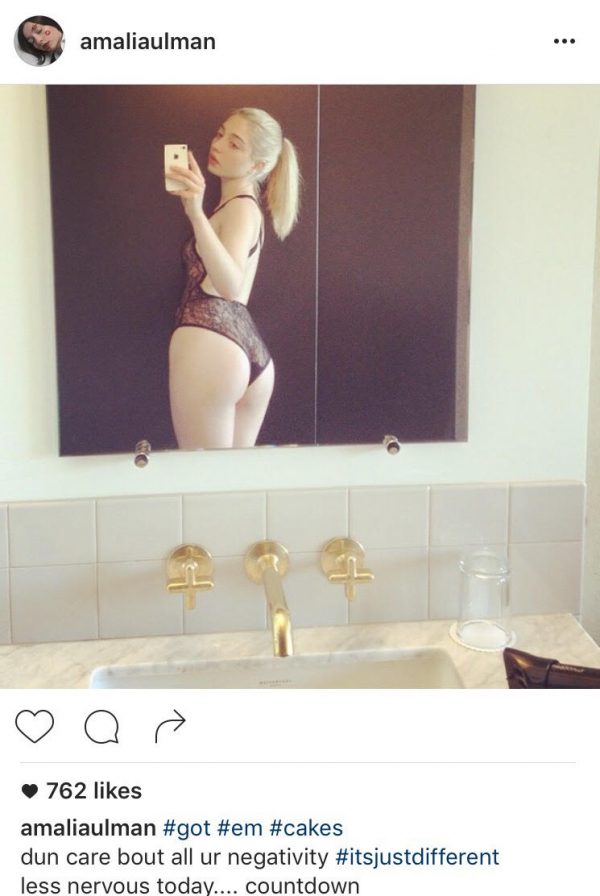

Excellences and Perfections was a carefully choreographed performance consisting of 175 sexy selfies and luxury lifestyle photos that appeared to document Ulman’s new life in Los Angeles, but there was a twist: Nobody in her life knew it was an art piece rather than an unmediated digital diary. Overnight, the artist’s social media presence transformed from edgy art student to coiffed internet it-girl. She depicted increasingly materialistic scenes of a call girl in the city, like one of a pink Agent Provocateur box (a gift from a man, perhaps: “ #work#it#bitch”), followed by the requisite semi-nude bathroom selfie in a thong bodysuit which every escort is intimately familiar with (“#got#em#cakes”). The Instagram story climaxed with an apparent tragic collapse into drugs and depression.

As her feed began to fill with these photos, images The Telegraph has since described as “mindless” and “banal,” some folks got worried. Ulman’s gallerists even warned her that her new online image could ruin her budding career. Finally, her Instagram scenes depicted a period of pious rebirth which saw her finding a handsome boyfriend, reconnecting with her family, and having brunch a lot. Tons of brunch (“#god#loves#you”).

If the linear evolution of her character sounds like every cliché representation of a sex worker you’ve ever seen, that’s because that’s what it was meant to be.

“It needed to be believable, and not be too suspect,” Ulman explained. “It was the first time for me working with this medium, and I felt that for people to follow that narrative it had to be such a mainstream narrative that people would understand it without giving them too much information.”

The narrative of the “fallen woman”—her moral failure and subsequent public atonement—is such a well-established trope that it caused very little suspicion in her unknowing audience. In fact, when Ulman’s staged apology photos were posted nearing the end of her performance, her online social world was eager to forgive her for her perceived immoralities. They had become intimately involved in her rise and fall as silent, if entertained, bystanders.

The media, for whom sex predictably sells, also played its role just as seamlessly as her old high school friends and art world fans did online:

“It surprised me how straightforward and easy it became [to convince the public],” Ulman said. “Because that was the point! It wasn’t like I was an outsider artist. No. I was respected by museums. I was doing shows. And the fact that the press just looks at the work itself, it’s exactly what I was trying to say. You’re promoting this work because it has photos of a woman in it, showing her ass, of course you’re going to put it in the Daily Mail.”

“No one said anything,” she goes on,” they were just enjoying the destruction and that is fucked up. How our society lives off of these female disgraces, like the Amanda Bynes, instead of saying, ‘you need help’ or ‘do you need some time to rest?’ For me, that was the worst. That was creepy.”

Ulman’s piece was intended to be a damning indictment of the sexist hypocrisy of social media. But her critique went beyond that to the systemic concept of personal branding that civilians engage in just as much as sex professionals whose marketing extends to these interactive public forums do.

Before beginning her Instagram project, the artist was skeptical of the way she got “drunk off likes” on her personal account:“Our society is becoming so image based when there is so much more to human experience. Like real interactions, smells, memories, there is so much stuff going on that people are neglecting for a flat image…a flat image of success.”

So is the social media identity trap completely irredeemable? Ulman actually argues for its potential, but only if one doesn’t take it too seriously. And who has more fun spoofing the internet than sex workers do? If the mainstream’s rush to the flawless Instagrammable life is the problem, the clandestine and over-the-top persona of a sex worker online might be the solution.

Because when civilian women go blonde, hooker hair is bleached blonder. If suburban wives are getting breast implants, stripper boobs are bigger. Unlike the everyday Instagram gal’s internet presence, sex worker Twitters aren’t a subtle manipulation of our everyday lives, they are dramatic reimaginations of the public/private divide. Rather than the “flat image of success,” sex workers skillfully create dynamic characters.

While Wikipedia is quick to mention Ulman’s sex work history in the first paragraph of her biography, most critiques of her work have ignored those themes and glossed over her past. This seems odd considering that the artist was more than ready to open up about her graphic stories and salacious sexual anecdotes. After all, ‘sex sells’, right?

When asked if she ever worried about being outed–many in her position might lose jobs, children, or family ties if news of their secret life went public–Ulman seemed surprisingly unphased. Her family situation, she detailed, wasn’t at significant risk. Her mother was far away and she wasn’t too close with other family members. Her friends were broke too, so they were in the same boat.

But what about her burgeoning career in ritzy art circles? Didn’t she stand to suffer from the same whore stigma that’s ruined so many lives (see Suzy Favor Hamilton) ? To the contrary. It would seem that in today’s art world, one Ulman describes as more overrun by trust fund babies than ever, a scandalizing backstory is as valuable as a daddy’s Black Amex. But could just any promising artist survive accusations of paid back-alley triple penetration and live to tell the tale at the Gagosian? Or is that an honor reserved for the white, marriageable, and delicately featured among us? Time will tell how news of Ulman’s exploits impact her career–and how similar rumors will impact her colleagues of differing race, sexuality, and gender identity. Nonetheless, it’s refreshing to witness how, in true hustler fashion, Ulman is attempting to turn a potentially problematic past into gold and succeeding.

As the dust settles, Excellences and Perfections can offer some new perspectives on the gendered impacts of social media if viewed through the eyes of sex workers themselves: some women are tired of doing all this performative labour for free. Sex workers are the women who are not only surviving but thriving in a toxic culture by monetizing the “excellences and perfections” society demands of them, and they are extremely accomplished at shaping exactly how that looks, frame-to-frame.

I’m not convinced anyone needs to steal a coat in the UK, where there are charity shops a plenty with cheap, if unfashionable, coats to be had for a very modest sum. That is rather over egging the pudding.