I usually regret the rare moments in which I’m prevailed on to cut whorephobes a break. My empathetic nature is almost always taken advantage of in these instances and I’m left feeling as if I’ve been had. As compensation, I exude coolness in interactions with potential whorephobes. It’s come to be the most significant way I protect intimacy and privacy—the first casualties of publicly decrying the treatment of sex workers. So it is with great delicacy that I attempt compassion here in my review of Ryan Roenfeld’s Tin Horn Gamblers and Dirty Prostitutes: Vice in 19th Century Council Bluffs.

I usually regret the rare moments in which I’m prevailed on to cut whorephobes a break. My empathetic nature is almost always taken advantage of in these instances and I’m left feeling as if I’ve been had. As compensation, I exude coolness in interactions with potential whorephobes. It’s come to be the most significant way I protect intimacy and privacy—the first casualties of publicly decrying the treatment of sex workers. So it is with great delicacy that I attempt compassion here in my review of Ryan Roenfeld’s Tin Horn Gamblers and Dirty Prostitutes: Vice in 19th Century Council Bluffs.

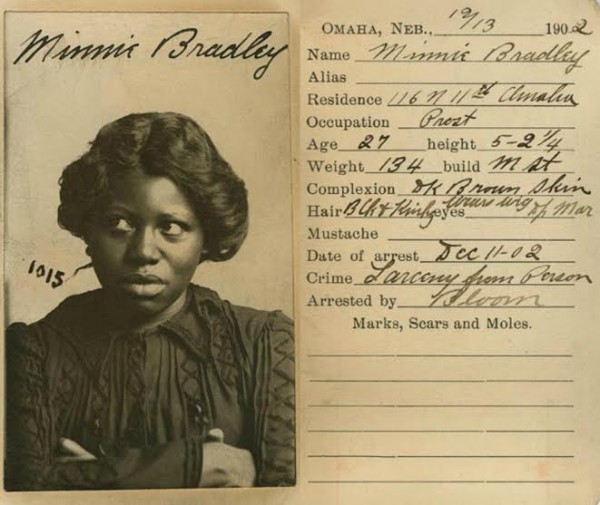

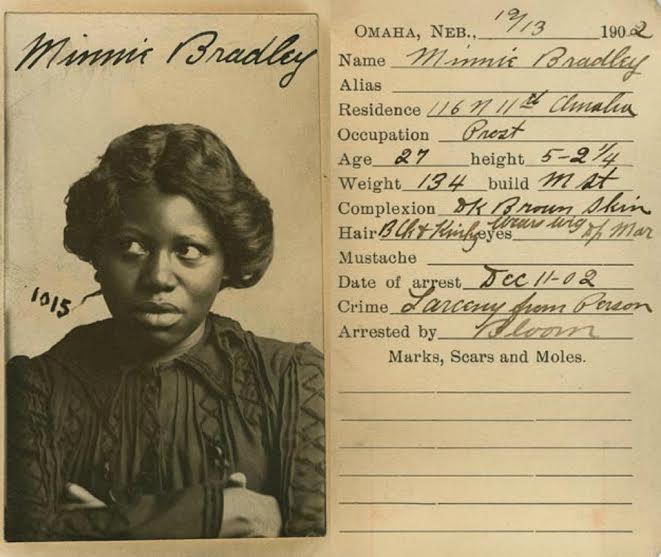

I picked up THGDP because I am myself a product of the vast prairie at the heart of the Bible Belt. I grew up in Omaha, NE, a sort of twin city to Council Bluffs, the city of Roenfeld’s historical analysis. I began my sex work career in these cities, too, almost a decade ago. Needless to say, I couldn’t wait to read all about my “dirty” sisters in vice, my lewd and despicable ancestors. I must sadly report, though, that the heroic and counter-cultural debauchery of my sisters and brothers are only briefly alluded to in the thin pages of THGDP, their humanity watered down to arrest records and salacious anecdote. Big surprise.

First, a brief note on the word “dirty,” as the title so lovingly refers to us. At one point in my life or another, I’ve been one or more of the following: a dirty hippie, a dirty bum, a dirty lesbian, a dirty heathen, a dirty drug user, and, of course, a dirty prostitute. I’m clearly a connoisseur of the unclean. It’s worth mentioning, too, that somehow the adjective “dirty” has always stung more than the noun following it, namely because “dirty” conjures up specific, visceral images about the body, about my body. I’m not the first to point out that images of perceived dirtiness have historically invoked distinctions between good bodies and bad ones. I guess I just had higher expectations for someone who calls himself a historian.

THGDP, a program presented to the Pottwattamie County Genealogical Society and sold on Amazon as a small book for nine bucks, uses articles from The Daily Nonpareil, Southwest Iowa’s daily newspaper for more than a century, to outline the history of vice there. As Roenfeld states in the introduction, his analytical eye is focused on “…a bawdy era when the city ran wide open with sins of all sorts that proved a playground for some of America’s most notorious confidence men.” The “dirty prostitutes” are but salacious accessories to the story and not worth mentioning in the introduction, apparently.

Roenfeld details the rise and fall of gambling houses and “houses of ill fame” in the late 19th century. Council Bluffs, or Kanesville, as the city was called then, became a pit stop for folks en route to California’s gold rush. Quickly becoming “rife with the sinful life,” the city prompted one passerby to claim that it was “the poorest, meanest, dirty hole [he] ever saw…” Houses of ill fame (does anyone else love this description as much as I do?), though technically illegal, provided the economic foundation upon which the city grew from 2,000 residents in 1860 to 8,000 in 1867. With $10-$20 fines per “lady of the night,” “dirty prostitutes” became ready suppliers of municipal revenue. And though the city enjoyed its new fat pocketbooks, “whorehouses” continued to be looked upon as “disgraceful” and as a “growing evil…” wherein (gasp, grip pearls) women were observably drunk. One such “fallen woman” was even observed to have drunkenly shot a man “in a delicate, but not dangerous part of the body.” This nameless ghost, clearly used as titillating, comic relief in Roenfeld’s account of history, will forever be my hero.

Despite this book being the admirable attempts of what appears to be a novice writer, it still reads as an exercise in sexism and whorephobia. When painting portraits of so called “tin horn gamblers”—the male protagonists of this historical narrative—Roenfeld takes liberties with their complexity, describing one, for example, as “a medium-sized, chicken-headed, tow-haired sort of a man with mild blue eyes, and a mouth nearly from ear to ear, who walked with a shuffling, half-apologetic sort of a gait, and who, when his countenance was in repose, resembled an idiot.” Women—who only exist here as “dirty prostitutes”—are one-dimensional and described only in relation to men: for example, as an “affectionate wife,” a “fallen daughter,” and a “favored girl.” Following these shallow depictions is ample attention towards hearsay accounts of abuse: the nameless, neglected orphan working in “Rotten Row,” the city’s most infamous red light district, Belle Clover’s (spelled both “Bell” and “Belle” throughout the text) “long-term abusive relationship with [her husband],” Ms. Griffin, a madam, who’d been “driven from home by the abusiveness of her father,” and Stella Long, also a madam, who, according to Roenfeld’s uncited source, abused the women who worked for her. Stipped of their complicated humanity, the women in THGDP are merely the victimized playthings of male historical characters and, of course, of the historian himself.

What I find compelling about this little book are the newspaper quotes that evoke some pretty serious imagery of the sex worker as desperate, abused, diseased, and, well, drunk. It’s tragic and yet, strangely validating to trace the discourse of anti-trafficking rhetoric back to beliefs about prostitution and women more generally at the turn of the century. The local newspaper from which Roenfeld derives the majority of his quotes reads like a gossip column partitioning the good girls from the bad:”…another fallen woman [has abandoned] all hope of reclamation and of virtue for a life of infamy and degradation.” Cultural obsession with the piety of young girls is still evident today in anti-prostitution rhetoric disguised as anti-trafficking philanthropy. Except, the trafficked girl has replaced the fallen woman and the rescued victim has replaced the redeemed whore. We—society writ large—are actually still having the same antiquated conversations as our slave-owning, anti-suffrage predecessors.

The book is selling on Amazon you say?

Sold!