During my first few years working, I would get my hands on any stripper memoir I could read, obsessed with finding out how other women experienced this bizarre life I ‘d embarked on. I was relieved at finding how common some of my insecurities and struggles were, and occasionally disappointed to discover that none of my thoughts on the business were as original as I had hoped.

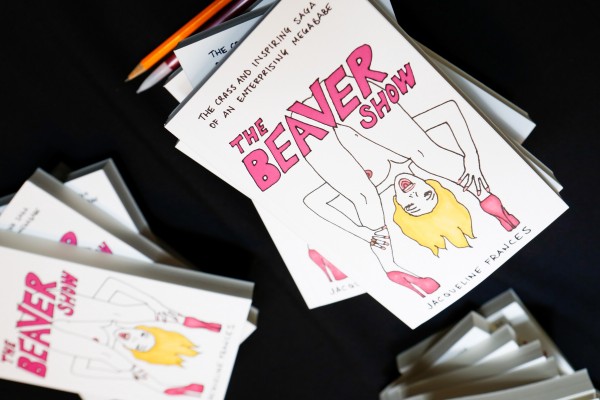

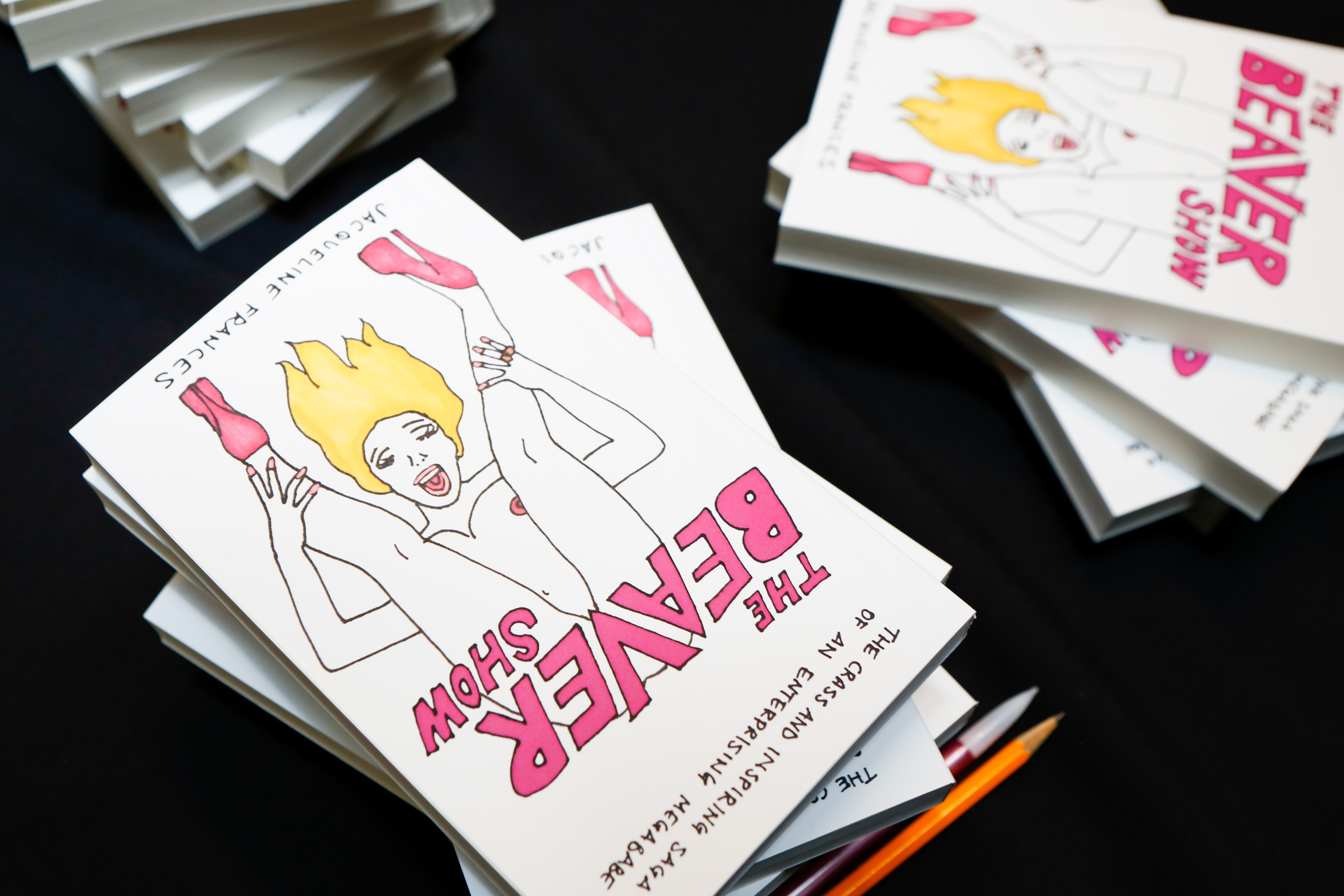

The Beaver Show, by Tits and Sass contributor and blogger Jacqueline Frances (AKA Jacq the Stripper), was a reintroduction to my love for stripper lit, and brought with it a sweet nostalgia for my fish-out-of-water feelings as a baby stripper. The book chronicles Jacq’s first days working at clubs in Australia, then follows her to stints in New York City, New Mexico, Alberta, Canada, and Myrtle Beach, S.C. Like me, Jacq goes from feeling confused, clueless, and decidedly like an imposter, to riding the high that comes with early success, to settling with the persistent irritation that I think is unavoidable after you’ve been in the business a few years. She begins the book with a short personal essay she wrote in fifth grade, where she says that her proudest moment to date is dancing onstage in cool costumes. From there, we follow her to her first day at work.

Like very other stripper memoir I’ve come across, Jacq is hilarious and colorful in her descriptions—it’s frankly pretty hard to write about our business without making fun of it. What I found unique about her, though, was her ability to describe some of the more tender moments of dancing, the more touching and painful parts that ask for a bit of sincerity in the narrative amidst the caricatures of clients and clubs. For example, a few days after starting at her very first club, a customer sits at the tip rail, gives her two dollars, and demands that she perform a pole trick:

“I’m embarrassed because I don’t know any tricks. I feel unprepared. I feel like I owe him a trick. I feel all these things because I’m a rookie stripper and it won’t take long to learn that entitled assholes abound and they are yearning to be put in their place.

But for now, I have to undergo this humiliating feeling of not being enough for this man; to feel like I have to go above and beyond the call of duty to earn his attention, approval, and laminated money.”

A lot of stripper memoirs I’ve read avoid discussing this kind of insecurity. I personally found it very familiar, particularly reflecting on my earliest days of working. I think it’s not uncommon for sex work memoirists to be unashamed in admitting their body insecurities, or their discomfort with having boundaries pushed by asshole customers. But I find this sentiment—the persistent and innate pressure some of us feel to please a total stranger, to not disappoint, to not fail, even without substantial financial reward—to be something people shy away from discussing. It was something I felt all the time, couldn’t explain, and never spoke much about. Maybe moments like this don’t match the autonomous tough girl image we all like to wear, maybe it’s too embarrassing to admit, or just not funny enough to write about in between jokes about whiskey dicks and g-strings. I was happy that Jacq chose to go there, because it’s important to show what working in the industry can do for the evolution of someone’s confidence and sense of control.

Another moment that rang true was Jacq’s early relationship with a civilian woman, which began in her first few days of dancing. Maxine, the new girlfriend, seems unbothered by Jacq’s profession, but that nonchalance comes at a price. “If Maxine is bothered by the fact that I’m secretly a stripper, it is eclipsed by the fact that I pour most of my winnings into our activity fund,” Jacq writes. “I’m too busy with my head up my naked and profit-turning ass to see that this is probably not the best foundation on which to build a healthy and lasting relationship.” Their romance is short-lived, and so Jacq doesn’t go into the ways these dynamics can develop into an abusive situation. But using sex work earnings to try to buy a partner’s respect and acceptance is something I’ve done in my own life and seen many of my friends go through. Yet I haven’t read about it much in other strippers’ memoirs.

The Beaver Show, as the title suggests, is far from all heavy, though. The majority of the book is hilarious and fun—that’s just not what makes it unique in the genre. I appreciated how real and honest the writing was. Jacq shied away from the stereotype of a girl who can’t stand her clients, is in it just for cash and flexible hours, and finds nothing else redeeming about the work. Toward the end of the book, one of her colleagues finds herself delighted that a customer dominated her during a Champagne Room session. Jacq then offers readers “stripper tip #42, which is: “Stripping isn’t just about catering to other people’s desires. It’s also about discovering the extent of yours.” She has a few fleeting crushes on clients (again, not uncommon, especially when you’re starting out), and finds herself sympathizing with them in ways she doesn’t expect. One of my favorite passages, a moment that made the whole book worth reading, happens early on when she’s dancing in Melbourne. She finds herself reflecting on the way the work has changed her, that she can vacillate between being bitter and annoyed to having deep empathy for some of the lonely guys who wander through the club doors:

“None of my colleagues care to dish about the moments of compassion. It seems defeatist to discuss enjoying an aspect of the job that extends beyond the pride of extortion. We all ‘like the money,’ but for some reason it’s just not socially acceptable to talk about what else we like about it. The predominant ethos of the working girl is Hate Men/Love Money. And sometimes I sincerely share this feeling, I really do. Most men are fucking pigs—snorting, drooling, stinky stupid, aggressive fucking pigs. And sometimes they are sad, lonely and shy.”

This was especially poignant for me, as I remember even telling people in my first year of working how much I hated men, and how taking their money was how I felt I got even, knowing even as I said it that it was partly a lie. Dating while working encouraged this kind of talk even more, as it was sometimes impossible for my partners to accept that I often liked my work and enjoyed moments of emotional intimacy with people, enjoyed feeling like I was making their day better. It’s easier, and often more fun, to assume the role of the sassy, heartless bitch who feels nothing for the people she sees and has complete control over both parties’ emotions.

Discussing points like these is important, both in the interest of writing honest, emotionally profound memoirs, and in the struggle to lessen the social stigma of our work. There’s a gratification that comes with making your customer happy, whether it’s performing that cool pole trick or easing someone’s loneliness. Allowing ourselves to admit this more often will only do us good when it comes to convincing the rest of society that we’re just working people like they are.

Hey! So how do I get a copy of this book? Want to buy ASAP!!!!!

Hey, I wouldn’t mind getting this book for a friend. Amazon.ca has it listed as “temporarily out of stock” and it really doesn’t look like it will be coming in anytime soon. Any idea concerning Canadian distribution of the book?

Thank your for writing a review and helping to guide others in a way that will push the kind of writing that is needed in our community. Through my 9 years of dancing I absolutely have evolved into a “people pleaser”. I consider myself a chameleon of sorts because I read into the customer and figure out what they want out of our interaction. I take extreme pleasure and joy out of these moments and it’s something I thrive on when I’m there. When I’m home I’ll say, “I don’t want to go in…” and when I come home, I say ” I’m so glad I went in I met the most amazing person.” That amazing person and I shared something special; an exchange of desires and pleasure that had nothing to do with sex.

Thanks again for inspiring me to think about all this.

Read this as well! After 2.5 years of stripping, this renewed my enthusiasm for work and eased some lingering bitterness I was feeling that was rooted in my boredom with the job. This was the first “stripper lit” book I’ve read, and I too was (embarrassingly) shocked to find that I’ve never had an original introspective or tactical thought about stripping. It was nice to read a queer stripper’s personal history.