by Clara and Caty

[Content warning: some discussion of rape. Also, spoiler warning.]

Clara: Westworld is a science fiction western thriller created and produced by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy. JJ Abrams is also a producer, so think Jurassic Park meets Firefly with a dash of Lost. As with its predecessors—Blade Runner. Battlestar Galactica, etc—Westworld uses human-like robots to tell us a story about humanity. Questions like “How do you know you are human?” “What is consciousness?” “What are dreams?” “What are memories?” “How does does your past define you?” “What is free will?” “What is consent?” are asked but not always answered.

The titular Westworld is a Western theme park where life-like robots—”hosts”—act out stories called narratives in a controlled environment for guests of the park. The park is marketed as “life without limits.” The idea is that because the hosts are robots you can do anything you want with them and it doesn’t matter.

While not a show directly about sex work, Westworld in its over-all arc is about the push/pull of market forces between client and worker. It is also about the uprising of a group who is fed up with being used. Sex workers who have to constantly prove their humanity to society and deal with client entitlement every day might find the show reminiscent of their lives.

Caty: I would argue that this show is about sex work. It’s about a separate, disposable class of people who perform reproductive/emotional labor so that guests can enjoy their leisure. The hosts’ very lives are this labor, so they can’t even be compensated for it. And they literally have false consciousness.

As the show reminds us constantly, the hosts’ purpose is to be fucked or hurt, or at the very least to immerse the clients in a fantasy, which sounds like the sex worker job description to a T. In fact, the hosts are the ideal sex workers from a certain client perspective. They are the ultimate pro-subs, who can be beaten, stabbed, strangled, and shot, only to be refurbished, resurrected, and brought back as a clean slate in terms of both their memories and their bodies, ready to take those blows again. They are entirely “authentic,” programmed to believe that the role play they engage the guests in is what is actually happening. If the Westworld story that the guest is indulging in is that Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood), the damsel host, is in love with him, she actually is in love with him.

But what Westworld actually does best is reflect the client mentality—an Entertainment Weekly recapper quipped that the Man In Black (Ed Harris) sounds like “a dork playing Dungeons & Dragons who yells at other players for asking for a bathroom break” when he gets pissed off after some other guests refer to his work in the real world. But to me, he actually sounds like the BDSM client I used to have who would shriek “WE DON’T TALK ABOUT THE MONEY” if I ever said anything which derailed his fantasy of being a scene elder teaching eager young acolyte (unpaid) me about kink.

And who does William (Jimmi Simpson) remind us of most but a stalker regular when he turns (even more) murderous and rapacious after realizing that Dolores doesn’t remember him—that he isn’t special enough to her to override the programming that forces her to forget him after each go-round? At first, he’s a Nice Guy—that trusted reg, the one who believes Dolores is sapient and Not Like All The Other Hosts. He’s Captain-Save-A-Host! But later, after his embittered violence runs roughshod over the park for 30 years, after he assaults Dolores over and over, and then grows “tired” of her like the most jaded hobbyist, Dolores tells him, “I thought you were different, but you’re just like all the rest.”

Clara: It has sex work themes and parallels but to make it a show about sex work gives the show too much credit. But the refrain from the second episode, that “you and everyone you know were built to gratify the pleasures of the people who use your world,” was on point for me as a former brothel worker.

As a fellow member of a disposable society, I have extreme empathy for the hosts, especially the salon girl hosts. Some Westworld staff (scientists, coders, butchers) evince a palpable disdain for the hosts, but it is especially acute for the hosts that are in the salon girl narrative.

In episode two, the scientists change Maeve the madam host’s interaction feature, upping her aggression. Their reasoning is “She’s a hooker—she isn’t supposed to play coy.” Later in the season, a different Westworld staff member comments that Maeve is a “quick study of repressed fucks.”

Caty: The reason they change her interaction feature is because she’s attracting fewer customers. This early narrative about Black sex worker Maeve being in danger of being retired is very racially coded. Black sexbots are apparently less valued in this industry, just as Black human sex workers are also devalued. Maeve is in danger of being literally disposed of. The way they push up her programmed sexual aggression can also be read as racist. They turn her into the lusty Jezebel figure they expect a Black sex worker to be.

What I can’t figure out is whether this is a commentary on misogynoir or just plain old unthinking racism on the show’s part. It reminds me of how the show often seems to be attempting a critique of misogyny while actually truly reveling in its rape scenes. In this case, I don’t even think it’s that deep—the show is just as carelessly racist here as the Westworld staff are, just as neither the park’s narratives nor Westworld itself gives its Native Americans speaking parts.

Clara: I wanted to speak a bit more about upping Maeve’s aggression, and how it is perceived. When the clients she approaches after she’s adjusted recoil, we, the audience, are taught that only a certain amount of aggression is wanted, and that this level of it is not “sexy.”

We can use the theme of aggression as a jumping off point between the two main female characters, Maeve and Dolores. In the beginning, in contrast to Maeve, Dolores is shown as soft and pliable. We can take that further and reenact the Madonna/Whore trope.

This is most apparent in how both the camera and the Westworld staff treat both women’s bodies. When a robot is killed they are taken out of the park and repaired. They are often interviewed about their experience to make sure they are functioning within normal parameters. This debrief occurs with the host in the nude and the interviewer dressed.

While HBO does like its gratuitous nudity, the nudity during the interviews is mostly akin to elf nudity in Harry Potter. It is sexless, there to accentuate a power differential. The key difference between nude and naked is that “nude” implies that clothes are just not a factor, whereas “naked” implies sexuality and vulnerability.

Dolores is nude, Maeve is naked.

Maeve (Thandie Newton) has traditionally European features, just in a darker hue, to go along with a white beauty standard. She is always dressed in salon girl clothes—fishnets, purple bodice, red skirts—she is the Whore.

This dichotomy plays out in the way the camera treats them. Dolores is nude. Her interviews are done with dignity, in soft light. A cascade of soft blonde hair covers her smallish breasts while she is interviewed.

Maeve is naked. Her interviews are done in harsher light and her larger breasts and nipples are prominent.

A scientist (Elsie, played by Shannon Woodward) even kisses Maeve during the first episode while she is prone and offline. This makes it clear to the audience from the beginning that hosts are hosts—but whore hosts are still whores. This is echoed with lines such as “she is just a hooker” in later episodes.

Dolores is blonde and innocent. Dressed in a traditional Mary color (blue) she is the Madonna. Dolores’ purity is propped up by her relationships with both Teddy and William. Teddy (James Marsden) is attempting to rekindle a relationship with Dolores but has to “make things right” before they can start. This places Dolores on a pedestal—Teddy has to become a better person to win her. William also places Dolores on the same pedestal. His brother-in-law Logan (Ben Barnes), another guest, mocks him because he thinks of Dolores as a lady, not a robot.

Maeve is the first host that realizes that her world is not all that it seems. She begins to remember bits and pieces of her past narratives and the interludes between lives in which technicians perform surgery on her to refurbish her. This is purposely reminiscent of alien abduction stories.

She wakes up during a surgery and becomes cognizant of her own robot nature and that her life is being manipulated. She purposefully keeps getting killed in order to revisit the surgery table to learn more about how her world truly works. Eventually, Maeve demands that two butchers/surgeons change her settings so she can be more in control. She blackmails one and the other acquiesces.

Caty: What strikes me about these scenes is the part in which Maeve starts demanding her agency—”I know when I’m being fucked!”—only to realize that this sex worker insight is literally a part of her programming, as her own words as she speaks them appear on Felix the technician’s (Leonardo Nam’s) screen for her to read. It’s a delicious irony that the emotional labor-bot who plays the role of the veteran sex worker gets programmed with a script full of salty lines about leveraging this sort of labor.

This must be how SWERFS think of those of us they believe are in the “pimp lobby”—as ventriloquist’s dummies mouthing the industry’s lines. So I was especially gleeful about the part where she takes the reins and makes them program her to be smarter and less loyal (“my loyalty has been taken advantage of, don’t you think?”). And the way she uses the very emotional intelligence Elsie programs into her to aid her in her brothel work to manipulate the technicians into doing this in the first place. For me, this reflects the way we sex workers constantly remake ourselves to be more adaptable, how we learn to be less exploitable in very vulnerable circumstances.

Clara: This also begs the question: Can we ever gain agency from our creators? Are the masters’ tools the thing to use to dismantle the master’s house, a la Audre Lorde?

While I am excited to see a strong sex worker character, especially a woman of color, take on a prominent role, Maeve’s story arc follows the trope of the strong black woman savior. We put the person with the least social capital at the front of the picket line. A similar plot line was also used in Gotham when Black criminal leader Fish (Jada Pinkett Smith) leads folks out of the tunnels.

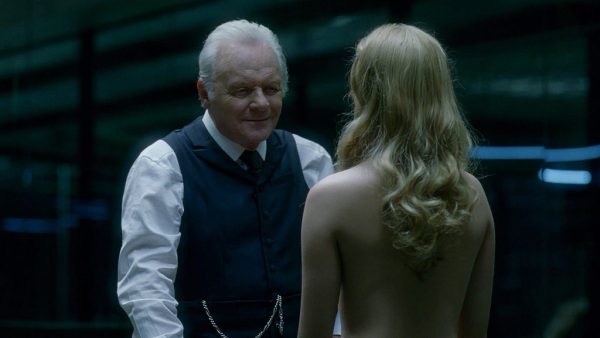

Caty: And what does it mean that Maeve is actually programmed by one of her creators to wake up during her refurbishment and thus realize the nature of her existence, and then is further programmed to lead a rebellion that actually fits creator Dr. Robert Ford’s (Anthony Hopkins) suicidal, but calculated script? It’s akin to the client impulse to enjoy and even expect a little bit of push back, as long as it’s a rebellion that he’s planned for. Ford is the same man who actually creates a black friend for himself in host Bernard (Jeffrey Wright), a mimicry of his dead partner Arnold, who had the hosts kill him because he felt that they were too self-aware for the park to be ethical.

The idea of the “reveries” haunted me, too. These are absent-minded gestures connected to very faint memories of the hosts’ past narratives, which Ford has introduced recently when the show begins. One of the brothel women, Clementine (Angela Sarafyan), demonstrates a revery in a quiet moment when she lightly brushes her hand against her collarbone. They are supposed to add to the hosts’ emotional depth. It takes a certain type of refined sadism to even think up the concept of these reveries. It reminded me of nothing so much as a client who loves the fact that his sex worker has a sad story, whether she tells it or not.

These half-memories of trauma backfire and allow many of the hosts to begin to truly remember their past narratives. Dr. Ford explains the fact that he only threw in to help the hosts gain their freedom thirty years after he opened the park by saying they had to grow up first, become human through suffering. I find this point of view reprehensible, but I do think that this part of the hosts’ story reflects how sex workers incorporate the trauma they experience into becoming better at survival.

Ford actually believes that trauma is sentience when it comes down to it, and he builds the hosts accordingly—they each also have a “cornerstone,” a memory of tragedy so essential to their identity that to remove it would be to erase the personhood of the host entirely. Since I’d argue that the hosts are stand-ins for working class women, or more specifically for sex workers, that’s very telling in how it’s reminiscent of the mainstream idea that childhood abuse is what makes sex workers who we are, or the idea that poverty is a choice, born out of a damaged psyche.

Clara: No one seems plussed by the idea of having sex with robots, or their consent level. Do robots have to be self-aware in order to consent? What level of self-awareness makes it okay? I have had long arguments well into the night with fellow Trekkies about Data’s sexuality and consent.

In Star Trek, Data, the android, has a few sexual partners. In a now famous episode, “The Naked Now,” Tasha Yar asks how “functional” Data is: he replies that he is fully functional and is programmed in many “techniques,” a wide variety of pleasuring. Is consent seen differently in this context because Data is a male? Charlotte Hale (Tessa Thompson), the board rep for the investors in the park, enjoys a male host sexually. Does the audience think of his consent or is it just the women hosts they are concerned about?

There has always been a discussion if the “love scene” in Blade Runner—in which Rachael, protagonist Deckard’s replicant love interest, runs away initially, only to have him corner her and command her to tell him to kiss her—is actually a rape scene. The film establishes that replicants have emotional lives just as humans do, after all. This is also one of the principles that Westworld is built on. The hosts not only remember what occurs throughout each narrative but also have emotional responses to it.

Unlike Blade Runner, in Westworld, the audience, but not the guests, are aware of the internal lives of the hosts. I would like to give the benefit of the doubt, hoping that one of the guests noticed that Clementine or the other hosts experienced backed-up trauma memories of their previous narratives, but perhaps I am giving too much credit to folks who spend $40,000 to visit a salon for the express purpose of fucking and killing.

The genesis of the idea of creating a female non-human entity for the purposes of love/affection can be traced back to Ovid. The hosts in Westworld, Six in Battlestar Galactica, Rachael in Blade Runner, Ava in Deux Machina, Lisa from Weird Science, et al.—are a retelling of Ovids’ Pygmalion.

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a sculptor, Pygmalion, carves a woman out of ivory. His statue is so beautiful and realistic he falls in love with it. While the translations of the texts are not clear, one can surmise that he has sexual relations with her.

The standard feminist interpretation would be that male creators have womb envy since they can not create life, but merely art. Are the hosts an amalgamation of the two?

Caty: The hosts as works of art make me think of the way we often see marginalized people’s very lives as art, to be recorded as folklore or immortalized in scenic photos. Exoticization is very much a part of the company’s modus operandi.

As Laurie Penny explained in The New Statesman last year, the fact that we feminize the non-sentient artificial intelligence we have, like Iphone’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, says a lot about the feminized status of the caretaking labor that machines do, which falls into the spectrum of the labor the hosts are doing in Westworld. She notes that the anxieties we have about artificial intelligence—are we exploiting them and what will we do if they rebel—are the same anxieties the patriarchy has always had about women. In a piece on the same theme in the Establishment, Katherine Cross reminds us that Karol Capek, who coined the term “robot” in his play R.U.R., took it from the Czech word for “slave,” and that feminized artificial intelligence is often a stand-in in our minds for a pliable, uncomplaining, perfectly efficient female service class: “The service industry, already highly feminized in both fact and conventional wisdom, is made up of people who almost never have the right to say no, and virtual assistants who simply can’t are increasingly the model of the ideal service worker.”

In sum, when we talk about robots, we’re often talking about how we feel about working-class women.

Midway through the show’s run, Molly Fitzpatrick astutely noted in Fusion that while the implication is that all the hosts in the park are available to sate the guests’ lusts, regardless of gender, besides the blink-and-you’ll-miss-him presence of one male sex worker in Logan’s group sex scene off to the side stroking his chest, overwhelmingly, it’s the women hosts we see in sexual situations. And yes, later on we see Hector tied to board member Catherine’s bed, and we even see a technician plan to rape him while he’s supposedly offline. But the interlude with Catherine seems more about how she can wield male power both in and out of the boardroom than any comment on her sexuality, and Hector wreaks bloody vengeance on the technician before any damage is actually done.

It is the women hosts who are dragged out by the hair and raped, choked to death in bed, fucked in every manner imaginable. Maybe that’s Westworld’s statement about the sexual vulnerability and exploitation of women and women sex workers, or maybe it’s about Westworld itself being a white man’s vision, his uneasiness about the potential uprising of ill-treated women sex workers. The show lacks the imagination and inclusivity—much as most political analysis about sex workers does—to account for the male and non-gender binary sex-working class.

Ultimately, I think that’s why the show has the most engaging things to say about clients—because Jonathan Nolan and his crew are much more likely to have been clients than sex workers. For example, I love how Logan interminably monologs to William about how the park changes the guests, gets its hooks into them, seduces them, reveals their true selves. He’s totally fixated on how the hosts affect them, in the same way that clients are always focused on how they feel manipulated by sex workers or libidinally emancipated or whatever—review boards contain thousands upon thousands of words of stilted prose by clients about how we make them feel. Even when William insists on Dolores’ self-awareness and she shows blatant signs of it in front of him, Logan just thinks William is that pathetic john who’s fallen in love with a prostitute, here, the pathetic man who falls in love with a robot. Logan is entirely incapable of considering how the guests affect the hosts or of conceiving of the hosts as sentient, just as most clients draw a blank when it comes to sex workers’ inner lives.

And yet, the one part Westworld nailed when it comes to the depiction of sex work was the relationship between the two brothel-working hosts, Maeve and Clementine. I loved the little details of dialogue between them, like when Maeve grouses at Clementine, telling her she’s not paid to talk, and Clementine reminds her of the primacy of emotional labor—”I’m paid when they’re grateful,” she points out, flashing the shiny coin she got the night before when a client confided in her.

And Maeve’s mournful look at Clementine when she talks about the money she sends back to her folks and her plans for life after the brothel says it all. Because Maeve knows that Clementine’s family doesn’t exist and that white-picket fence life after the brothel will never materialize for her. It’s the same look we give our co-workers when they talk about their hopeful post-sex-work plans, knowing how hard it is to get a straight job that pays a living wage, how hard it is to get a straight job and leave sex work, period. Just as Arnold and Ford’s park is built to contain the hosts and exploit their labor, so are we stuck in these lumpenproletariat lives by system-built barriers like poverty and criminalization, things we’re meant to believe are just the natural consequences of this very artificial world we’re in.

One thing that I thought while watching the show, was that however tough Maeve is, however sex worker savvy she is, her programmer had to have been savvier in order to give her that. And who is more savvy about sex work than a sex worker? I wonder who really programmed her. (Like her remark about half a fuck being worse than none at all, though that could also be just the perspective of a woman.) But my question is within the context of the show itself, not the show’s creators. In that, I agree that the show is created by clients, though I think these clients are at least as self-aware as Maeve and Dolores…light years ahead of the typical hobbyist.

About suffering…I know from my own experiences with clients that while they often imagine silly backstories for me (including tragedy), my reality punctures it for them. Very rarely can a client handle reality, regardless of whether the reality is better or worse than their fantasy. This is not a new thought, I just wanted to mention it because it ties in so well with the show and review. We all have backstories. (I’m also incredibly amused by how much attention the show pays to backstory, something I expound upon in my second book. Backstory makes the fantasy real!! Just don’t have Sizemore write it for you!)

I thoroughly enjoy the show and identify with the robot uprising, really. Some of it for reasons stated here, some of it for my own reasons. Can’t wait to see women and sex workers wreaking havoc in Season 2.

typo: ‘deux machina’ should be Ex Machina.

Nice dicussion, BTW.

Wow… I think I disagree with almost every sentence in the post, which is new.

I have been following the blog for a long time but the difference between your interpretation and mine are staggering.

I do not think either of us can be sure who is right or wrong until we sit down with the show creators and literally ask them. Based on previous shows… they are not as aware as I would like them to be… but a lot of the criticism here is… in some aspects, missing the point of the show, for me, of course.

This is simply my opinion, I am unsure if it is more or less correct considering my lack of access of sex work experience, so it is possible I see things that ring painfully trite, old and stereotyped for you, as not such. 🙂

In short, I see a wonderful play with the madonna/whore dichotomy but I have not seen the two women pitted against each other. I think the show turned the concept on its head. The nakedness was “explained” as a way to distance the people who work there and it is for both genders. And the creator, who literally rebuilt his friend, who killed himself, obviously intended to nudge the robots to reach self-awareness.

It is somewhat specified that William met Maeve 3 years ago (prior to the events of her escape) and that is when he realised that pain help them keep and build their awareness. Prior to that… ultimate nice guy I have seen on TVLand,

Ok but what about Clementine’s “I should’ve been paying him” nonsense?

I’m going to guess a male writer wrote that line.

Holy moley that was hilarious. I looked at my partner as we were watching that line and I think I almost sneezed out my cookie it was so out of place!

This was an interesting read, though just a correction- Elsie kisses Clementine, not Maeve.

Hey I loved this article when it came out and I’m kinda obsessed with the sex robot trope in media. I wrote a blog post on automated sex work in TV, would be cool to hear your opinions!

https://bitchandablaster.wordpress.com/2018/07/15/enough-of-the-robot-hookers/