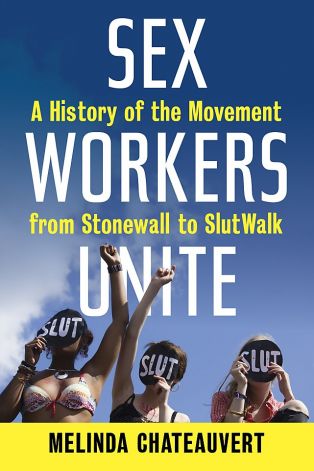

Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk, is a pretty damn good history of our movement. Still, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s critique in her review of the book—that male and genderqueer sex workers are given short shrift in Chateauvert’s work—is valid. Glancing references to Kirk Read and HOOK Online aside, the book is a bit of a hen party.

Any book that aspires to be the first history of the sex workers’ rights movement in the United States will inevitably face accusations of exclusion. But despite some unavoidable failures in representation, Mindy Chateauvert’s Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk, is a pretty damn good history of our movement. Still, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s critique in her review of the book—that male and genderqueer sex workers are given short shrift in Chateauvert’s work—is valid. Glancing references to Kirk Read and HOOK Online aside, the book is a bit of a hen party.

Then again, so is the movement it chronicles. Sex Workers Unite is a fairly accurate portrayal of our organizing, for better or worse. The index and the footnotes provided me with a comforting sense of familiarity as my eye skimmed over names well known to me, from Carol Leigh to Kate Zen. (Full disclosure: Tits and Sass posts were often cited, including one of my own.) At least, finally, in this text trans women sex workers are given the central role in our story that they’ve played in our activism. The book covers early movement trans heroines like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in depth, documenting their participation in the Stonewall riot and their founding of STAR House, a community program serving queer and trans youth in the sex trades. They were also involved in the lesser known organization GLF (Gay Liberation Front), an anti-capitalist group that “made room for prostitutes and hustlers, including transwomen, straight and lesbian prostitutes, gay-for-pay hustlers and stone butch dyke pimps,” but hilariously enough, couldn’t come to a consensus on whether it was still okay to take money for sex after the revolution. Chateauvert follows this thread of trans history throughout, never failing to highlight trans women sex workers’ contributions to such integral activist projects as Women with a Vision, HIPS, and Washington DC’s Trans Empowerment Project, as well as their more general influence in shaping sex worker culture.

When I first picked up the book and noted the subtitle, I felt a brief pang of disappointment at the fact that our movement is still so little-known that the the two iconic events that bookend Chateauvert’s summation of our chronology in her title—Stonewall and Slutwalk—actually properly belong to other movements. But as I started to read, I was delighted to realize what the author had done by integrating our narrative with that of so many other struggles for social justice, reminding the reader of sex workers’ critical participation in so many movements over the decades. From GLBT/queer rights and feminism to AIDS activism and harm reduction, Sex Workers Unite makes it clear that you can’t really talk about the history of activism in the US without talking about us. The book tackles our invisibility in these integral roles—in its chapter on Stonewall, for example, it highlights the rarely mentioned fact that drug using trans sex workers were the key participants of the riot, and strips the respectability politics from the typical portrayal of Stonewall rioter Rivera, who is often remembered as a trans activist forebear but not so often revered for supporting her activism via street sex work.

Chateauvert also blends our history seamlessly with broader American trends in both sex and labor, explaining in an early chapter, for example, how an economic downturn, an increase in the price of heroin, and changing sexual mores worked to heterogenize the street sex work market in Times Square in the late 60s and early 70s, driving a diverse pool of women in to compete for turf they had previously left to white lower middle class street workers, sparking racist backlash from Mayor Lindsay’s police task force. In a later chapter, she writes about how both deindustrialization and reactions to AIDS destroyed public sex spaces throughout the 80s and early 90s, freeing up the field for the advent of telecommunications, video, cable, the Internet, and cell phones to usher in the diversification of the indoor sex industry by the late 90s.

Sex Workers Unite offers a lot to very different audiences. This book could take its place on a syllabus for a class on sex workers’ rights as a comprehensive primer for those who know nothing about our work, introducing them to such basic key movement milestones as the 1973 founding of Margo St James’ COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), the first political organization by and for sex workers in the US, as well as the Lusty Lady’s peepshow workers’ collective bargaining agreement victory in 1996. Chateauvert’s substantive research also introduces new information to someone like myself, with ten years of experience in sex workers’ rights milieus. Despite how often I’ve read about COYOTE over the years, I had no idea that they successfully challenged a California venereal disease quarantine law for women arrested for prostitution, as well as effecting a year-long moratorium on prostitution arrests in San Francisco in 1976. The text also educated me on facets of the movement I’d known nothing about, such as the formation of ACE (AIDS Counseling and Education) by injection drug-using and sex working women prisoners at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in the early 80s. And a summation of the history of police violence against sex workers and sex workers’ resistance to it, which Sex Workers Unite provides in one of its chapters, is invaluable to any reader. The sheer depth and breadth of study evident in the book ensures its usefulness as a resource.

But Sex Workers Unite is much more than a collection of facts and figures, however comprehensive. Chateauvert displays a deft hand with subtle ideas. I was intrigued by her analysis of why liberal movements fail to include sex workers’ rights in their agendas, never having seen it conceptualized quite so simply and understandably before: liberal dogma bases sexual rights on the right to privacy, and sex work, as sex that takes place in the public sphere of the market, does not fit under that umbrella. In the chapter on AIDS, the book illustrates the tragic downfall of the scientific association of diseases with identities—as veteran activist Synn Stern lamented in her Tits and Sass interview, “It was years before we were able to get people to move from thinking about ‘risk groups’—’faggots,’ ‘junkies,’ ‘hookers,’ ‘Haitians’—to ‘risk behaviors.’” During those years, as Sex Workers Unite poignantly chronicles, women with AIDS were ignored and HIV positive sex workers were criminalized.

Throughout the work, Chateauvert promotes a more complex understanding of our movement. We need to move beyond identity politics to a more generalized human rights based approach, she urges. After all, focusing on decriminalization alone as a goal will leave non-full service sex workers out in the cold, while only talking to other sex workers leaves us with a coalition of only those who identify as such and excludes all other groups who suffer along similar axes of oppression. Broadening our focus can only make us stronger.

On Wednesday, 3/12, Mindy Chateauvert will be speaking about Sex Workers Unite at two venues in Washington, D.C.—the ACLU Washington office at noon, and Busboys and Poets at 6:30 PM. On April 5-6, she will be in Ontario at the 2nd Annual Feminist Porn Conference. Check out the other remaining dates on her book tour at the book site or on the author’s Facebook page.

love it. I was so upset that I missed Mindy’s reading at bluestockings! This was the book that always needed to be written and I must confess ecstasy that now it is, she’s a bad ass! Very well written and insightful review Caty, I can’t wait to start the book!

Hello sir,

Thank you for reply.Sex Workers Unite offers a lot to very different audiences. This book could take its place on a syllabus for a class on sex workers’ rights as a comprehensive primer for those who know nothing about our work.

Thanks……….