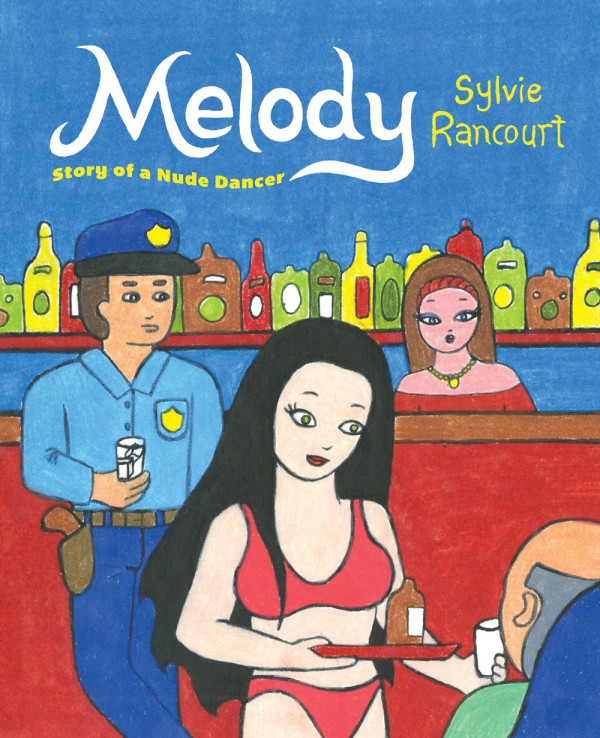

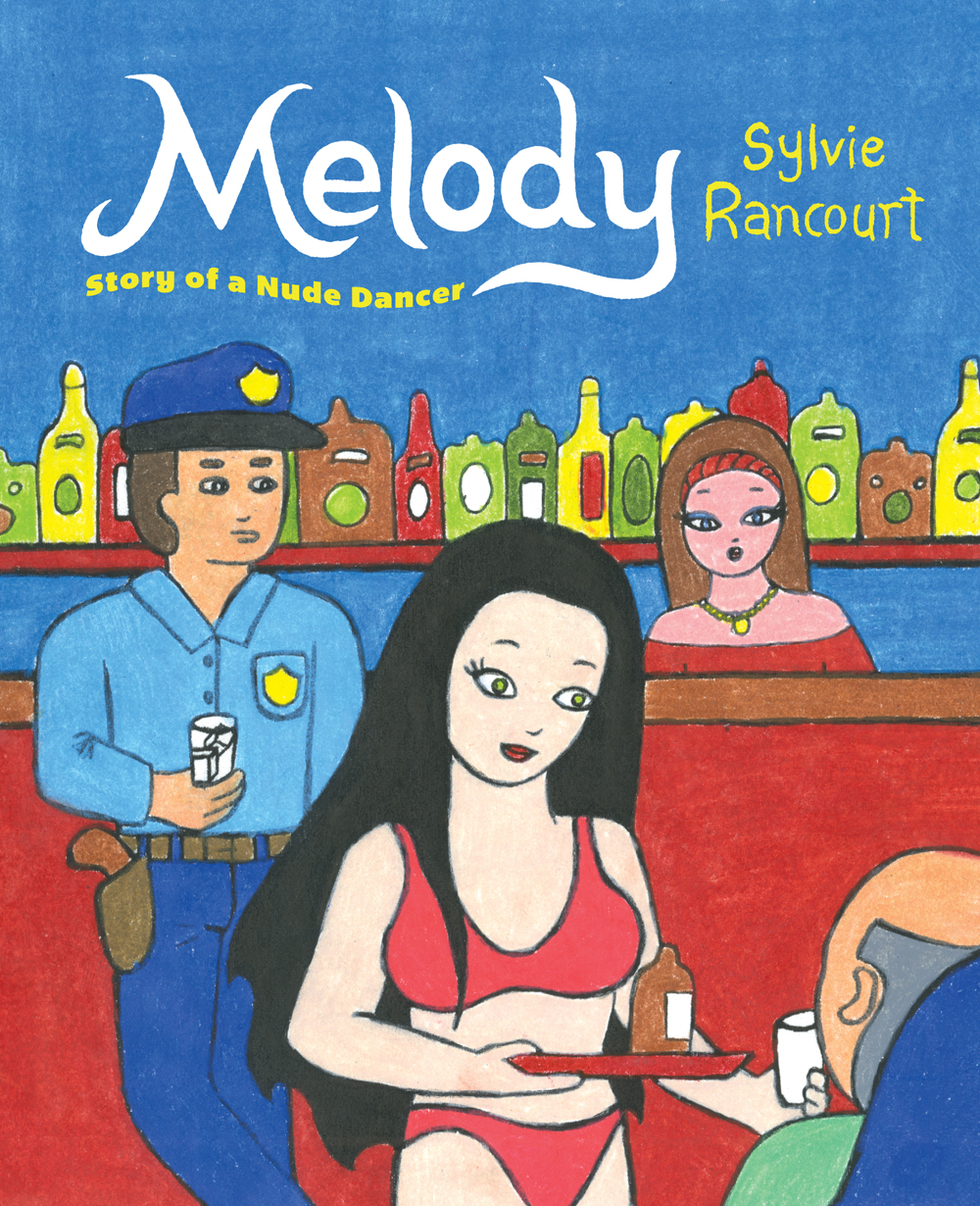

Melody: Story of a Nude Dancer is one of the first autobiographical graphic novels ever published in Canada. The author and artist, Sylvie Rancourt, was a stripper in Montreal in the 1980s. She would write, draw, print, and distribute her comics in the clubs where she danced. Badass, right?

Melody: Story of a Nude Dancer is one of the first autobiographical graphic novels ever published in Canada. The author and artist, Sylvie Rancourt, was a stripper in Montreal in the 1980s. She would write, draw, print, and distribute her comics in the clubs where she danced. Badass, right?

In spite of my recent attempts at being an illustrator, I’m very new to the graphic novel community. My first impression of Melody was surprise at the (ahem) normcore nature of her work. I expected a highly sensationalized story not unlike Pamela Anderson’s Stripperella (may Stripperella rest in peace). Melody, however, is quite the opposite: it reads like the visual diary of a girl unsure. Unsure of what? Everything.

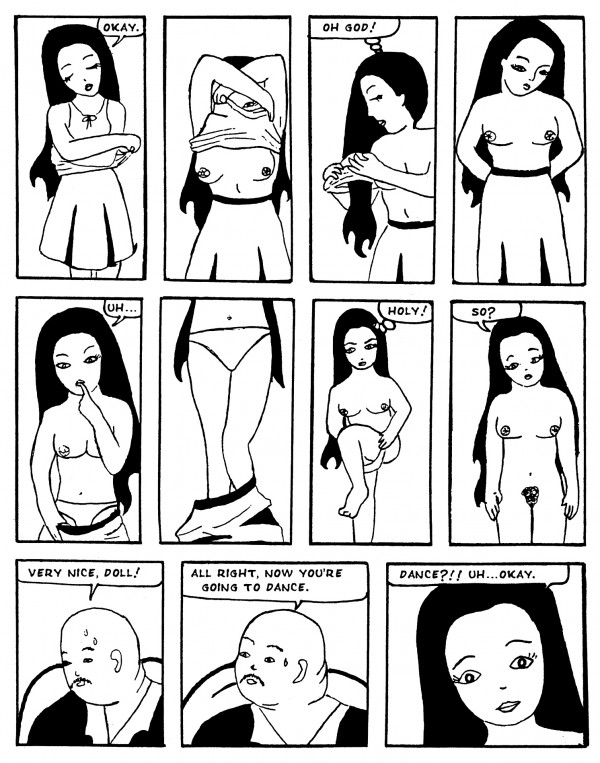

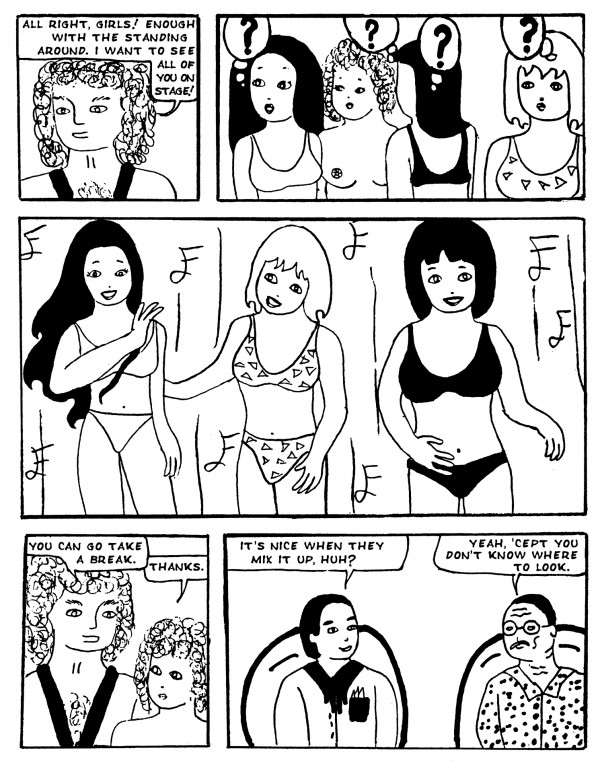

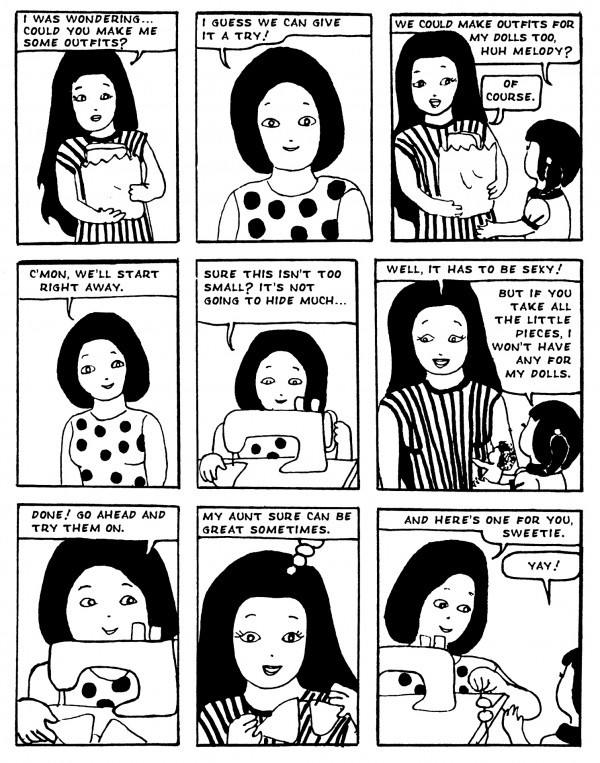

The story begins with Melody moving to Montreal with her husband, who suggests she starts dancing to support them while he looks for work. Sheepishly, Melody complies and auditions at a club, Bar 320, where her husband soon starts showing up to sell blow. With a sigh, Melody learns the ins and outs of stage shows, tipping culture, hustle, and fantasy, all the while maintaining ignorance of her husband’s criminal activity. She does, however, start to enjoy performing on stage upon incorporating comedy into her routines with a small hand puppet of a naked man. Alas, management doesn’t understand Melody’s sense of humor and demands that she continue her stages without her micropenis-wielding sidekick. The plot becomes bleaker as Melody gets fired for always being late to work and her husband starts to cut the blow with baking soda and begins also selling hot electronics to Melody’s colleagues and customers.

Rancourt’s account of all this is that Melody passively goes about her work, knowing nothing about her husband’s drug dealing and fencing. I almost wonder, was Rancourt as innocent as she claims Melody was? Or did she claim to know nothing for the sake of her job security at the time? She was, after all, passing around her comics at the clubs where she worked, so presumably she was in a good position to hear club gossip. At times, Melody reads like a testimony to Rancourt’s innocence.

I kept reading because I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the illustrations. Rancourt’s drawings are incredible. She paints these incredible aerial-perspective tableaus of a strip club in full swing. I could stare at these images for hours. A woman splays her limbs on the stage while thought clouds and speech bubbles float above clients of varying ages and ethnicities as they enjoy her performance at the tip rail. A stripper’s mother walks into the club with her boyfriend, so the young dancer hides under a table and gives a random client a blowjob to pass the time. I want a print of that image for my wall.

I kept reading because I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the illustrations. Rancourt’s drawings are incredible. She paints these incredible aerial-perspective tableaus of a strip club in full swing. I could stare at these images for hours. A woman splays her limbs on the stage while thought clouds and speech bubbles float above clients of varying ages and ethnicities as they enjoy her performance at the tip rail. A stripper’s mother walks into the club with her boyfriend, so the young dancer hides under a table and gives a random client a blowjob to pass the time. I want a print of that image for my wall.

I also couldn’t stop reading because I wanted it to get better for Melody. I wanted her to find happiness and leave her shitty husband. I wanted her to love stripping like I do.

I could go on to say that it was a different time, because it was. I didn’t dance in the 80s, but from what the veterans tell me, it’s regarded as the heyday for strippers; a time when cocaine fell from the sky and women were showered with money for merely existing. It was also a time, especially in Quebec, of sexual conservatism, high Catholicism, and second wave feminism (recall the protests at the Miss America pageant; women are not objects for your consumption). At one point in the story, Melody thinks she is home alone, and walks through her kitchen naked. She is suddenly greeted by her shocked and disgusted mother-in-law. Melody rushes back to her room to put a robe on, telling herself, “I’ve lost all my modesty since I started dancing…”

I could go on to say that it was a different time, because it was. I didn’t dance in the 80s, but from what the veterans tell me, it’s regarded as the heyday for strippers; a time when cocaine fell from the sky and women were showered with money for merely existing. It was also a time, especially in Quebec, of sexual conservatism, high Catholicism, and second wave feminism (recall the protests at the Miss America pageant; women are not objects for your consumption). At one point in the story, Melody thinks she is home alone, and walks through her kitchen naked. She is suddenly greeted by her shocked and disgusted mother-in-law. Melody rushes back to her room to put a robe on, telling herself, “I’ve lost all my modesty since I started dancing…”

It’s frustrating to read Melody, because it’s a story I’ve heard so many times in every incarnation of mainstream media’s account of the big, bad industry of adult entertainment. The sad stripper story is a device of anti-sex work rhetoric which makes me furious. Not because it’s never been true, but because the trope has been exhausted and there never seems to be any variation on the experience of a stripper beyond just being fucking sad. But Melody is different in that it is a story told by an actual stripper, who, although she didn’t particularly dig the sex work, demonstrated incredible agency and hustle in the creation, execution, and distribution of her story as a comic. Rancourt is an excellent storyteller. Her drawings are simple in a way that makes it really easy to empathize with the characters as they try to make it through the ups and downs of a shift. Her work is unpretentious, honest and real. This was her experience. And it is told honestly without a single lick of self-pity.

It’s frustrating to read Melody, because it’s a story I’ve heard so many times in every incarnation of mainstream media’s account of the big, bad industry of adult entertainment. The sad stripper story is a device of anti-sex work rhetoric which makes me furious. Not because it’s never been true, but because the trope has been exhausted and there never seems to be any variation on the experience of a stripper beyond just being fucking sad. But Melody is different in that it is a story told by an actual stripper, who, although she didn’t particularly dig the sex work, demonstrated incredible agency and hustle in the creation, execution, and distribution of her story as a comic. Rancourt is an excellent storyteller. Her drawings are simple in a way that makes it really easy to empathize with the characters as they try to make it through the ups and downs of a shift. Her work is unpretentious, honest and real. This was her experience. And it is told honestly without a single lick of self-pity.

1 comment