Like many of my LGBT peers and allies, I am grateful for the contributions made before and for the possibilities ahead. This summer, the Supreme Court acknowledged the humanity of LGBT individuals. And one of our pinnacle liberation symbols, New York City’s Stonewall Inn, the site of the 1969 Stonewall riots, was made a national landmark—all substantial markers of the rapidly increasing acceptance of LGBT individuals in mainstream America.

Over the past decades, important work to raise awareness and funds for the #gaymarriage movement has dominated the LGBT landscape. Each $1000-plate dinner and garden party brought together the well-dressed and privileged of the LGBT community to establish a strong presence against prejudiced, formidable foes. Many of these participants called on the ghost of Stonewall as an emblem of retaliation, reaction and unity. Simply by uttering the “S-word,” the President inspired LGBT people and their allies nationwide to have confidence to continue pushing for broad rights and protections. This summer our victory cry has been #lovewins.

But something is missing in all our gratitude. While it’s great that gay men and lesbians are building wedding registries, shopping at malls, and openly holding hands in places where it was previously forbidden, many of our most high profile spokespeople risk encouraging a spineless edit of history. We are so swift to lionize Stonewall and all of the early LGBT civil rights movement that the process has forced us to acquiesce to an acceptability politic which punishes many identities which represented the very heart and soul of our liberation mantras.

We must challenge our collective desire to strip a story that subverts a normative way of seeing the world. We as LGBT individuals and allies must tap our recent tragedies and triumphs to prevent our own story from disappearing into the exact same narrative most embraced by the bigots who used that norm against us.

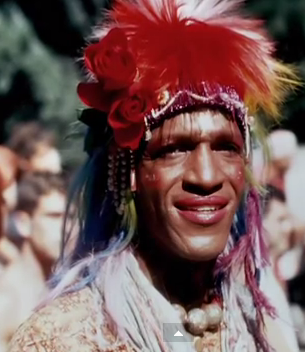

The riots at Stonewall are, in fact, the perfect example. Conversations about its history selectively ignore significant components of the rioters’ identities, often including the vital presence of trans women (Sylvia Rivera, Miss Major, Marsha P. Johnson) and gay men but excluding the fact that many of these individuals were hustlers and street workers. Look for the biography of Sylvia Rivera, one of the most well-respected trans activists and Stonewall participants, and you will find her experience of street work excised. This, despite how sex work may have formed her only available opportunity at that time to afford to engage in her activist work. She was hardly the only trans woman of color involved in the sex industry supporting the riots. And then there were the hustlers, the young men working to support themselves after escaping to the city from lives that would have ended up in false marriages, depression, or, as it did for many, suicide or deaths by gay bashing. These were the people, harassed by the police to the point of exhaustion, willing to publicly engage as LGBT people at a time of great risk, the people who actually make up our liberation narrative.

People who live on the outskirts of the norm are the ones to whom we owe the greatest debt for building the foundation on which all of our newly lauded liberations exist. If Stonewall isn’t reminder enough, then reflect on Compton’s Cafeteria Riots of 1966 where street workers enacted a similar revolt, as detailed in Melinda Chateauvert’s Sex Workers Unite. And ACT UP’s revolutionary tactics might not have been as creative, intense, or effective if it hadn’t been for the participants who were turning trade in the big city, enabling them to support its work (Iris De La Cruz, Richard Berkowitz, David Wojnarowicz, as well as many others whose legacies are still too obstructed by stigma to disclose freely)—since many of the closeted corporate kids kicked back in their hedge funds during the AIDS crisis and thought they could continue to party in private.

The entire movement’s history is still fresh, as both raw traumas and unexpected victories. The inclusion of difficult non-traditional narratives like those of sex workers is critical to prevent their permanent invisibility, which is why I appreciated Diane Anderson-Mishall’s recent Advocate Magazine piece acknowledging the sex worker movement’s significant correlation to the LGBT movement. While I am grateful for the good intentions of such acknowledgement, I fear that the default call to action is still to play sex workers as sympathetic characters rather than key players who should command respect.

The role of individuals who are either compelled or have chosen the sex industry must be included in LGBT rights conversations as we look to translate the social capital accrued over the last 40 years into tangible cultural changes. To exclude us does enormous disservice to our predecessors, who proudly understood that sex in the margins, sex as a form of agency and survival, sex as intimacy, and sex as an act of power are fundamental to LGBT identity. We encourage this by demanding respect for those who choose to be cis and trans, male, female, and genderqueer workers in the adult industry. It’s also important that we advocate for the support of programs which give space for sex industry laborers to speak and access legal, medical, and emotional health resources. Think of HOOK, SWOP, and the Sex Workers Project. Lastly, we can contribute to a national dialogue that raises attention to the intersectional factors which compel individuals towards the adult industry, like ongoing homophobia in rural areas, immigration, income inequality, misogyny, and transphobia.

#lovewins only when we don’t diminish the wonderfully diverse queerness of our community as well as make invisible the true identities of the men, women, and genderqueer liberators that got us here.

There is also John Rechy, author “City of Night” and “The Sexual Outlaw” – who was a street hustler and activist- and then professor of English at UCLA. An amazing man and a friend!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rechy

Definitely essential reading!

This is why im very proud to march as a genderqueer sex worker

Australia is a society tolerant in comparison to others.The police in both Germany and Australia have always been good to me regarding sex work. You can tell People you are gay or bisexual but not that you are a sex worker unless you are leaving town.

Nice article. Hmm, it’s great acknowledging that sex workers need to have resources in order to maintain his or her health. But I’m not completely sold on that as a form of activism. The article itself says that sex is a form of “agency and survival” so I would venture to think that it should be more of a last resort rather than a lifetime career choice. Of course, this applies to the LGBT that have the choice to begin with. So if this article speaks about the brave queer folk who happen to be sex workers, great. Just not sure if we should celebrate if it’s the other way around.

When the marginalization of any group who has no other choice to survive but sex work. The person then must do what is needed to survive. Add to this the dangers and laws that make it even worse for sex workers you end up with a mix that your only outlet is to raise your voice to be heard, No wonder at places like Coopers Donuts, Comptons Cafeteria, and Stonewall Inn to name a few that Organizations like Personal Rights in Defense and Education, P.R.I.D.E., Gay Liberation Front and Act Up developed their tactics to protest for LGBTQ rights.

Thank you for some much needed perspective on our shared history often erased and the need to push back against repression in all its forms. I also want to be sure that we do not lose sight of the reality of the human need to celebrate sex. Sex work is not only a lifeline for many workers to survive but also it provides a valuable service to clients to be themselves, to experience bodily expression and caring.