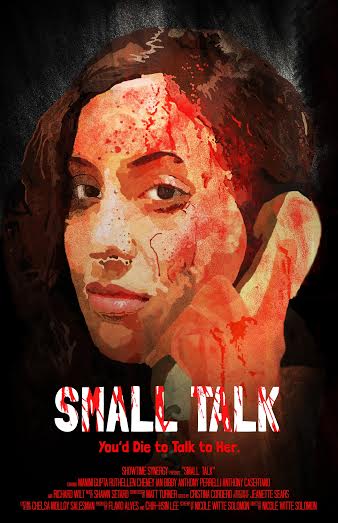

Nicole Witte Solomon and I have kept up with each other online for a while, dating back to the era when she was a young phone sex operator/film student, just beginning to pitch her clever writing on topics ranging from vegan cooking to feminism in pop culture to a variety of venues. As the years have gone by, she’s fulfilled many of her dreams, from directing a video for her favorite Jewish post-riot grrl band The Shondes to co-founding writers’ site The Stoned Crow Press. Having followed the making of her phone sex horror movie short Small Talk since its inception, it’s exciting to get a chance to interview Solomon about it as it finally makes the festival rounds.

What attracted you to horror as a genre? What sort of opportunities do you think horror provides for feminist artists?

I’m attracted to horror as a viewer because it has the potential to make me feel a wide range of intense emotions within a controlled and hopefully safe environment. A great horror director is much like a great domme; of course I gravitate towards the genre as both a viewer and filmmaker.

The whole reason Small Talk happened is I was writing a phone sex memoir and got the image in my head of a PSO taking a phone sex call while dismembering a corpse. It felt a lot more compelling than a long, tedious recounting of autobiographical detail. Horror allows us to break into the supernatural where needed and requires no happy endings.

It was enormously therapeutic for me to make this film. I had some unresolved feelings and then I exploded a couple [of] people in a movie and now I feel fucking great. I am a huge proponent of filmmaking as a form of narrative therapy and encourage any and all sex workers who have unresolved feelings to make art about it, if for no other reason than my own selfish one of I really can go the rest of my fucking life without reading, viewing or otherwise consuming a sex worker narrative by a non-sex worker, and god knows everyone else is apparently starved for them [narratives by and about sex workers] and—

The horror community has been by far the most welcoming of the film. I submitted it to a ton of “women’s” film festivals and not a single one has wanted to touch it. One festival that rejected me offered to send a summary of jury comments for free and the comments were basically like “It was well shot and acted and all but it was about a phone sex operator and it was so disturbing and suddenly people were exploding and I don’t understand why and our audience will be so disturbed and upset.” That was the consensus of why my film was a bad choice for their festival.

I was impressed with how Manini Gupta, as the phone sex operator protagonist, Al, was so versatile with the affect of her voice as she worked the line. And I empathized with her so much as she rolled her eyes through most of those calls. What were you looking for in the actress that would play the PSO? What was most important for you to say about being a phone sex operator in your movie?

It was not easy finding someone who could do all the things you mentioned, and the most important thing to me was that the actress I cast be believable—to me. That was the litmus test. I needed someone who could 1. Convincingly play all those things on the PSO fantasy end—sound like a believable, good PSO while also 2. Play the Al character’s own, usually conflicting reaction to what’s going on. Manini was totally on the right track from the first audition, whereas most people I saw couldn’t really do either, let alone both at the same time.

In terms of what I wanted to say about being a PSO—I guess I wanted to portray it as a challenging job involving a particular skill set. I wanted to show some of the less savory aspects of the job without demeaning it in any way. I wanted to open up to the world about the specific aspects that can be difficult and sometimes emotionally damaging in a way that contextualized it within a broader service industry—looking at race and gender dynamics within capitalism in general, not just the sex industry specifically or the phone sex industry in particular. I meant this film as a kind of valentine to other PSOs, honestly. Our labor and skills are so commonly undervalued and misunderstood, and what we do is so tricky, if we do it well.

I felt a frisson of real fear when Al’s landlord grabbed the phone as she was talking to a client and gave him her address. I was also just flummoxed when a bunch of clients ended up giving Al their info, as well. How often did those boundaries get blurred when you were working as a phone sex operator?

I’ve anecdotally noticed that sex workers and people who have done sex work in the part react strongly to that part. Which makes sense—I included it because I was making a horror movie about a kind of sex work and tapping into some of my own deepest fears about it.

That scene was based on something that actually happened to me, when my landlord knocked on my bedroom door while I was in the middle of a call. Luckily, it was a domme call, so I just put the guy on hold, which worked perfectly as another degrading test of his loyalty to me and [a] demonstration of his general worthlessness. The sub stayed quiet, and I made my landlord go away, and it was fine. But I was still thrown by it. Having clear, firm boundaries is so crucial. That landlord really liked me, but he was also really bad with boundaries, and I put up with it because I had a large apartment in a good location for below market value, and he didn’t raise my rent for five years. That moment raised the specter of things going worse than they actually did.

As for the callers: they would try to give me their personal info fairly frequently. I would be reduced to talking over them as they gave it to me, like ”lal la la I can’t hear you!” as I could get in trouble if I was being monitored by the service I worked for, and I didn’t want it [the information], anyway.

But yeah, boundary crossing of this sort is a huge theme in the film. Thankfully, no one ever found out where I lived.

Al struggles to make sure her callers keep to the rules of her phone sex company and don’t discuss drugs, pedophilia, or rape. Did you ever get in trouble because callers crossed these lines?

This one regular had a very specific wrestling fetish involving leg injuries, so I would graphically detail the terrible, painful leg injuries I sustained in my many wrestling matches. I was told I had to keep the injury descriptions within certain lines that, from an ethical (if not legal) standard were pretty arbitrary. I wasn’t supposed to discuss “mutilation” and I didn’t think I was—I was discussing bruising, swelling, sprains and, in the most extreme case, bone breakage. I kind of thought as long as there was no blood (which was explicitly forbidden), I was okay. But for whatever reasons the person monitoring [the call] got spooked and told me I had to tone it down.

There were so many calls that, to my mind, were much more disturbing and damaging (at least to me) that we were not allowed to decline because they were within company parameters. So we had to talk about rape, but were forbidden from discussing “violent rape”—we can all try to wrap our brains around that one. Meanwhile, I had a regular who always wanted to go through a fantasy about killing his wife, but that was fine because we spoke in code (“end” instead of “kill” her and the like.)

Instead of having the sex worker be the shrieking victim of the horror movie, you flipped the script and had her be the source of the terrifying phenomenon. What were you saying about the monster and the monstrous in all of us with that decision?

Well, you just hit on the whole genesis of this movie, which was me reckoning with aspects of myself that came out during my near-decade as a PSO, specifically a non-consensually sadistic streak.

I would at times turn into a kind of bully on the phone—you can get away with saying a whole lot of shit [as a PSO] if you do it in a sexy voice, especially while playing dumb. I would actively try to undermine these callers’ sense of self. I would intentionally make their erections go down while pretending to try to get them off—sometimes by feigning shock that they hadn’t had certain experiences and thus didn’t have certain skills—not in an “I’m a super slut who has done everything and one in the world” fantasy way, but in a “you’re a loser virgin” way. If I wanted to get a guy off the phone I’d talk about how I wanted to have a three way with two men, or how I always fucked every guy with a strap on, guessing correctly that I’d likely scare the caller into hanging up. That’s still funny to me, to be honest. I can’t help but connect that satisfaction on my end to the nonconsensual sadistic satisfaction some of my callers took in intentionally crossing my boundaries and making me genuinely uncomfortable. The film is largely about me wrestling with a monster inside myself. And I think we all have similar monsters lying in wait.

Horror is a great way to address a lot of sex work stuff because it’s so much about exploring the deep, scary and upsetting parts of ourselves and our world that we don’t want to look at. Scaring someone, touching them in that deeply personal way, is pretty similar to intentionally turning them on. I’ve said that I learned how to direct actors by doing phone sex and people think it’s a funny quip, but I’m dead serious. Phone sex is so much about going to deep, oft-unexplored places of the caller’s psyche, following what turns them on, and often what is there is pretty ugly. [Well, actually,] often what’s there is totally benign, but the caller has been taught it’s ugly. But sometimes it’s [a case like] the guy I mentioned who would jack off while imagining his wife being murdered. One time he broke down crying at the end of the call and wanted me to tell him I loved him. Some of my coworkers would draw the line at saying that, but I was more okay with that part than the rest of the call. Which I did anyway for a bunch of complicated reasons, including but not limited to: I needed the money? How am I supposed to deal with those kinds of dynamics in film without making a horror film? To me it just feel[s] completely natural. I could make a really fucking depressing drama that no one, including me, would want to watch, I guess. I’d rather do this.

All of the callers in Small Talk are based on real people I used to talk to. The pedophile was based on a real guy who had an underage fantasy (which we theoretically weren’t supposed to do, but did all the time in coded terms) and then at a certain point I heard a kid’s voice in the room over the phone. He hung up and I freaked the fuck out. I had zero access to any information about him. I didn’t approach management because I knew what they’d say, which was so what, some guy got interrupted by his kid, he must be so embarrassed, nothing we can do. So I did nothing but stew in this awful, impotent, disgusting feeling. Yeah, I obviously hope to god that that guy just had an (extremely common) fantasy and not only wasn’t abusing that kid, but had absolutely no desire to do so, but I’m still a little haunted by it today. Without spoilers, playing through it in the supernatural horror context of Small Talk was a no-brainer.

Same with the guys who I suspected of taping me, the creepy hobbyists, the aggro and abusive cokeheads, the enormous misogynists who get off on hurting you—not BDSM “hurting you”, genuinely violating you in one way or another. You tell someone who hasn’t had a job requiring them to deal with that kind of shit about it, and they’re horrified. I’m horrified, albeit perhaps more jaded about it. Horror is the obvious way, to me, to package this kind of content so that viewers can take it in and wrestle with it in a safe and hopefully both educational and enjoyable way, without my having to sanitize it. And gore is a great way to make psychic wounds blatantly visible.

I loved how, although a bunch of Al’s victims are bad callers—pedophilic callers or callers who threaten her with rape, who become victims of her burnout as she literally makes them explode with her brain—you took time in your short film to show a good caller with a smoking fetish which allows Al to relax and get stoned at work. Do you think most viewers will get the point that the villains of the piece are villains because they’re entitled white men, not because they consume a sex worker’s services?

I tried to give non-sex worker viewers some guideposts to get there, because that is exactly my point.

It’s interesting and not that surprising that you specifically mentioned the two scenes that non-sex workers most urged me to cut (23 minutes is long for a short, and the length has cut me out of a lot of screenings and festivals) and I wouldn’t. I actually screened a version without the smoking fetish scene, because I was trying to be open and take feedback and I thought “Well, it’s a HORROR movie, and a short one, obviously I’m going to focus on HORRIFYING calls, which aren’t the bulk of them, and if people take from this that all phone sex calls are horrible and traumatizing that’s their problem.” I obviously wasn’t sold on my own justification.

The villain that you portray at the beginning of the movie is a fundraiser for an anti-sex work/”anti-trafficking” campaign, brandishing faux stats like “99 percent of prostitutes start working before they’re 13!” He tries to get Al to sign something for her office which as a temp, she has no authority to do. The way you depict him, he’s strong arming her like a drug dealer in a 1980s PSA hard selling to a kid. What was the inspiration for this character?

That character came about just from brainstorming with my partner about what non-phone sex temp job Al could get and what asshole we could have interact with her there. I chose a recording studio because I knew someone who had a pretty one and hoped he’d let me shoot there, and my partner suggested that someone could come lean on her for some charity auction goods, which I loved because: why not drag in an ugly side of the nonprofit industrial complex? To then make the charity be some bullshit, top-heavy, nonsense-spewing, celebrity-infested anti-sex trafficking initiative was just a no-brainer.

I hope to god that my putting that in there puts the idea of a slimy, lying anti-trafficking professional in the heads of some people who didn’t previously have any visceral problem with such things. I used to have an annotated version of the script up online that linked to breakdowns of the actual phony stats every anti-trafficking org regurgitates, as well as critiques of anti-trafficking orgs that are actually just anti-sex work, rarely help rather than harm sex trafficking victims, and don’t give a shit about the majority of actual trafficking victims, who are forced into other forms of labor which are less titillating and funding-provoking, The horrors of the anti-trafficking industrial complex are largely unknown to people outside of sex worker activism and the communities directly affected by their policies, so I absolutely wanted a platform on which to raise them to a broader (or at least different) audience. I also just really, really wanted to get a Nicholas Kristof dig in on a fancy RED camera.

Solomon’s short film about Joan of Arc for the Bring Us Your Women anthology will premiere at the Oberon Theater in Cambridge, MA on Feb 27 (Tickets here). More Small Talk screenings will be announced soon: watch the website and follow the film on Facebook, Twitter (@Smalltalkmovie) and Tumblr to see when it’ll be playing near you.

1 comment