Alana Massey’s new collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers, is a fucking love song to sex workers. Yet, Massey’s own erotic labor—both licit and ambiguous—is not the focus of the work. Massey interrogates “our collective ownership” of considerable female figures like Britney Spears, Scarlett Johansson, Amber Rose, Lil’ Kim, and others in 15 brief essays. Throughout the book, her own sex work plays a more subtle role in her analytic critique of what, exactly, it means to be owned. But being metaphorically owned—by the public, by stringent gender roles, by a lack of resources, etc.—sits at the intersection of class and race, and Massey isn’t afraid to have those complicated conversations.

Alana Massey’s new collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers, is a fucking love song to sex workers. Yet, Massey’s own erotic labor—both licit and ambiguous—is not the focus of the work. Massey interrogates “our collective ownership” of considerable female figures like Britney Spears, Scarlett Johansson, Amber Rose, Lil’ Kim, and others in 15 brief essays. Throughout the book, her own sex work plays a more subtle role in her analytic critique of what, exactly, it means to be owned. But being metaphorically owned—by the public, by stringent gender roles, by a lack of resources, etc.—sits at the intersection of class and race, and Massey isn’t afraid to have those complicated conversations.

In her examination of 25 female celebrities, from Anna Nicole Smith to Princess Diana, Massey looks at how the public consumption of famous women influences the construction of gender and sexuality more generally. “Britney’s body is everybody’s,” Massey says, before expanding on the public’s “particularly pathological focus on her [Britney’s] claim to be a virgin.” This pathological focus on virginity is of course in stark contrast to Massey’s own erotic labor, where her own virginity is never in question. While Massey does not belabor the point, All the Lives I Want is centrally about the organizing force of the Madonna/Whore complex in the lives of all women, using celebrity culture as its lens.

Notably, Massey writes of listening to Beyonce while dancing as a stripper. She reflects on the “curmudgeonly old-guard feminists” who lampoon Beyonce’s “Run the World (Girls)” because of claims that “women do not, in fact, run the world.” Standing in seven-inch heels and grinding on a crotch, Massey concludes that “girls run the world in the sense that they perform the invisible and unappreciated labor that keep the world on its axis. That is different from doing what everyone wants to do, which is rule the world.” She is neither overly optimistic about her role as a sex worker under patriarchy nor does she apologize for it. Likewise, she is not seduced by the pretty things of femininity but rather describes them as a necessary force of destruction.

Curiously, however, “sex work” is not Massey’s preferred term when delving into her personal narrative, despite her forthright descriptions of blowing sugar daddies and fucking strip club regulars. Even the dust jacket of All the Lives I Want references the juxtaposition of Massey’s sex work with her opulent cultural critique as, merely, “an exploration into the female economy.” While perhaps this is calculated, linguistic sorcery from the wands of editors, a means by which Massey’s work can be distinguished from the over-saturated genre of white, cis sex worker memoir, I could not help but notice the its omission. Similarly, at times Massey’s class status feels distracting. While I admire her truthfulness, I am admittedly unfamiliar with, for example, “low grade cocaine,” which she references in an essay about attending NYU with Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen. As a once seasoned coke user myself, I’ve never heard the expression. My understanding of the drug has always been that it is either “good shit” or “bleach.” To place the drug in a hierarchy of grades is completely foreign to me. This foreignness is just one example of the necessity for critical reflection on lateral whorephobia, a conversation that is thankfully happening more frequently. It is important to acknowledge these socioeconomic differences, even between sex workers. Massey has the choice to exclude “sex worker” from her self-identification, and that is a privilege that is not extended to all of us.

However, I do not wish to discount the ways that Massey clearly struggles. The title—a sorrowful plea from the notoriously melancholy Sylvia Plath—appears on the cover emblazoned in gold glitter. To the untrained, civilian eye, the use of Plath mourning, “I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want […]” seems like a nod to the alleged prettiness of female suffering. But only a sex worker knows that glitter can be as dark as the agony that precedes its application. In reference to a $900 antipsychotic prescription, for example, Massey states, “I knew the shortest distance between me and $900 was the length of a hot-pink nylon-and-spandex minidress covering a quarter of my body.” Indeed, these pretty artifacts of femininity—glitter the reigning objet d’art—are every bit as severe as the crushing insistence, whispered through the winds of patriarchy, that women stick their heads in an oven. And in this book, Massey demands a rearticulation of female suffering through the sparkling lens of sex work and celebrity, two cohorts of women whose lives and bodies are ruthlessly consumed by an unforgiving public.

Alana Massey’s new collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers, is a fucking love song to sex workers. Yet, Massey’s own erotic labor—both licit and ambiguous—is not the focus of the work. Massey interrogates “our collective ownership” of considerable female figures like Britney Spears, Scarlett Johansson, Amber Rose, Lil’ Kim, and others in 15 brief essays. Throughout the book, her own sex work plays a more subtle role in her analytic critique of what, exactly, it means to be owned. But being metaphorically owned—by the public, by stringent gender roles, by a lack of resources, etc.—sits at the intersection of class and race, and Massey isn’t afraid to have those complicated conversations.

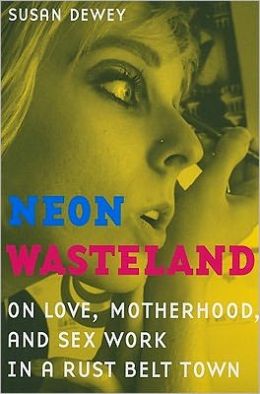

Alana Massey’s new collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers, is a fucking love song to sex workers. Yet, Massey’s own erotic labor—both licit and ambiguous—is not the focus of the work. Massey interrogates “our collective ownership” of considerable female figures like Britney Spears, Scarlett Johansson, Amber Rose, Lil’ Kim, and others in 15 brief essays. Throughout the book, her own sex work plays a more subtle role in her analytic critique of what, exactly, it means to be owned. But being metaphorically owned—by the public, by stringent gender roles, by a lack of resources, etc.—sits at the intersection of class and race, and Massey isn’t afraid to have those complicated conversations. Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers.

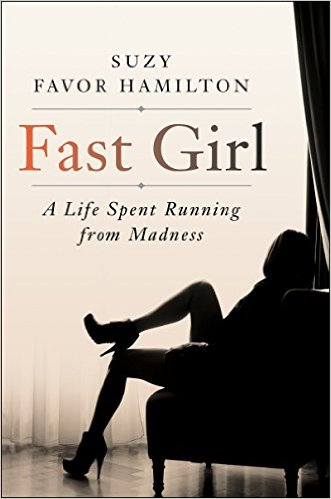

Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers. Suzy Favor Hamilton’s autobiography, Fast Girl: A Life Spent Running From Madness, catalogs the Olympic runner’s experience with mental illness, her career shift from professional mid-distance running to high-end escorting, and her eventual outing and diagnosis as bipolar. Following the birth of her daughter and her retirement from running, Favor Hamilton found her career path fraught and unsatisfactory, its travails amplified by her growing problems with postpartum depression and bipolar. Eventually, the media outed her as a sex worker, exacerbating her struggles.

Suzy Favor Hamilton’s autobiography, Fast Girl: A Life Spent Running From Madness, catalogs the Olympic runner’s experience with mental illness, her career shift from professional mid-distance running to high-end escorting, and her eventual outing and diagnosis as bipolar. Following the birth of her daughter and her retirement from running, Favor Hamilton found her career path fraught and unsatisfactory, its travails amplified by her growing problems with postpartum depression and bipolar. Eventually, the media outed her as a sex worker, exacerbating her struggles.