It’s been 24 years since Elizabeth Berkley licked the pole in Showgirls and I’m still mad about it, so I understand the mixture of anticipation and dread with which strippers await Hustlers. What stupid misconceptions will it leave the audience with? How many years will it be the general public’s touchstone for what we do?… Continue reading Hustlers (2019)

Category: Reviews

Bonding (2019)

“It’s your life story!” a friend texted me on April 24th along with a screenshot of Netflix’s new show Bonding. It was one of five or six texts I received that day from friends and clients making sure I’d heard about this new program that follows a dominatrix/grad student in and out of the dungeon.… Continue reading Bonding (2019)

Altered Carbon (2018)

Content warning: this review contains graphic discussion of the rape, torture, assault, and murder of sex workers; as well as spoilers after the jump. For the uninitiated, Altered Carbon is the story of Takeshi Kovacs (Joel Kinnaman), a biracial man “resleeved” into the body of a beautiful, dirty blonde-haired, and incredibly hard-bodied white man in… Continue reading Altered Carbon (2018)

All The Lives I Want (2017)

Alana Massey’s new collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers, is a fucking love song to sex workers. Yet, Massey’s own erotic labor—both licit and ambiguous—is not the focus of the work. Massey interrogates “our collective ownership” of considerable female figures like Britney Spears, Scarlett… Continue reading All The Lives I Want (2017)

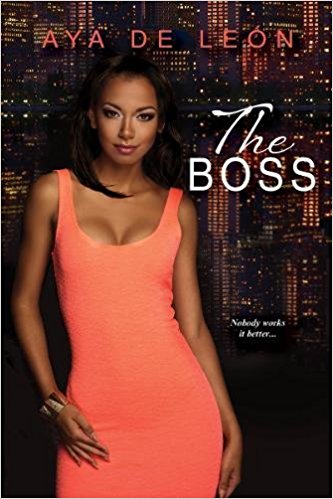

The Boss (2017)

Aya de Leon’s new novel, The Boss, tackles the real issues of sex work in a criminalized society without ever coming across as preachy. De Leon uses the experiences of sex workers and her own life to bring the reader into a diverse, vibrant, and intersectional world. As an isolated black femme sex worker living… Continue reading The Boss (2017)