In 2008, high school student Alissa Afonina, her mother Alla Afonina, and her brother were in a disastrous car accident on the Trans-Canada highway, the result of her mother’s boyfriend Peter Jansson’s reckless driving running the car off the road and overturning it. Both Alissa and her mother suffered brain injuries. Alla, a Russian immigrant… Continue reading Having The Option: Alissa Afonina/Sasha Mizaree On Her Case And Being A Disabled Sex Worker

Category: Interviews

Nothing Scarier Than A Black Trans Woman With A Degree: An Interview With Monica Jones

In May 2013, sex worker and trans rights activist and Arizona State University social work student Monica Jones was charged with “manifestation of prostitution” in Phoenix after accepting a ride from an undercover cop. Her arrest ignited a firestorm of protest against Project ROSE, a prostitution arrest diversion program run by the ASU School of Social Work and the Phoenix… Continue reading Nothing Scarier Than A Black Trans Woman With A Degree: An Interview With Monica Jones

Gore and Psychic Wounds: Nicole Witte Solomon on Horror, Phone Sex, and Film

Nicole Witte Solomon and I have kept up with each other online for a while, dating back to the era when she was a young phone sex operator/film student, just beginning to pitch her clever writing on topics ranging from vegan cooking to feminism in pop culture to a variety of venues. As the years… Continue reading Gore and Psychic Wounds: Nicole Witte Solomon on Horror, Phone Sex, and Film

The Truth Will Come Out: An Interview With Jill Brenneman and Amanda Brooks

Interview co-authored by Josephine and Caty Content warning—the following contains descriptions of extreme injuries and rape suffered by two sex workers due to a campaign of violence by an abusive client, as well as an account of child abuse. Jill Brenneman and Amanda Brooks are veterans and heroines of the sex workers’ rights movement. As… Continue reading The Truth Will Come Out: An Interview With Jill Brenneman and Amanda Brooks

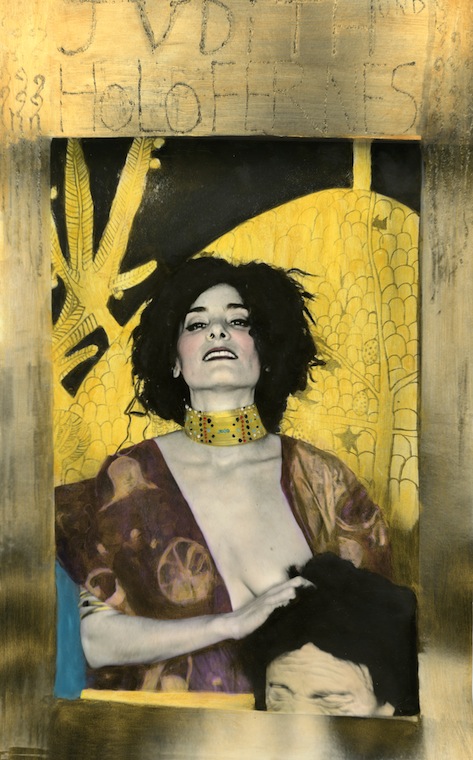

Moving Through Archetypes: Juniper Fleming and Reclamation and (Dis)Atonement

I interviewed sex worker artist Juniper Fleming on her collaborative photo series with other sex workers, Reclamation and (Dis)Atonement. Your project consists of remaking iconic Western art works, creating photographic reproductions in which you replace the main figures in the paintings with sex workers. What does depicting sex workers in these roles achieve? As sex… Continue reading Moving Through Archetypes: Juniper Fleming and Reclamation and (Dis)Atonement