An unholy mix of gentrification and trafficking hysteria created the perfect political climate to allow law enforcement to shutter several New Orleans strip clubs, leaving scores of dancers unemployed. The Bourbon Alliance of Responsible Entertainers rapidly sprung into action; they disrupted the mayor’s press conference and organized the Unemployment March the following night, which drew… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: BARE on the Mass Closure of Strip Clubs in New Orleans

Category: Interviews

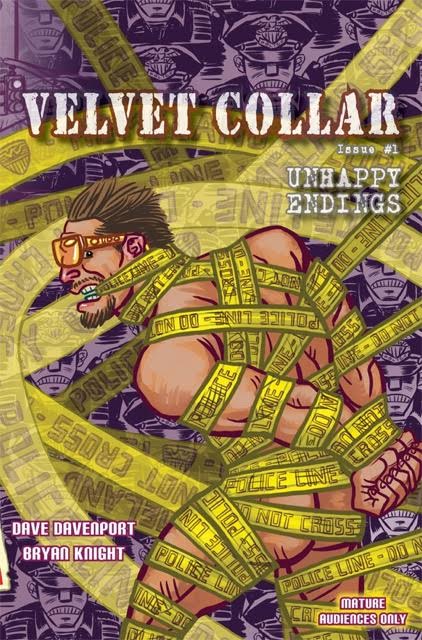

Velvet Collar, The Rentboy Raid Inspired Comic Book

Velvet Collar is a comic book series written and produced by worker Bryan Knight and drawn by queer comic artist Dave Davenport. It depicts the lives of five male sex workers. In the course of the series’ narrative, an escort listing service is shut down by the feds—a thinly-veiled representation of the Rentboy raid and… Continue reading Velvet Collar, The Rentboy Raid Inspired Comic Book

Activist Spotlight Interview: PJ Starr On Marcia Powell And Prison Abolition

Editor’s note, 8/31/2017: In light of Trump’s pardon of former sheriff Joe Arpaio for his contempt of court conviction re: the order to cease his reign of terror against immigrants in Arizona’s Maricopa County, we’re posting an updated edition of my September 2014 interview with PJ Starr. I interviewed Starr on her documentary about Marcia Powell,… Continue reading Activist Spotlight Interview: PJ Starr On Marcia Powell And Prison Abolition

Activist Spotlight: Alex Andrews on SWOP Behind Bars And Service Work

Alex Andrews is the 53-year old lead organizer of both SWOP-Orlando and SWOP Behind Bars and the new North American representative to the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). For almost a decade and a half in her younger years, she did various forms of sex work—beginning with stripping to supplement her hair dressing… Continue reading Activist Spotlight: Alex Andrews on SWOP Behind Bars And Service Work

The Joke Has To Be Funny: An Interview With Vee Chattie On Their New Podcast, The Comedy Whore

One of the best people I have met through sex worker groups is undoubtedly Vee Chattie. We met in person a couple of years ago in the back seat of a car on the way to a hearing at the Capitol. Vee develops hard-hitting performance art and organizes activist events, but the bulk of their… Continue reading The Joke Has To Be Funny: An Interview With Vee Chattie On Their New Podcast, The Comedy Whore