Red: In journalist Anne Elizabeth Moore’s new book Threadbare: Clothes, Sex, And Trafficking, in which years of her reporting are illustrated by comic artists Delia Jean, Melissa Mendes, Ellen Lindner, Simon Haussle, and Leela Corman, among others, she takes us around the world, untangling the many levels of exploitation and corruption inherent in the garment industry.

Red: In journalist Anne Elizabeth Moore’s new book Threadbare: Clothes, Sex, And Trafficking, in which years of her reporting are illustrated by comic artists Delia Jean, Melissa Mendes, Ellen Lindner, Simon Haussle, and Leela Corman, among others, she takes us around the world, untangling the many levels of exploitation and corruption inherent in the garment industry.

Moore takes us way beyond the factories themselves, to shadowy zones I never heard of before reading the book. The garment industry makes use of “Free Trade Zones,” spots on U.S. soil that are exempt from all U.S. rules and regulations, where abuses run rampant.

The author connects all the threads of industrial and imperialist abuses, and presents a seamless and ugly portrait of an imperialism that never died, only changing to better fit the times—an imperialism which is still at the heart of so many exploitations and abuses worldwide. With rope from the garment industry itself, she creates a noose to hang it with. Now we gotta get more people to read the book and spread the word.

Moore interviews retail workers at H&M, a fashion model, former workers and business owners in Austria’s shrinking garment industry, and, most pertinently to us, anti-trafficking NGOs who “rescue” sex workers into the garment industry for a fraction of a living wage. All of it is painfully fascinating, the kind of horrified interest that an especially bad injury might generate, as you read on and realize how deeply all of these facets are intertwined and interdependent.

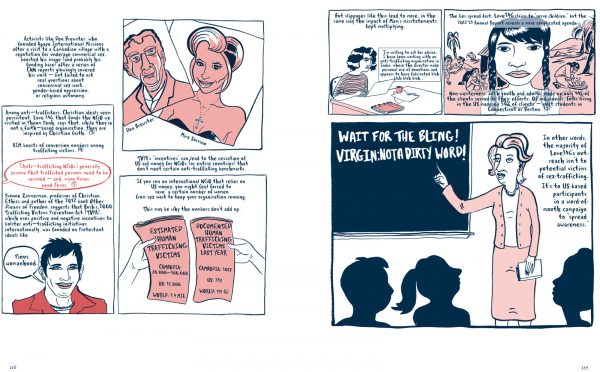

The garment industry isn’t just implicated in internationally substandard wages for women: it’s one of the root causes of them. The garment industry isn’t just loosely connected to imperialist anti-trafficking NGOs that force women into garment factories: Nike, for example, funds the anti-trafficking org Half the Sky, which is run by Nick Kristof, who not only writes openly in the New York Times about his support for and belief in the necessity of sweatshop labor—he funnels the women rescued by Half the Sky right into garment industry sweatshops which profit the very industries on the board of or funding Half the Sky! And it isn’t Just Half the Sky. Shared Hope International, the local anti-trafficking thorn in my side, has a board member who is also the international HR manager for Columbia Sportswear.

I knew before reading Threadbare that the garment industry profited off the anti-trafficking movement’s “rescue” of sex workers, but I didn’t understand just how inextricably the two were linked. I didn’t understand that it wasn’t just convenient placement and timing—it’s a deliberate, planned strategy to keep wages down and to keep women workers across the world easily exploitable.

Caty: I’m not a huge comics reader, though I’ve definitely gone through some of the classics throughout my reading life, such as Sandman and Watchmen, and on the more literary side I’ve read Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and the like. But as graphic novels get more of a foothold in sex work lit with titles like Rent Girl, The Lengths, and Melody: Story of A Nude Dancer, plus popular sex worker comic artists like Jacq The Stripper and even Tumblr darling brothelgirl, I’ve certainly been reading more comics lately. And there’s begun to be more comics coverage of leftist non-fiction, too—Harvey Pekar’s graphic history of Students for a Democratic Society particularly impressed me. So, now, finally, we have the convergence of these trends with non-fiction sex worker and labor rights comics title Threadbare.

I’m not entirely sure the comics format really works here. The fonts can be punishingly tiny, and there’s just SO much exposition. I got stalled on the book myself for months somewhere in the middle of the section on Austria’s fashion history and only ended up finishing it to write this review. On the other hand, the illustrations are gorgeous, and I’m not sure a short prose book would’ve allowed the dense material to be any more accessible.

Red: I came to comics really late; I’ve always had trouble focusing on pages where multiple things are happening. For me, images accompanying a text don’t make it easier to read, it’s too much! I love comics now, after being won over by Matt Fraction‘s Hawkeye, but reading comics and graphic novels is still a lot of work for me if I’m not using the ComiXology app. Threadbare is definitely worth the work, and many of the artists streamlined their panels in a very clear and accessible way.

I came to this book as someone who already knew a lot about exploitation in the garment industry and exploitation in the culture and running of anti-trafficking NGOs, knowledge I got through constant sifting through a sex work Google alert. People ask me for receipts all the time and I am so profoundly grateful to now have a thoroughly sourced and cited book to hand over to clinch my arguments and temporarily silence the twats.

Caty: I agree that this book should become part of every activist sex workers’ arsenal. It delivers some important perspective about sex workers’ rights as a labor movement by connecting the labor issues of garment industry workers and sex workers—who are so often the same people!

Moore’s reporting demonstrates that we have this global labor force of unskilled (mostly) women workers who are funneled from garment work to sex work and then back again into the factories, facing atrocious working conditions in both sectors because of global regulation, global markets, and what’s becoming the global criminalization of sex work.

Because of the conditions of today’s global garment market, these women make far below living wage working in factories which are often literally falling apart, having to make impossible quotas. So, often many of them quit and start doing sex work instead to try to earn that living wage. But the U.S. rewards countries for stepping up criminalization of sex work as an “anti-trafficking” effort, and so law enforcement and rescue orgs—who, as Moore noted and Red referenced above, often have garment industry bigwigs in their leadership and on their boards—help divert them back into “respectable” garment work. Moore even visited one anti-trafficking NGO which did garment work in-house, and the representative she spoke to said that the salaries they offered their workers were competitive with only the lowest paid regional sex work markets, at less than $2 a day.

I think this is one thing sex workers’ rights movements around the world need to start doing more of—thinking of the rights of sex working women even when they’re not doing sex work, or even just the rights of the classes of women who are likely to supplement their low earnings with sex work at some point. Because whether they’re working in brothels or factories or both, it’s often all just one group of people. These big garment corporations have obviously already noticed that, and that’s why they’ve put so much energy through anti-trafficking NGOs and anti-trafficking legislation into cutting off the more profitable avenue of sex work, to jealously safeguard that sweatshop labor pool for themselves. Imagine how powerful sex workers’ rights movements would be if we were allied with factory workers internationally! I’m reminded of how potent our labor rights message is when we do refer to these issues in our work, as in the slogan Thai sex worker organization Empower popularized, “Don’t talk to us about sewing machines, talk to us about workers’ rights.”

Red: The garment industry might be an excellent microcosm for labor history writ large, but somehow it never gets that focus. We hear a lot about the death of U.S. industry and unions, the movement of the auto industry and semi-conductors overseas, but not the garment industry so much. This was the first time I’ve seen the recent history of the garment industry explicitly outlined and mentioned. With the role it played in the history of labor organizing, of course it always gets a mention, a cursory brush by the Triangle Fire, a reference to “Bread and Roses”—but not very much more.

Yet, it was affected by the same factors that every other States-based industry was affected by, deconstructed by the same forces that attacked unions and labor rights across the country. And the rights that U.S. workers fought for over a century ago are still being fought for in the countries the industry relocated to, while the same tragedies (factory fires, massive underpay, union busting) play out in new factories.

Caty: Moore’s investigation of the true extent of the garment industry’s corrupt global hold is certainly masterful and potent in its concise execution. I was particularly struck by the material on thrift clothing. Considering the cultural cache thrift shopping has as a socially responsible way for hipsters to buy clothes, the short strip in which Moore revealed what a big, ruthless business thrift clothing really was shocked me. All the fossil fuels consumed and waste generated processing millions of pounds of used clothes and then selling them back to different developing countries than the ones they originally were made in, the way Goodwill underpays disabled workers by exploiting a Fair Labor Standards provision, the sheer amount of money the Goodwill CEOs make—it was pretty jarring stuff.

Threadbare also includes the sort of women’s rights analysis within labor scholarship we need to counteract economically oblivious neo-liberal feminist discourse. I like the book’s attention to gender themes throughout the analysis in the strips: the gender divide Moore keeps mentioning throughout between politician men criminalizing sex working women, politician men making trade agreements that affect the lives of millions of garment industry working women, factory-owning men making decisions which affect factory working women, etc. And the attention paid to the transphobic, misgendering practices of anti-trafficking NGOs working with trans women in Southeast Asia (they call them “transgender males”!); and how Christian anti-trafficking orgs promote misogynistic ideas such as abstinence education and “pious womanhood.”

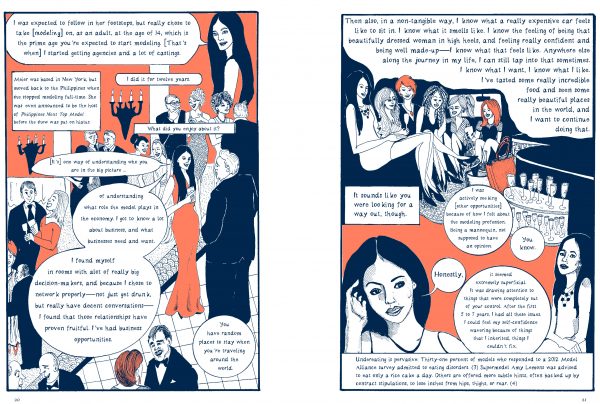

I also thought the connections made between models and sex workers in one of the first strips were fascinating. The way the model interviewed described her industry mirrored the cliched way ours is often depicted: a young girl getting corrupted, eaten up, and spit out by a cold, depraved big city and a ruthlessly competitive business, objectified for her looks. This is basically the Fallen Woman narrative to a T. She even told a story of a teenage model being stopped at the border on suspicion of being in a sex trafficking ring to drive it home.

I have to admit, even though I’d read some of the reporting that came to make up Threadbare before on sites like Alternet and I knew that Moore was a thoughtful and informed sex worker ally, the inclusion of the word “trafficking” in the book’s title made me nervous. The very use of that term so often indicates a simplistically anti-sex work abolitionist framework rather than an acknowledgement of labor abuses across industries. But the inclusion of things like that interview with this ex-model who was so obviously conflating her legitimized former profession with the worst stereotypes about sex work made me feel more confidence in the author. And I was completely won over when I saw that two entire strips were devoted to a beautifully illustrated interview with SWOP-Chicago sex worker activist Serpent Libertine on how anti-trafficking laws affect us U.S. sex workers, in which Libertine acquaints the civilian reader with recent sex workers’ rights history like Robyn Few’s founding of SWOP-USA and Stacy Swimme’s founding of Desiree Alliance, Emi Koyama’s analysis of Operation Cross Country, the closure of Young Women’s Empowerment Project, and Monica Jones’ battle against Project ROSE. The strip on Somaly Mam’s fraud and on anti-trafficking organizations’ predation on Cambodian sex workers, while also familiar material for sex worker readers, further proved that Moore used the word “trafficking” in order to deconstruct the common, narrow reading of the concept as only encompassing sex trafficking.

Red: However, if you, like me, spent over a decade smiling beatifically to forestall the order to “smile” from whatever asshole bouncer or club regular was walking by, then you, like me, understand the worry of laugh lines and crows’ feet and the necessity of not squinting or otherwise encouraging them! So, warning: as Caty mentioned, sections of Threadbare are written in a font that is literally one millimeter tall. I measured. Squinting was inevitable.

So be prepared. Get out your moisturizer and bring a magnifying glass.

Other than the unnecessarily wrinkle-inducing text sizing choices by artists Julia Gfrörer and Ellen Lindner, Threadbare is fantastic! All of the art is engaging and well done, the other artists don’t have the minuscule handwriting of Gfrorer and Lindner, and the information contained within is fascinating and utterly necessary to know. Everyone needs to read this, or at least have it read to them, story time style, by someone with good eyesight and a Botoxed forehead.

Makes me wonder… When you follow the money like this, you inevitably find gullible people, who think they are doing right for moral reasons, being conned by those who profit from the cause. Sometimes the profit makers even pretend to be the pious. So.. with the drug war a failure… one is left wondering how much of the new trafficking war is about someone, someplace, even when the garment industry isn’t included, is making money off of all the arrests. For example, since private jails still exist, even if they are now being very, very closely looked at, and even the government is calling to end them, it makes “economic sense” for these people to promote the false idea that they are “saving” people, by trading one prostitute, which they may not be able to keep in jail, for a revolving door of dozens of “traffickers”, i.e. clients. After all, the ones making money off it are almost certainly not so naive as to believe it will just stop, or become less common, the way the well meaning, but badly deluded, “moralists” are convinced is possible.

I’ve been wanting to read this book for a while and I’m glad it’s as good as I thought it would be. (Though I will buy an ebook for my ipad so I can enlarge until I can actually see it. Thanks for the warning.)

After reading “Model” by Michael Gross in college, I have always thought modeling was essentially high-end prostitution, with the added “benefit” of allowing teens to be legal victims of predators. I’ve yet to discover anything since that disproves this notion and I still wonder why no one tries to protect teen models in any way, but go apeshit over teen and adult sex workers (including and especially those who are working of their own volition). I’m so very glad this book looks directly at the modeling industry without any glamorizing of it.

A woman selling her body is a woman selling her body, right antis???

Wish they allowed it to be that simple, but you have those who would argue that how someone dresses is sufficient to make them somehow exploited (even when they are choosing the clothing themselves), and will stand by that view regardless of whether the person is 50, or 15, and… far, far, more people would argue that you are not really, “selling you body”, by their strict definition unless you strip naked, or, to an even greater extreme, actually involve sex somehow in the transaction. Like most moral issues, people like to think they are being nuanced by setting arbitrary standards, then ignoring the agency of the people involved, by insisting that any and all cases, no matter the age of the participants, is exploitative, in some case (which may be so, but.. so is every job. Its about how, and to what extent this is happening, and whether or not they are being robbed of choices.), or, alternatively, some similarly arbitrary case “doesn’t count”. So.. Of course most people don’t define modelling as exploiting teens, from which they need to be saved – it doesn’t involve porn or sex, so it can’t be “wrong” to treat them like interchangeable furniture, any more than it is to do the same to someone working for any other business.