While Western-led feminist groups such as Equality Now continue to conflate consensual sex work with trafficking and violence, where do sex workers themselves fit into concepts of feminism and gender equality, especially if they live in countries like India?

“When you are coming from a place like India, you have the whole caste system, stigma and discrimination to deal with. The paradigm becomes all inclusive. I wouldn’t talk about equality, I would talk about equity. You cannot talk about equality when you have spaces so filled with unequal distribution of wealth and privileges,” suggested Meena Seshu, founder of SANGRAM, a women’s organization in India that supports sex worker self-organizing, when asked her thoughts on the subject.

Seshu, who also works closely with the Asia Pacific Network of Sex Workers (APNSW), considers herself a feminist, despite run-ins with feminist groups in India who labeled her a trafficker: “In the initial stages, they weren’t willing to accept that sex work is not violence. If you are looking at sex work as violence, that stops the conversation with sex workers. Sex workers were not willing to talk about violence against them with feminists. They are against being victimized. With feminists, their narrative is about the victimization of women. Sex positive feminists were not willing to recognize the exchange of sexual services for money as part of sex positivism.”

In time, Seshu worked around these obstacles by simply listening to sex workers and supporting their work as a labor movement. She had previously worked with Bidi workers’ (cigarette rollers) labor movement and saw potential in helping sex workers organize: “So our fight was just to give sex workers a voice. The way we did this was to be very humble and say ‘look, we don’t know a damn thing.’ Previously, marketing targeted the client to use a condom. Self-determination worked, giving sex workers condoms worked.”

SANGRAM, founded in 1992, is so successful that it was listed as a best practice model by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on HIV prevention for working with sex workers. However, the situation became complicated when USAID stepped up its commitment to the the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Pledge, which required organizations receiving funds from USAID to sign a statement showing they did not “promote prostitution.” Seshu could not comply, as supporting sex work as legitimate labor was the backbone of SANGRAM. She declined the Pledge in 2005 and made plans to return funds for that year. What she did not count on was having her name brought up by former House Representative Mark Souder as a trafficker: “I started freaking out. Trafficking is a criminal offense. It was very, very messy and it lasted many months. The department in the U.S. that combats trafficking had labeled me a trafficker.”

Seshu also found her international travel was restricted and that she was denied visas for a period of several months: “Once when I was to go to Italy to attend a conference, they wouldn’t give me a visa. This happened during a six to eight month period. I found that when I applied to get visas to other countries, I was turned down. It kept happening. Finally, when I was invited to attend a U.N. meeting in the U.S. for U.N. General Assembly on HIV/AIDS, I was then given a visa. Later, the U.S. Embassy issued a clarification.”

Despite her difficulties, Seshu sees herself as relatively fortunate compared to activists who are or have been sex workers themselves. Current and former sex workers are subject to visa restrictions if they becomes known as such to authorities, depending on the country and the type of sex work. “Being denied a visa or labeled a trafficker is more serious for them,” she clarified.

In fact, one activist, a former sex worker who heads a sex worker-led network, was denied entry into the U.S. and experienced complications when traveling by air including being detained by US authorities for over two hours at a foreign airport. This activist chose to remain anonymous for fear of impacting future advocacy work and travel plans.

Melissa Hope Ditmore, a research consultant on gender, HIV and sex work, analyzed the impact of the PEPFAR pledge on organizations involved in HIV prevention efforts. Her research found that many organizations became leery of providing services to sex workers for fear of being labeled traffickers, which inevitably increased the stigmatization of sex workers. A Cambodian organization was closed down recently after being labeled a trafficker.

A handful of organizations challenged the constitutionality of the PEPFAR pledge, filing a lawsuit. One of those organizations was the Open Society Institute, which supports sex worker-led groups with grants. In July, the lawsuit was a success and the PEPFAR pledge was found to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Support for sex worker-led groups as partners in HIV prevention continues to build. The United Nations released two reports advocating the decriminalization of sex work in order to aid HIV prevention and reduce violence against sex workers. But the pushback from U.S.-based anti-trafficking groups which conflate consensual sex work with forced labor or trafficking continues. One group, Equality Now, led a campaign to bombard USAID Executive Director Michel Sidibe with e-mails, saying that the U.N. did not take “survivors of commercial sex work” into account when the research was conducted, despite one report accepting 680 submissions from a group of individuals and organizations which included many sex workers.

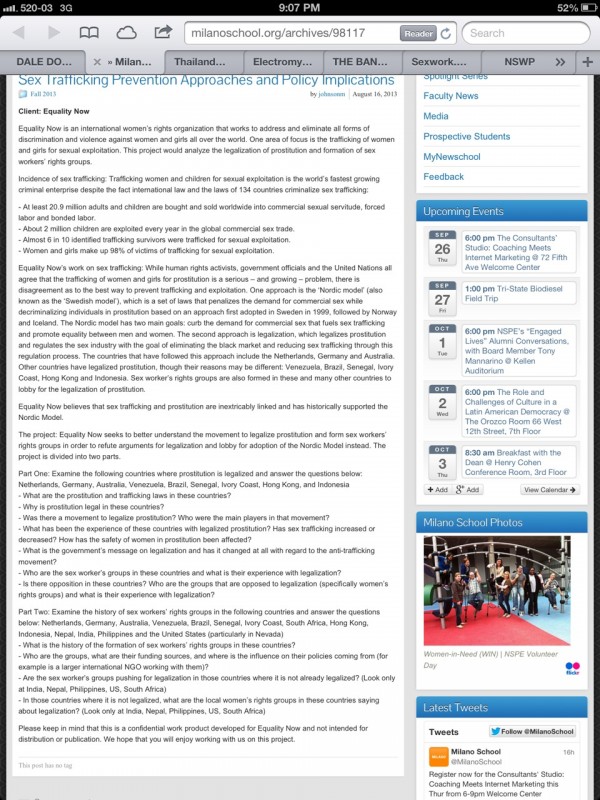

Equality Now also wants to recruit university students at Milano School of International Affairs in New York city to monitor sex worker-led groups, their supporters, and funders to “refute arguments for legalization.” Though the posting about this project, which appeared on the university’s website (likely in error), has since been removed, a screen shot was saved. In light of previous witch hunts against the supporters of sex workers, activists were appalled by Equality Now’s actions.

However, upon researching Equality’s Now’s own funders, things become yet more convoluted. Their annual report for 2012 shows that Open Society, the aforementioned pro-sex workers’ rights foundation which led the Supreme Court case against the PEPFAR anti-prostitution loyalty pledge, granted the NGO “over $100,000.” While Equality Now did not respond to requests for comment, nor did the Milano School professor that was to head the practicum, Open Society did. Sebastian Krueger, Communications Officer, Public Health Open Society Foundations at the foundation, reaffirmed the organization’s support for sex worker-led organizations and the decriminalization of sex work “to end violence and police abuse, ensure access to legal services, challenge and change laws and policies that harm health, and increase access to appropriate health services.” Krueger explained that the grant to Equality Now is “a two-year grant to Equality Now to fund a project in Eastern Africa securing rights outlined in the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights of Women in Africa. This specific project aligned with our goal to address violence and discrimination against women. “

This leads us to a question: if Open Society’s money is good enough for Equality Now, why aren’t their stated ideals to decriminalize sex work? And why does the NGO need to research the funders of sex workers when they are receiving money from the foremost leading foundation supporting them? In terms of funding, it seems that in the quest to end violence against women, it is a small world.

“The word ‘trafficking’ is such a red herring. Once you use it, the discussion is over,” explained Seshu. But the term is good for media sensationalism and it’s good for stirring up a campaign in which 1,000 emails flood the inbox of the executive director of UNAIDS.

Though western feminist groups might have a long way to go in recognizing the agency of sex workers, Seshu said feminists in India have started to understand sex workers’ point of view, though divisions remain: “[Some] feminist activists are analyzing sex work through the trafficking of minors. That complicates everything. Here we are saying they have to be separate. Adult trafficking is separate from child trafficking. What this does is infantilize women and girls. It also conflates consensual adult sex work with trafficking.”

In Equality Now’s proposed practicum, India was one of the countries listed to study further.

[…] decided it was best to return the funds. Previously lauded for her work, suddenly she found herself a target of anti-trafficking groups in the […]

[…] Equality Now, or Else?, Parker, Tits and Sass […]

[…] Equality Now, or Else?, Parker, Tits and Sass […]