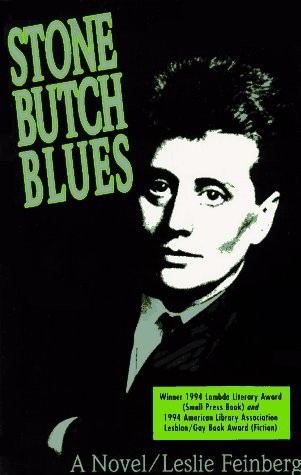

Trans/queer writer and socialist hero Leslie Feinberg died last week. The event rekindled my memories of squatting on the floor of Barnes and Nobles at the age of 17, reading the work zie’s1 most known for, Stone Butch Blues, a bildungsroman set in the lesbian working class bar scene during the Stonewall era. I was blown away by the novel and the way it brought together class politics, trans rights, and queer rights so explicitly. I’m not the only sex worker for whom the book was important. When I wrote to him about Blues, St. James Infirmary program director and sex working trans man Cyd Nova responded:

When I read Stone Butch Blues nine years ago I was just beginning to understand my gender as something other than female, while working as a stripper and seeing the club as the only place that I felt a sense of home…The way it illustrated feeling at odds with the world and the precise quality of needing to find a community who could guide you to your ultimate true self, navigating the path against the tide, was such an important read for me at that point…I would say that this book gave me some of building blocks to understand my desire to transition, before the internet was such a bastion of resources for trans folks.

In fact, my Facebook feed was awash with queer and trans sex workers linking to obituary pieces on Feinberg last week. So many of us could identify with hir writing about finding one’s people and working along with them in factories, bars, clubs, and the street to keep ourselves afloat. That’s why I was aghast at learning from The Toast that Stone Butch Blues is actually permanently out of print. (“How is that possible, when every dyke in America has at least two copies on her bookshelf?” inimitable Toast editor Mallory Ortberg opined.) But what I remembered most clearly was my rereading of the book in my mid-twenties, when I realized just how much of it was about valorizing femme sex workers as an integral part of the queer community.

The protagonist, young stone butch2 Jess, is mentored by femme sex workers while still in her teens. One of the first lessons she learns is to be gentle and respectful with street sex working femmes who may have just come from a bad call. Her first dance at a gay club is with a femme sex worker, and the first time she has sex is with a Black femme sex worker named Angie.

“Don’t be ashamed of being stone with a pro,” Angie tells Jess, “we’re a stone profession.” Both butches and sex workers suffer from a legacy of gendered and sexualized violence, and the implication in Blues is that they are counterparts, meant to protect and nurture one another. Feinberg writes about Jess’ relationship with femme stripper Milli: “We matched each other in nerve…For a stone butch and a stone pro to to survive, they have to tough it out with the world.” During Jess’ dance with street worker Yvette, her first dance with a femme lesbian, she notes that she:

…never ground [her] thigh into her pelvis…I knew she had been wounded there. Even as a young butch, that was the place I protected myself. I felt her pain, she knew mine. I felt her desire, she aroused mine.

Milli exclaims to Jess:

“That’s how pros and stone butches are. We just fit…You’re the only women in the world who hurt almost the same way I do, you know?”

Blues is punctuated by graphic, brutal police violence–strike breaking and bar raids. The cops rape and beat the butches and femmes alike, but Jess notes that they single out the sex workers specifically for even worse treatment:

Several of the femmes who the cops knew were prostitutes were getting roughed up and separated from the rest. I knew by now it would take at least a blow job to get them out of jail tonight.

So what Jess says she learns as a teenage butch is, “to fear the cops as a mortal enemy and to hate the pimps who controlled the lives of so many women we loved.” This sentiment is so different from most feminist queer texts of the period on the topic of sex work. Look at the context of that statement—this is no carceral feminism. It’s a working class, sex worker inclusive, trans/queer politic. This is hatred of pimps for being another system of abuse and control like the cops, not hatred of pimps qua pimps or hatred/disdain of these women’s choices—no, these are “the women we loved.”

But not all is rosy in the relationships between butches and femme sex workers, and Feinberg isn’t afraid to tackle whorephobia within the queer community in hir writing (even in discussing a period before “whorephobia” was even a word). Milli and Jess’ fight about her going back to work is familiar to any sex worker with a mostly accepting partner who still doesn’t quite get it. Milli quits dancing for a while after being beaten badly by a customer who happens to be an off-duty cop. Then, when Jess gets laid off from the plant, she considers going back to stripping. Jess is scared for Milli, who is justifiably annoyed by the idea of her lover telling her what to do, pointing out that Jess faces just as much danger in her temporary job as club bouncer. Jess yells:

“Ever since you met me you’ve been waiting for me to make one fucking mistake, say one wrong thing about you being a pro! …I never laid any bullshit on you about it. But every time we have a fight, you’re just lying in wait, hoping you’ll make me so mad I’ll make a mistake. Then you could leave..”

Feinberg deftly exposes her protagonist’s immaturity by making her behave the way we’ve all seen partners who want to remind us what saints they are in tolerating us and only calling us “whore” that one time do. Milli rails against Jess’ obliviousness:

“Did it ever occur to you that I might be uncomfortable at the bar?”

That had never occurred to me at all. “Why?” I asked, puzzled.

“Because there’s attitude towards us.”

“What are you talking about? Lots of women at the bars are pros.”

“They’re hometown girls who turn tricks to pay the rent. They’re ashamed of what they do. They aren’t into the life the same way as the rest of us…That’s your people, not mine. My people are the women I dance with. That’s who watches my back.”

Jess struggles to find a regular job before Milli has to return to dancing to sustain them, but as always, Feinberg allows an elder femme to have the last word: Justine at the bar exhorts Jess to “cut out all this drama,” and “grow up,” that if Jess doesn’t want to lose Milli she’d better lose her paternalistic attitude about her work.

Still, their relationship dissolves when Jess gets the notion to visit the club where Milli dances, fearing that if she doesn’t, she may never understand her. Unfortunately, Jess doesn’t consult Milli about this decision beforehand, and having Jess show up unannounced to gawk at her dancing naked decides Milli on packing her suitcase and leaving. But not before the two have a sweet farewell conversation in which Jess confesses that watching Milli work made her think about “how brave you all are…I couldn’t fight naked.” And unlike the cis straight guy we’ve all dated who swears upon breaking up with us that he’ll never date another hooker or stripper again, Jess sums up her breakup with Milli by telling her friend Edwin that “I really fucked up this time.”

Ultimately, Feinberg uses Jess’ foray into Milli’s club as a way to qualify sex work as part of a continuum of queer labor in a novel which is a chronicle of that labor, of butch dykes finding their place in unions, screaming at scabs and suffering work injuries. “This was, after all, a job,” Feinberg has Jess observe, “…it paid well for women who could take care of themselves.”

Milli teaches Jess an important lesson about relationships between marginalized people before she goes:

“Remember when you held me and told me you would protect me, you wouldn’t let anyone hurt me? …What you said wasn’t wrong, baby. That’s what everyone wants to hear when they’ve been hurt. The only problem was, you believe it yourself. You can’t protect me, sweetheart. I can’t protect you.”

Even though the world of Blues sets stone butches and femme sex workers up as natural partners, watching each other’s backs, Feinberg also introduces the limitations to this partnership through the canny practicality of a sex worker’s perspective. Feinberg is still a realist. In this world, there is no way love can always be enough among oppressed people. As Jess’ Black butch friend Edwin says about her relationship with femme stripper Darlene: “…it’s different between a butch and a pro. It’s love with no illusions.”

Even if this love is one without illusions, a love that can’t always prevail, it’s still an everlasting one. When reading this book for the third time to write this piece, I was amazed to discover just how much of a love song to femme sex workers it was.

In the wake of the injustice of the Ferguson decision, Marissa Alexander’s plea bargain after being charged with the crime of defending herself against domestic abuse, and trans and sex workers’ rights activist Monica Jones’ appeal this week against false charges of “manifesting prostitution,” it is more important now than ever for people to read Leslie Feinberg. Stone Butch Blues embodied intersectionality before it became a buzzword for a new generation of leftists, telling the story of a young Jewish masculine progressive working class person struggling with homophobia, transphobia, the Vietnam war, class struggle, and being an ally to her Black friends in the battle against racism. But it is especially important to keep Feinberg’s work alive because zie was one feminist, queer, and trans icon who was firmly on the side of sex workers.

1.I’m using the pronouns Leslie Feinberg’s longtime partner, Minnie Bruce Pratt, used for hir in her obituary for hir in The Advocate last week: she/her or zie/hir. I realize that The Advocate is far from an infallibly credible source on trans issues, but it is the last source for Feinberg’s pronouns from someone close to hir.↩

2.A “stone butch” is a butch who doesn’t receive genital contact during sex. It’s an older identity stemming from the mid-century lesbian bar scene, but a lot of people in the queer community, not just butches, still identify as stone today.↩

Phenomenal piece, I’ll bee forwarding this to a lot of sex workers, socialists, and queer folks . Thank you for taking the time and energy into writng such a loving and thoughtfull piece.

Great book

I read Stone Butch Blues in my early 20s, and ever since it’s been counted among my list of important reads. I can’t believe it’s no longer being printed! I better hang on to my copy!

Thanks for writing this piece. It was a wonderful tribute.

What a beautifully written and deeply felt tribute. Thank you.

I don’t think it’s out of print! I think Leslie was working to make it available to anyone for download before ze died.

it’s about $300 for a used copy on amazon! But I just found a website which has the whole booked scanned

http://www.slideshare.net/jordanlachance/stone-butchbluesvery-clean-rotated-copy

<3

Yeah, I linked to this in the piece!

Looks like it is out of print and very expensive now …

Wonderful piece, thanks for posting.