This is an adapted version of a piece that originally appeared on Suzy Favor Hamilton’s website. A couple of weeks ago, a Twitter follower gave me a heads up about an upcoming episode of Law & Order: SVU that appeared to mirror my story, at least the Vegas part. The preview I watched reinforced what was… Continue reading Huh, That Sounds Familiar—Law & Order: SVU

To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism In Africa (2016)

A version of this review originally appeared in issue 19 of make/shift magazine In March 2016, South African deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa made a historic announcement of a nationwide scheme to prevent and treat HIV among sex workers, proclaiming, “we cannot deny the humanity and inalienable rights of people who engage in sex work.” Though… Continue reading To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism In Africa (2016)

Uptown Thief (2016)

Slam poet and African American studies professor Aya de León’s new novel, Uptown Thief, is every activist sex worker’s fantasy: her protagonist Marisol Rivera is a women’s health clinic director by day and an escort agency manager and expert safe-cracker to fund that clinic for survival workers by night. True, any enterprising hooker who actually… Continue reading Uptown Thief (2016)

We Deserve Better: Reflections On The War On Backpage

It’s happening again. I remember the drop in my stomach as my browser opened on the homepage of MyRedBook in 2014 and I saw the emblems of the FBI, DOJ, and the IRS occupying a page which used to host an escort ad, review, and forum website used by thousands of providers across the West… Continue reading We Deserve Better: Reflections On The War On Backpage

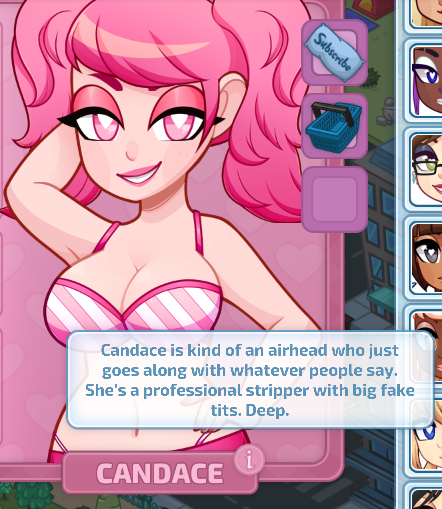

Huniecam Studio (2016)

Every time I play a video game that includes sex workers as characters, all I can think about is how great it would be to be seen as a person. Usually, sex workers in games are just toys for the player’s entertainment or tools to deepen the protagonist’s story. Either way, they’re only there intermittently,… Continue reading Huniecam Studio (2016)