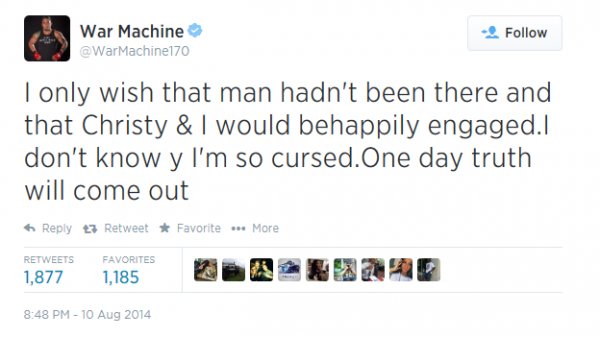

“Don’t hit women or whores” reads an oh-so-helpful comment under one of the many reports of the brutal assault and attempted rape of porn actress and dancer Christy Mack by her ex partner, War Machine (formerly known as John Koppenhaver), this past week. And that’s one of the nice ones. Most of the not-nice ones start with “what did you expect?” and get worse from there. Koppenhaver himself seems to see his role in the attack as a tragic victim of fate, a “cursed” man who had hoped to be engaged to the woman he broke up with in May, whose house he broke into in August.

While, in the face of the graphic and horrific story that Mack released, Koppenhaver’s view seems woefully out of touch with reality, the truth is, he’s right to predict sympathy for himself. Assaulting a sex worker, especially one that you once deigned to be in a relationship with, is viewed as pretty understandable. Just by watching TV or using the internet (ever), how many hundreds of jokes and not-jokes did Koppenhaver encounter excusing and encouraging him to do just that? It might be tempting, for the sake of our views on the state of humanity, to label his on-the-run tweets as a disingenuous ploy for public understanding, but I believe it is the less likely explanation of the two. What reason have we to believe that Koppenhaver was special, that he was somehow immune to the prevailing cultural narrative about the worth of those who do sex work? Why wouldn’t he think of himself as a lamentable casualty of an unfair system?

When dehumanizing jokes about sex workers get made, when we’re portrayed as disposable by the media, when our deaths, disappearances and assaults aren’t investigated by the police, when our attackers go free, it’s not just that our feelings get hurt. The problem is not just that justice isn’t served in any particular single instance. The problem is that every one of these messages has a ripple effect outwards — that sex workers are fair game, that hurting us does not come with consequences attached, that, even if you do catch some heat, plenty of people will say, “Well, it’s understandable.” That message goes out, loud and clear, to every would-be predator, to every person carefully choosing their victim, to every person deciding whether and how much to control their anger — and that answer will certainly be changed by who will be on the receiving end of that anger. And this lack of care for us doesn’t just make attacks on sex workers more likely, it makes them more dangerous. Lundy Bancroft, author of Why Does He Do That?, a manual of information gleaned from 15 years of working with male perpetrators of intimate partner violence, has a lot to say about the mechanisms that lead to violent abuse, namely:

While a man is on an abusive rampage, verbally or physically, his mind maintains awareness of a number of questions: “Am I doing something that other people could find out about, so it could make me look bad? Am I doing anything that could get me in legal trouble? Could I get hurt myself? Am I doing anything that I myself consider too cruel, gross, or violent?”

A critical insight seeped into me from working with my first few dozen clients: An abuser almost never does anything that he himself considers morally unacceptable.”

And with every casual and serious instance of whorephobia that passes unchecked in the public sphere, society pushes the bar of what is morally acceptable when wielded against us farther, making it less and less safe for sex workers to trust their partners. Later in that same section of his book, Bancroft describes another conversation he frequently had with the abusers he worked with:

“How many of you have ever felt angry enough at your mother to get the urge to call her a bitch?” Typically half or more of the group members raise their hands. Then I ask, “How many of you have ever acted on that urge?” All the hands fly down, and the men cast appalled gazes on me, as if I had just asked whether they sell drugs outside elementary schools. So then I ask, “Well, why haven’t you?” The same answer shoots out from the men each time I do this exercise: “But you can’t treat your mother like that, no matter how angry you are! You just don’t do that!”

If mothers are off-limits, and partners aren’t, then sex workers, whether or not they are partners (or exes, because breaking up with a violent asshole doesn’t make you safe), appear to be in a special category of “available for violence.” And it’s something that every sex worker with a partner has to think of, when they have an argument, when they decide what to share and what to hold back about their day at work, when they decide how to have the breakup conversation. Because we know that, no matter how lovely, how supportive, how kind and nonviolent our partners may be, they are that way in spite of societal messages, not because of them. And so therefore, it is only their own good sense and compassion that protects us from whorephobic violence from the people closest to us. There is no permanent escape from the knowledge that, if our partners one day turned on us, some not-so-small, not-so-insignificant portion of the population would shrug their shoulders and say, “Well, what did you expect?” And we have to live every day knowing that our partners know this too—they have to know it. It’s unmissable.

Violence against sex workers doesn’t just rip apart the lives of those of us who are victims of it. Every time a story like this hits the news cycle, every time we watch people with no connection to the us to or the victims casually mull over exactly how deserved the violence was, we assess, again and again, how that could happen to us, if that could happen to us, and what would happen afterward if it did. The impact of this is more insidious than simply that we are more likely to experience violence. This hurdle of trust isolates us — makes it that bit harder to trust the partners we have, makes it that bit harder to reach out to find people to share our lives with in the first place. It raises the wall between sex worker and civilian that keeps us apart, and increases the danger thereby. Because sex workers don’t become humanized in the public eye by wishing and politely asking for it. An essential part of that process is building our families, our networks of friends and becoming part of communities that care for us and value us. And whorephobic violence, as it prevents us from doing that, as it causes us to consider with fear when we reach out to people, is nothing less than terrorism.

Yup. It’s regular victim-blaming x 1,000,000 when it comes to sex workers.

“…we assess, again and again, how that could happen to us, if that could happen to us, and what would happen afterward if it did.”

Yep.

I appreciate the thought that went into choosing pics to accompany this article, btw.

” Every time a story like this hits the news cycle, every time we watch people with no connection to the us to or the victims casually mull over exactly how deserved the violence was, we assess, again and again, how that could happen to us, if that could happen to us, and what would happen afterward if it did. The impact of this is more insidious than simply that we are more likely to experience violence”

All of this, for sure. Which is not to remove Christy Mack from the center of this at all. It’s all about her, and I wish her well and hope her community is supportive, as much as I hope the wider community can support each other through these awful thoughts.

What I wrote on Facebook:

I am choosing to share this article, cautiously because in the context of Facebook sometimes talking about how fucked society can be, can overwhelm in a way that does not help us build and grow, but I want people to read it because it talks about how the permission for whorephobic (and by turns racist or transphobic) physical violence is created. I am so grateful that I exist in a community that by large does not view my sex worker status as a reason to dehumanize me, but that does not mean that I have not been effected by this sociocultural measure of worth. I have absolutely been violently sexually assaulted by clients and despite the activism, the support, the culture I exist in – afterwards I felt like even if I didn’t deserve itI should have expected it, and felt little to no agency in seeking any kind of justice, legal or otherwise. When my friends and partners responded by caring for me, it was gratefulness that I felt that they took me seriously, instead of an expectation that that was what people do when you get hurt. This is not intrinsic to sex work. Its not that if you have sex a certain amount of times, eventually one of those times you are bound to get raped. This is because our society teaches people that those who get paid for sex are acceptable targets for violence. We are told by abolitionist rhetoric like ‘End Demand’ that the desire to cause violence to sex workers is the same as the desire to pay for sex and I need people to understand that that is not true. Stopping violence against sex workers does not stop at the behavior of clients, it includes every person in society who through words, actions, and reactions to news stories like these, pardons the behavior of those who abuse us.

I must read this book, by Lundy.