Imagine a city so bleak, so hopeless, so full of darkness, that only criminals and social rejects have a fighting chance to survive living there. Imagine villains so desperate, so foul, so vile, that the ugliest death for them still wouldn’t feel like justice. Now imagine heros who are so full of vice, rage, and demons that they are not much better than our villains. Picture a city that doesn’t have a violent underbelly, because its entirety is a violent underbelly. This is the setting Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller have built for us with Sin City and its sequel, Sin City: A Dame To Kill For. Based on Miller’s comic book series of the same name, the two have constructed a nightmare town that is terrifically gory and hellbent on destroying every person who enters it.

Imagine a city so bleak, so hopeless, so full of darkness, that only criminals and social rejects have a fighting chance to survive living there. Imagine villains so desperate, so foul, so vile, that the ugliest death for them still wouldn’t feel like justice. Now imagine heros who are so full of vice, rage, and demons that they are not much better than our villains. Picture a city that doesn’t have a violent underbelly, because its entirety is a violent underbelly. This is the setting Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller have built for us with Sin City and its sequel, Sin City: A Dame To Kill For. Based on Miller’s comic book series of the same name, the two have constructed a nightmare town that is terrifically gory and hellbent on destroying every person who enters it.

The characters that seem most equipped to survive Sin City are its sex workers. (Spoilers ahead.)

Miller has frequently been described as a misogynist for the way he writes his female characters. This is true for the most part; the films are misogynistic for a variety of reasons. Oddly, one way critics have supported this assertion is by citing that Miller often makes his female characters sex workers. Because, apparently, if one of your female characters is a street worker or a stripper, you must hate women. (Does that mean if she’s a dentist or a farmer you love women?). I’m not sure how that makes sense, so if a feminist film critic is reading this, feel free to explain in the comments.

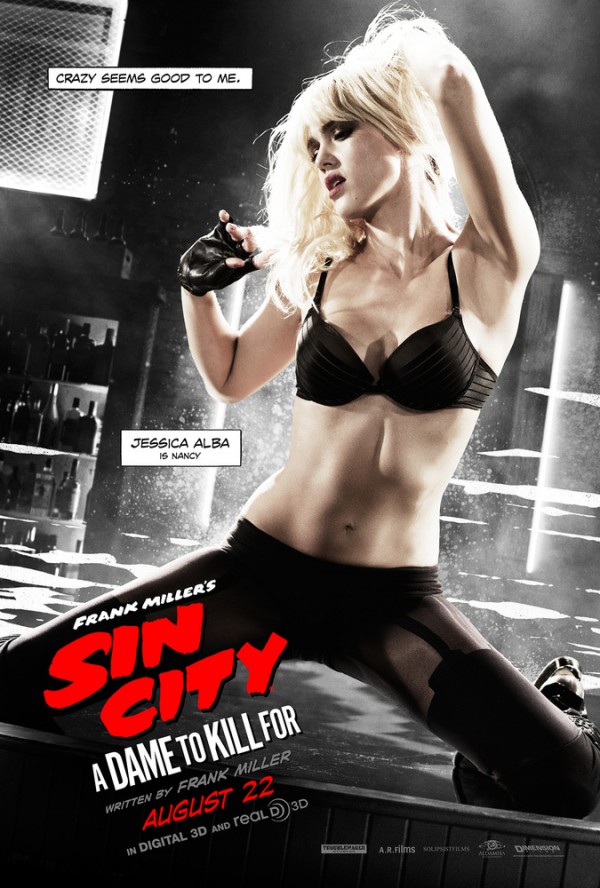

To be clear, the sex workers in both films are completely stereotypical, unoriginal archetypes. Think damsels in distress and black widows, but with less clothing. The characters are so cliched, in fact, that one would assume they’re meant to pay homage to their noir predecessors. Nancy (Jessica Alba) is a stripper with a raging case of Daddy Issues. Goldie and Wendy (Jamie King) are twin street workers; one of them ends up dead by the hands of a cannibalistic serial killer. Gail (Rosario Dawson) is my favorite— a street worker-dominatrix who is the unspoken leader of the sex workers that police Old Town, Sin City’s red light district. Miho (Devon Aoki/Jamie Chung) is a part of Gail’s entourage; she’s an unapologetic assassin. Becky (Alexis Bledel [Rory Gilmore!]) is a young, childlike street worker who ultimately double-crosses the women working in Old Town.

The films’ palettes are intentionally stylistic, only black and white with a rare splash of color for emphasis. They reminded me of the way my mind animates a graphic novel as I read it. They are formatted in a series of vignettes. Each vignette details a different character’s independent story and is narrated by the story’s protagonist.

Goldie’s storyline was the most problematic. She’s a beautiful escort who spends a whirlwind night with Marv (Mickey Rourke), a binge-drinking Captain Save-A-Ho with serious anger control issues. In the morning, he finds her dead. Guess who killed her? A prenaturally strong serial killer named Kevin (Elijah Wood); he’s got the heads of sex working women mounted across the walls of his hideout. Goldie’s death seemed like the sex workers’ version of Women in Refrigerators Syndrome, the comic book trope in which female characters are swiftly killed off for the sake of their male counterpart’s character development. Marv doesn’t have a great reputation in Sin City, and he looks pretty guilty already. But he loved Goldie, possibly because she’s the only woman that ever touched him, and vows to find her killer. With the help of her twin, Marv finds Kevin and, of course, avenges Goldie’s death. He ends up dead later.

The most delightful scenes of both films occur in Old Town, the red light district of Sin City. Old Town is the street workers’ version of the Wire’s Hamsterdam: the cops stay out, and the sex workers are in charge. And they have an honor code: Do not fuck with the sex workers of Old Town lest you be tortured and dismembered. Gail functions as the den mother of Old Town. A lithe Rosario Dawson brings an irresistible fire to her character, merging cockiness with acumen. When babyfaced Becky is threatened street-side by Jackie Boy, a no good would-be pimp, Gail sends sex working assassin Miho to slaughter him. They teach Jackie Boy the rules: do not fuck with the sex workers of Old Town. But wait—Jackie Boy’s killing was a set up of epic proportion that will ultimately compromise the security the sex workers have created in Old Town. No big deal though, they got this. What follows is a literal bloodbath of sex workers gone militant. They have guns. And swords. It’s magical. Is Old Town an allegory for decriminalization? Probably not, but we wouldn’t have to worry about hordes of murderous sex workers running the streets if the work were legal. Just saying.

The Old Town workers play a pivotal role in the second film as well. Gail and Miho help storm Ava Lord’s (Eva Green) mansion to kill mob boss Wallenquist (Stacey Keach). Miho has some show stealing scenes in the second film. It’s unfortunate that Miho doesn’t ever speak in either films. We’re only allowed a small yet vital glimpse into her backstory. Her presence in both films was commanding; she deserved a more fleshed out examination.

Nancy’s storyline is the most ridiculous, even accounting for the absurd plot contortions that always litter the noir genre. As a small child, Nancy was kidnapped by Senator Roark (Powers Booth) at the behest of his nephew, Roark Junior (Nick Stahl). Roark Junior is a sadistic pedophile who has some gross, rapey plans for Nancy. Luckily, Detective John Hardigan (Bruce Willis)—the last uncorrupted cop on the force—rescues her. His rescue attempt involves maiming Roark Junior in a satisfying act of brutality: He gets de-dicked. The bad news: Hardigan is framed and sent to prison. By the time he’s released, our precious Nancy is all grown up. She’s the most popular exotic dancer at Sin City’s strip club. I’m certain the writers did not mind finding a reason to give Jessica Alba a pair of chaps and a lasso. Nancy has been waiting her entire adult life for Hardigan’s release because, apparently, she fell in luuurrrvv with him somehow (Holy Daddy Issues, Batman!). It doesn’t take long for her to get kidnapped again by the Roarks after the two are reunited. Don’t worry though, Hardigan saves her. But he ends up dead too.

In the second film Nancy has become bitter and unhinged. She’s definitely not adhering to the sad stripper trope; she’s very angry. Nancy starts drinking, which leads to an unhealthy fixation, which leads to insanity, which leads to a sweet revenge story. Nancy’s officially done with men, and done with dancing. She’s cracking, but that’s ok because a diagnosis of “crazy” is an industry exit plan which actually seems logical in the Sin City universe. Spoiler! Nancy kills the films’ worst bad guy.

My feelings about the sex workers’ depictions in Sin City and Sin City: A Dame to Kill For are conflicted. While the movies’ predictable characterization of sex workers are relentlessly sexist, they’re not whorephobic. The protagonists never shame the sex workers, or encourage them to find new work, or seem threatened by what they do. One curious observation I made is that every man that attempts to “rescue” a sex worker inevitably ends up dead. Still, the films’ portrayal of sex work isn’t subversive; many of the same old sex worker tropes are simply rehashed with slicker packaging.

The sex workers play a larger role in the first film than the second, but their roles are essential in both. It’s unfortunate that their storylines are so dependent on the men. A sex worker-specific vignette would serve the Sin City franchise well. They’re beautiful women that are so much fun to watch. Allowing them comprehensive, dynamic personalities would have made their adventures that much more compelling. If you absolutely can’t stomach worn-out sex worker clichés filtered through the male gaze, then skip these movies. But if some armed and dangerous sex workers sound like a lot of fun to you, then these films are definitely worth exploring.

So so agree with this critique. I was actually thinking about writing such a piece myself except analyzing extreme metal music, why despite its blatant and promiscuous misogyny it still felt like a better fit for me than the anti-sex work brands of “feminist” music I was told I should like. The women who wound up being role models to me were sex workers, transgender, drug users, and almost all had criminal records of some kind. But because of the complete no-go terrain of sex work and violence that didn’t fit a clear normative self-defense explanation, these women did not feel there was a place for them in feminism.

Emma, if you ever have time to write that metal piece for us, please let me know! Sounds like it’d be a very important read, and we definitely don’t have enough music analysis on TAS.

Loved this. I’d kill for a whole vignette around Gail running shit.

“Because, apparently, if one of your female characters is a street worker or a stripper, you must hate women.”

That’s not the criticism I’ve seen of Miller – it’s more like, “if almost every female character you write is a sex worker, and the few who aren’t are two-dimensional sex objects, you probably hate women.”

In the setting of Sin City it makes a kind of sense to have a lot of street workers, but he’s also written two versions of Catwoman – one dominatrix, one escort agency manager – retconned Black Canary’s story so her costume is the uniform of the strip club she bartends at, and regularly designs covers which reduce superheroines like Wonder Woman to their ass alone.

I get the whole male gaze critique but I generally cannot understand why writing all your characters as sex workers is anti-woman or even any-feminist. Isn’t the goal to produce as many representations of women as possible such that our cultural depictions of women in film and other media are challenged? And though I’ve not seen the film, it sounds like it passes the Bechdale Test? If so, it’s a more transgressive flick than most.

If they are all in sex work yet that is their ONLY defining characteristic, I’m not giving him the credit of assuming he wants our stories to be told. It’s an excuse for limiting all female characters to be defined by sex and their sex life, because if they’re sex workers they must not have anything else going on, right?

I refuse to settle for representation that is no more than the job itself.

I’m a fan of the Sin City graphic novels, and one of the stories is all about the whores. Specifically it’s Miho tracking down a guy who killed a whore accidentally (drive-by failure) when she was on the phone to her girlfriend. She destroys them perfectly. It’s pretty great, because the men almost die thinking that it’s a hit from another family, when really, their actions have unforeseen consequences that they can’t run away from. I loved it.

I also don’t remember where I heard it, but Frank Miller described Kevin and Miho as both being supernatural beings; Kevin basically being a devil and Miho being Sin City’s avenging angel. So that’s cool too.