Bareback sex feels fucking amazing.

Bareback sex feels fucking amazing.

I know, we’re not supposed to talk about that. We’re not supposed to talk about bareback fucking without following it up with that ubiquitous “but use a condom!” statement. However, many communities face significant barriers to condom use and have very legitimate reasons for foregoing them—and these are the communities whose voices have largely been excluded from broader conversations defining “safe sex.”

That’s a big problem. As harm reductionists and sex educators, we can’t talk openly about what people are really doing behind closed doors. We aren’t supposed to legitimize sex without a condom as an option, or rather, we aren’t supposed to acknowledge that it may be the only option for many marginalized people. And that’s exactly the kind of dishonesty that allows HIV stigma to proliferate.

As an HIV counselor and longtime public health activist, as well as an ex-sex worker and IV drug user, I want this attitude to change. We need to re-open the conversation around what safe sex means in America and internationally, because while condoms can be an excellent means of STI protection, they are by no means a realistic option for every person in every situation. And sex workers in particular need to be involved in this conversation, since it is the most marginalized groups among us—drug-using sex workers, sex working trans women, street workers, sex workers of color, and people who fit into many or all of the above categories—who most often find ourselves in situations in which providing bareback services is our only option if we want to make a living.

So what does it mean to talk about “safe sex” in 2018, 38 years after the first cases of HIV emerged in the United States? Who is not included in our condom-centered discussions of safe sex? And why is it important to open the door to destigmatizing a potentially “risky” sexual practice?

So what does it mean to talk about “safe sex” in 2018, 38 years after the first cases of HIV emerged in the United States? Who is not included in our condom-centered discussions of safe sex? And why is it important to open the door to destigmatizing a potentially “risky” sexual practice?

HIV/AIDS was known pejoratively as “Gay Man’s Cancer” when it first appeared in the U.S. in the early 1980s. Thought at that time to only affect gay men, injection drug users, and people from the African subcontinent, HIV was highly stigmatized right from the start. Though we know that this is absolutely not the case in 2018, HIV/AIDS is still highly associated with being a gay man, being African American, being an injection drug user, or living in a so-called “developing nation.” This historical lack of knowledge and understanding around HIV modes of transmission and effective treatment methodologies lead to a fear-based and highly reactive public health ideology regarding “safe sex.” This was arguably understandable (though not excusable) at the time, given the lack of scientific developments around HIV/AIDS and the real need for government and public health departments to eventually create some sort of plan to address prevention.

But while this knee-jerk reaction may have made sense in the 1980s and 1990s, we now have a very sophisticated understanding of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus which wasn’t possible 20 or 30 year ago. The CDC recently released a report stating that being undetectable (in terms of one’s HIV viral load) is equivalent to being untransmittable. Meaning, if a person living with HIV has an undetectable level of the HIV virus in their body, then they cannot transmit the virus to others. According to Dr. Joel Gallant, M.D., M.P.H, quoted in HIV/AIDS-focused online publication The Body, most people who are living with HIV, know their status, and adhere to treatment methods “almost always” become undetectable within a six month period (barring several variables). Becoming undetectable is not some rare anomaly but rather a very common and probable outcome for people living with HIV who are taking antiretroviral medications (ARVs) today in the U.S.

This statement by the CDC is a major breakthrough. Why are we not talking about it more and revisiting the impact this has on our previous practices and understandings around HIV prevention? Is it because we’re scared as a culture that by saying condom use may not be the sole effective means of HIV prevention then we are thereby endorsing “unsafe sex?” Are we afraid to acknowledge the fact that some people are unable to or just choose not to use condoms and that some of their reasons for doing so are valid? This inability to reopen a critical dialogue only further stunts harm reduction conversations and stigmatizes people living with HIV by maintaining an outdated prevention mentality.

Why aren’t we supporting people living with HIV by opening up this dialogue? Because it’s going to be controversial? Because it’s taboo to talk about? If you want to stand up for sex positivity, sexual health, and people living with HIV, then get over your discomfort. Talking about sex from a new, open perspective is something that we must brave if we want to continue to develop the conversation around HIV and “safe sex.”

What does “safe sex” mean, anyways? Well, two or three decades ago, it mostly meant sex with condoms at all times, for everyone, no matter what. Now, I want to be clear that I am not arguing against condom use, nor am I intending to minimize the seriousness of contracting or living with HIV. Condoms are still one of the most effective methods of STI prevention, when available, and can be a great option for some people. Recently, a strain of gonorrhea has emerged—often known as “super gonorrhea”—which is resistant to the cephalosporin class of antibiotics, the recommended foundation of treatment for such STIs. Condoms are a first line of defense in protecting against these kinds of sexually transmitted infections, especially when they become antibiotic resistant and difficult to treat.

I am not suggesting we should all go out and have sex willy-nilly without any thought to health consequences; I am stating that a condom is not the only means by which one can take steps to care for one’s sexual health. Oftentimes, those steps are not composed of a singular method of protection, but a unique, personally tailored combination of preventative measures which can yield the most success for an individual. And since the HIV/STI prevention and intervention measures we have available have developed over time, so too should we develop our approach to “safe sex.” Nowadays, we have PrEP, or Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, which is a pill widely available (through harm reduction organizations and scholarships the pharmaceutical company provides) that one can take on a daily or semi-daily basis to prevent HIV. Post Exposure Prophylaxis, or PEP, is the same antiretroviral medication as PrEP (Truvada), and works similarly—however, is taken after one thinks they may have been exposed to HIV, within a 72-hour period. Now, these treatments are not for everyone, but as harm reductionists, it’s important to let communities we work with know that they exist and can be highly effective in HIV prevention.

In my experience as a public health employee, men who publicly identify as gay (not including men who identify as straight but have sex with men) most always know what PrEP and PEP are, how they work, and where to get them. That’s great. But my experience with sex workers (especially survival sex workers), IV drug users, and individuals who identify as straight is that these populations rarely know about these medications.

Besides pharmaceutical options, which may be hard for some communities to adopt, there are more homespun sexual harm-reduction options which marginalized people have developed over the years, such as those outlined in harm reduction elder and ex-sex worker Synn Stern’s seminal “Tricks of the Trade” street work harm reduction manual. Some of the suggestions Stern makes are to change underwear daily, or at least turn them inside out; to make sure to keep the mouth, genitals, and anus well lubricated before and during sex; to not brush teeth or use alcohol-based mouthwash before an encounter, as they can cause small tears in one’s gum tissue, thus leaving one vulnerable to infection; and to try not to shave the groin area or anus right before sex as similarly, small cuts on the skin can leave one more susceptible to STIs and skin infections like Staph and MRSA. Additionally, though “female” (receptive) condoms have recently become prescription only, they can often be found at free clinics and can be inserted in the anus or vagina before one goes out on the track to work, giving one more control over one’s own body during sex.

Some of the other suggestions Stern outlines can potentially help give street-based sex workers more leverage during negotiations, such as knowing what you will and won’t do before talking to a client, and giving clients a time limit from the beginning, as some tricks may become violent if they can’t get off in a reasonable amount of time. Other strategies include deciding on the hotel or other session location oneself and not leaving it up to a client to decide. More leverage in negotiations in general can often mean more leverage around safer sex techniques and harm reduction methods. These strategies can easily be extrapolated to the general non-sex working public as well, especially for cis women, transgender individuals, and queer-identified people, who are more likely to encounter sexual violence than a cis white heterosexual man, and thus more likely to find themselves in situations where safer sex decisions are taken out of their hands.

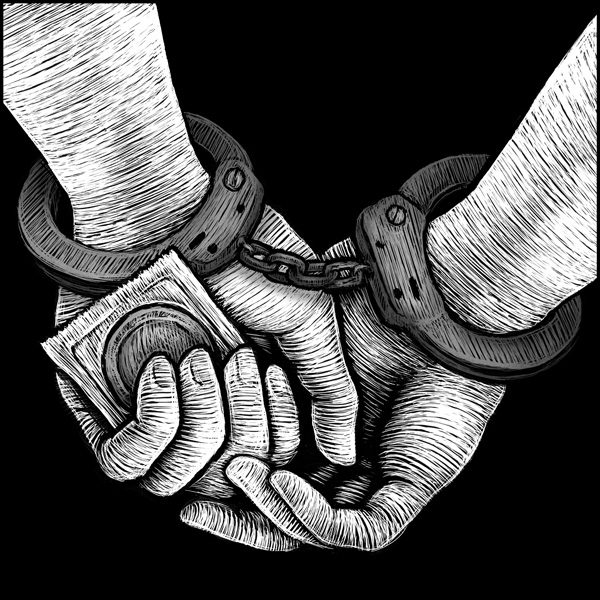

When I was a sex worker, I never used condoms with clients. You see, I was a survival sex worker and not only did I not have money for condoms, but sex workers all over the U.S. have historically been arrested just for carrying condoms. Survival and outdoor sex workers are particularly vulnerable as we have less control over our environment than do indoor sex workers or upper-echelon escorts. When one does not have a safe place to work with a client, then having sex in a car, bushes, an alleyway, etc. can make it more difficult to negotiate condom use. Additionally, both indoor and outdoor full-service sex workers can and usually do at some point run into clients who demand sex without a condom and are willing to pay a premium for it. A high-income online escort may have the financial leverage to decline to work with such a client, but when someone is hungry, cold, tired, in withdrawal, and just desperate for money this is a luxury they literally cannot afford.

This problem in practicing sexual harm reduction is similar to the harm reduction problems often faced by people who use drugs in the context of criminalization. For example, I used to slam heroin with dirty needles because I didn’t want to get shit from an asshole cop for carrying paraphernalia. Homeless IV drug users in particular are at increased risk of being harassed and unfairly searched by police, so trying to hold on to a supply of clean needles, cookers, cotton, condoms, etc. is not only unrealistic when one is living outdoors but can also be dangerous if the police decide to give you a hard time. When harm reduction and sex education dogma does not acknowledge these kinds of realities, it becomes a neoliberal ideology that shames people for not minimizing STI risks in certain approved ways, even while those risk minimization methods are inaccessible to them.

Sex workers and drug users, as well as low-income people, people currently living with HIV, transgender individuals, homeless people, and people of color in general are mostly left out of the current conversation around safe sex. The unique barriers and stigma these individuals experience are not taken into account in mainstream sexual health narratives. And that’s not fair. Condoms aren’t realistic for every person in every situation. Get over it. Nor might a couple deem them necessary if, for example, one or both partners are living with HIV and have an undetectable viral load, or if one or both partners are on PrEP. In this new age of “U=U” (undetectable equals untransmittable), we need to re-evaluate what we want HIV prevention efforts and education to look like, especially when working with vulnerable populations and people already living with HIV.

We need to have the balls as a country to revisit the conversation around what it means to have sex “safely.” The formula for a safe sexual encounter should not be a static one, but an ongoing, ever developing, and highly inclusive conversation. We need to consider that safety as we define it now is more available for some communities than others. And we as public health providers need to begin to create a space where people can feel safe discussing stigmatized sexual behaviors. Yes, that does mean a delicate balancing act between creating supportive, non-judgmental space while also working alongside people to determine and reinforce what health and safety could look like for them. But this is a necessary discomfort we need to bear in order to effectively work to create safe spaces for people to be honest, authentic, and truly capable of protecting their health. If people can’t be any of those things with medical providers and public health workers, then what ideologies are we really dismantling and which are we upholding?

iknow dangerous but bareback onky for me

Brilliant commentary. I think this hits the nail on the head: “When harm reduction and sex education dogma does not acknowledge these kinds of realities, it becomes a neoliberal ideology that shames people for not minimizing STI risks in certain approved ways, even while those risk minimization methods are inaccessible to them.”

The reality of bareback sex belies the myth of choice that so many in the sex positive crowd like to impose on sex workers. We’re encouraged to write off sex workers for whom consistent condom use just isn’t a viable option by saying “that’s not sex work, that’s trafficking,” or “the VAST MAJORITY of sex workers would never work without a condom, we’re experts on safer sex, that’s what makes us better than hookups,” or “sex workers are not vectors of disease,” or “survival sex workers face that problem, but the VAST MAJORITY of us are here by choice.”

And it’s not that those statements aren’t true, at least some of the time. But when they’re pushed and pushed, to the exclusion of ever thinking about or planning, collectively, for the reality of barebacking, they harm us. I appreciate the courage you’ve shown by opening discussion of the taboo.

Thank you so much dear!

Laura, another thought provoking opinion piece.

Condoms don’t always prevent HSV2+ infections. Maybe you can write about that some time?