Toronto’s Migrant Sex Workers Project, “a grassroots group of migrants, sex workers, and allies who demand safety and dignity for all sex workers regardless of legal status”, was co-founded last May by Elene Lam, Chanelle Gallant, and Tings Chak. Lam, who moved to the area from Hong Kong two years ago, saw a gap in local activism where migrant sex workers were concerned,”because there is a strong sex worker movement and strong migrant movement but no migrant sex worker movement.” She began organizing with the Chinese Canadian community, specifically with MSWP’s sister organization, Asian and migrant sex worker support network Butterfly. Soon, longtime sex worker activist Gallant began collaborating with her—”I really wanted to support the work that she was doing…she moved to Toronto and with pretty much no resources and no connections just started making all these things happen, in terms of creating support for migrants in the sex trade here.” With the aid of Tings Chak of Toronto’s No One Is Illegal, they solidified their burgeoning work into the MSWP. This summer, Kate Zen, a sex worker activist with years of experience organizing in the informal labor sector, joined them as a member.

In the context of coverage of the “migrant crisis” all over the global media, I felt it was more important than ever to learn about migrant sex worker activism. I spoke to Lam, Gallant, and Zen over a video call. The transcription below is an edited and condensed version of that conversation. The second part of the interview is here.

How does the displacement of millions of refugees due to war and economic inequality, which the media is calling “the migrant crisis,” affect your organization’s work? What would you want to see the North American sex workers’ rights movement do in response to the crisis?

Elene Lam: So I think instead of starting with the crisis recently, we need to know actually, that people start to move to different places since we have the history of the human being. I think the “migrant crisis”, this term is used to create a panic and fear of people, to justify how they screen the migrants and stop the migrants. I think that when you see the history—that people migrate because of economic reasons or war—this always happens. But you see more recently—especially [in] the Global North—they use whatever reason to stop people migrating, compared with 10 years, 50 years ago, 100 years ago. So they have more and more boundary control.

They categorize the people. Some are refugees. Even the refugees, they have the who-is-more-deserving-to-have-the-right-to-enter refugees. So when you see this whole picture, you see how the countries from the Global North create a boundary to not let the people from the Global South to go to their places. So they create categories—so that by categorizing refugees that means they can deny a lot of people to enter their countries.

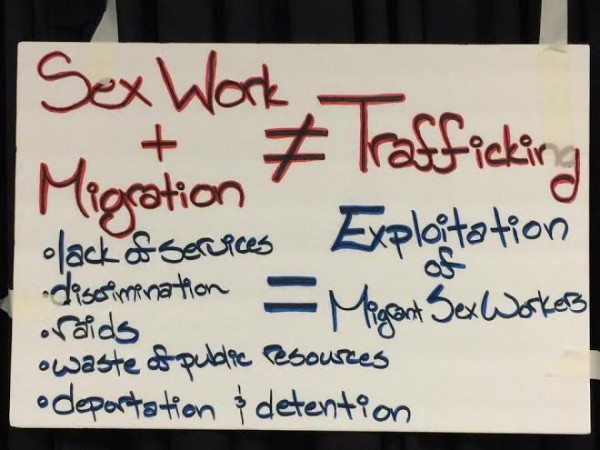

I think it’s also related to the whole anti-trafficking discourse. We think anti-trafficking is so accepted by so many people because on the surface, they say, “Oh, yeah, we are protecting the victim, we are rescuing them, they are in a vulnerable situation.” But what you see, the real thing is how the Global North—countries like [the] US, Canada, or [in] Europe—they have more and more laws to stop the people from migrating more easily to their country. And they work with the sending country to stop the people from moving. Even when people move here, they can use anti-trafficking as the reason for “rescuing”—but actually they are arresting and deporting racialized people, especially if they are from the Global South.

So I will not discuss about the migrant crisis here, because I think the migrant crisis story just makes people feel justified and comfortable about rejecting the migrants to come to their places.

Chanelle Gallant: I think that the sex workers’ rights movement in North America needs to also be taking into account and taking more seriously Indigenous sovereignty on the lands on which we live. And so, to consider the migrant “crisis” as having been produced by the Global North to a great extent, whether that’s through economic exploitation or through irresponsible climate change that’s making climate refugees out of millions of people. And then at the same time acting as though our governments have jurisdiction, completely unquestioned jurisdiction, over these lands to decide who gets to move when and where and on what basis.

And I don’t believe in that jurisdiction. I don’t agree to that jurisdiction. We’re ruled by it but it doesn’t mean that it’s right or moral. And so that’s just another element that I want to add to this conversation around sex workers questioning borders as being imposed by colonial governments that don’t have moral legitimacy. The movement would look very different and exclusion would look very different if we were respecting the legal jurisdictions of the Nations on whose lands we are living.

What sort of misconceptions do non migrant sex workers themselves often have about migrant sex workers?

Kate Zen: Well, I think a lot of sex workers who are not migrants tend to have the same misconceptions about migrant sex work as society at large and are influenced by mainstream media’s portrayals of helpless migrants in the sex trades.

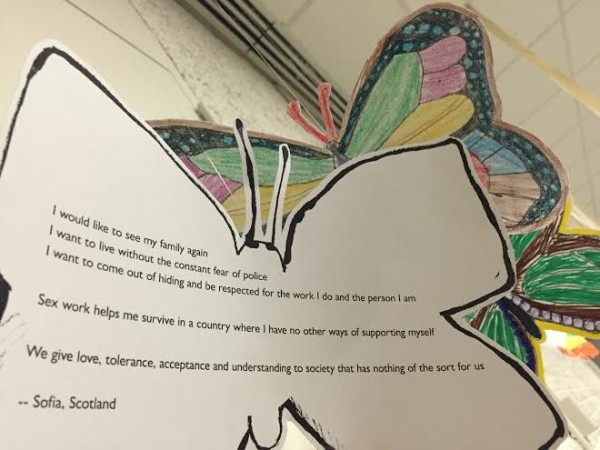

That means having hypervigilance about trafficking and having a very singular narrative about what that looks like. And focusing on migrants as only an exploited class, not understanding the ways migrants are extremely strong and resilient and use sex work as a way of resisting even more oppressive structures like borders and economic violence.

Elene Lam: I think the other thing—less talk about it, but it’s also the racism at play in people’s heads, it’s like, “why [do] these migrants come here and charge so low?” But they don’t see that actually the prices of the racialized people and the white people is reflecting the racism, right, so why some white people charge higher and people of color charge lower, it’s reflecting the racism in our society.

How do anti sex workers often use migrant sex workers as rhetorical devices? How do we best respond to that as activist sex workers—both migrant activist sex workers and non-migrant activist sex workers?

Chanelle Gallant: I don’t think anti trafficking rhetoric can exist without racism. I think it depends critically on it for its function. I also see that in Canada with this discourse around “domestic trafficking”—it plays on anti-Indigenous stereotypes that sex work isn’t part of a idea of a natural and traditional Indigenous culture, that Indigenous people can’t make the decision to migrate, that they are […] helpless dupes tricked into the sex industry.

Elene Lam: I think the antis are very smart. They choose the strategy to target the community who are more vulnerable and [who find it more difficult] to have a voice for themselves. Even when they voice themselves, [it’s difficult] because [the anti-trafficking discourse] plays so well with the racism of the society—especially Asians. Because they think Asian [means] weak, vulnerable, [that] they have no brain, and then they are vulnerable, waiting for rescue…So when the Asian identity integrates with the sex worker identity, it is so easy to use the racism in the people’s minds, that they are weak, cannot make decisions for themselves, they are so passive…So that we need to rescue them. And because on the other hand, the sex worker movement is missing this kind of voice, so that they can to use [this absence to] achieve their purpose. That’s why the MSWP is so important. Because I think the sex workers’ movement, before, is talking a lot about personal agency, and the complexity of migration is missing.

Kate Zen: I think that this is a really tricky question because it’s very easy to use people as—in general populations that are summarized by one term without desegregating different people’s experiences—it’s very easy to use people as rhetorical devices across the board, right? Obviously, in the anti-trafficking movement there’s a lot of using survivor voices and selectively choosing which survivor voices are allowed to speak to anti-trafficking and then screening out other people’s voices.

Doing effective capacity building in any kind of movement requires really prioritizing the voices and experiences of people who are engaged and stepping back to promote the things that they require and need, above all else…We have to be very, very conscious that we are only setting up platforms and not twisting the voices of people who use these platforms.

Great interview! Really insightful perspectives, especially in response to the first question.

Elene (or anyone else), if you read this, maybe you could clarify: “But they don’t see that actually the prices of the racialized people and the white people is reflecting the racism, right, so why some white people charge higher and people of color charge lower, it’s reflecting the racism in our society.”

Do you mean that the reason why many migrant sex workers tend to charge less than their non-migrant counterparts is because they feel like they can’t charge more? Like they’ve somehow embodied racist views towards themselves?

Hi Caty, you might find Nandita Sharma’s “Anti-Trafficking Rhetoric and the Making of a Global Apartheid” (Feminist Formations Vol. 17 No. 3 Fall 2005) interesting. This essay goes a little deeper into what you’ve captured in this interview.

I also wish someone would clarify Elene’s statement “But they don’t see that actually the prices of the racialized people and the white people is reflecting the racism, right, so why some white people charge higher and people of color charge lower, it’s reflecting the racism in our society.”

Do people of color charge a lower price because of a “beggars can’t choose” type of mentality? or is it because consumers (assuming White Canadian males hiring) consider minority sex workers of a lower quality than White prostitutes? Or is there another explanation for this price gap?