On December 17th, we reflect on the overwhelming reports of violence against sex workers and put together plans of action to rise above it. We experience violence at the hands of law enforcement, clients, pimps and abusive partners, and each other. Though I have never found value in comparing suffering woe for woe, it is my goal to speak only from personal experience. Call it luck or divine intervention, but my life as a sex worker has been relatively charmed. I have flirted with danger, but for the most part I managed to get by unscathed. Physically, that is. It is important to remember that not all scars are visible and that those that are not can sometimes be the deepest and most difficult to heal.

I live the life of a career sex worker who is black, a woman, and transgender. Blacks, women, and transgender people are three marginalized groups, and often the thought of encompassing all three is overbearing. I’ve looked for purpose in the eyes of strangers—whether they sat behind a desk, confused as they dissected my qualifications and wondered about my gender identity, or loomed over me, swollen with the often lethal combination of lust and disgust.

Job discrimination is a form of violence. Denying anyone the right to support themselves legally and then criminalizing the means to which they turn to sustain themselves is inhumane and deplorable. For many of us, sex work is a job of last resort. The fact is that we are rarely given an alternative. Many employers simply will not hire trans workers for fear of losing customers. Another act of violence often overlooked is theft of service, typically defined as “knowingly securing the performance of a service by deception or threat.” When theft of services happens to us, it is rape, and the damage goes beyond the monetary value of what we’ve lost. I have been the victim of both. Like many of us, I considered rape one of many occupational hazards and did nothing about it when it happened to me. How do you report something like this, and to whom?

During my time as a street-based sex worker, I personally witnessed multiple acts of violence. Some girls survived and some didn’t. It was our own Mufasa-esque circle of life, and many of us dealt with it the only we knew how: Not dealing with it at all. To live in fear is to lose money, to lose money is to starve and ultimately become homeless. The key to survival is adaptation. Learn from the violence you experience, but do not succumb to it.

I developed a strict code of conduct for myself, necessary for my survival in the business. No drugs, no excess drinking, never steal, and always use protection. I thought this was enough to shield me from the bulk of the misfortunes that befell so many before me. For a while it did, but as the saying goes, “all good things must come to an end.” I still have issues with thinking of myself as a victim, because I know what happened to me could have been worse. Despite all of what I taught myself, as safe and as smart I thought I was, no matter how much I wanted to believe it would never happen to me, it did.

Four years ago I climbed into a stranger’s car, like I had so many times before. I began to direct him toward a crowded movie theater parking lot which provided the privacy and safety necessary to conduct my business. When I noticed that he was deliberately missing turns, I attempted to open the car door while at a red light. It wouldn’t open from the inside. I turned to look at him and was met with a swift blow to the mouth. I looked up to see the barrel of a pistol. I should’ve been afraid, but I wasn’t. This was not the first time a gun had been in my face. In fact, it was the fourth. I’d never been hit and they usually wanted money, sex, or both. However, I was always able to talk myself out of the situation or escape somehow. What I lacked in strength I certainly made up for in cunning. This time was different.

“I already had to kill my best friend’s mother tonight over drug money… don’t make me have to kill you too.” He said this in a monotone and shifted his eyes back and forth like a snake. Still not grasping the full extent of the danger I was in, I joked that he was a good looking guy and could easily get any girl he desired without all this drama. He did not laugh. He only drove. Four hours later, having seduced him, apprehended the gun, and having jumped from a moving vehicle, I was battered and bruised, barefoot and carrying a gun that I later discovered was fully loaded. I was alive and filled with gratitude. Little did I know my victimization would continue.

After this ordeal, I woke up in the hospital bed with my arm handcuffed to the bed. Apparently, I’d failed to appear in traffic court for a minor offense. I hardly thought the cuffs were necessary. The SVU detective was standing over me. “Rise and shine,” he said in a condescending tone. Right off the bat, he accused me of prostitution. He said that my injuries must have been the aftermath of a “transaction gone wrong.” They weren’t. In fact things went south before we got to negotiate a price. He mentioned that he was reluctant to pursue the incident considering that I “was transgender and in a known area of prostitution.” He told me that nobody would believe me and I understood that to mean that they would think I deserved this.

I was released from jail the same day. The traffic violation had been dismissed, but like so many of my sex worker sisters, my faith in my local judicial system was forever tarnished. I thought that the the cops were supposed to be the good guys. They were supposed to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves. They were supposed to make justice a reality. At the time I wasn’t aware of excessive, unprovoked violence by police officers. I didn’t know of the beating of the trans Rodney King, Duanna Johnson, which occurred two years prior while she was being processed for a prostitution charge at a police station in Memphis, Tennessee. At this time in my life, I had no reason to expect the cops to do anything but serve and protect me. But that day I learned otherwise.

Luckily for me, the man who attacked me was caught a short time later. He admitted to everything and there was no need for me to testify after all. He was sentenced to five years in prison but was apparently released sooner, probably due to prison overcrowding. I left Atlanta and moved to Los Angeles, leaving behind as much emotional baggage as I could.

I was recently tracked down by a district attorney who wanted me to testify against this man again—–only this time he was convicted of murder. The body of an eighteen year old trans girl was found shot to death in his apartment. I am unable to confirm whether or not she was a sex worker as well, but I wouldn’t doubt it. Sex workers are often preyed upon by violent men. Many of these men are never convicted. This murdered woman’s story, like so many stories involving transgender women struck down in their prime, could’ve easily been mine. As sex workers we take necessary risks to provide for ourselves. This mustn’t be misinterpreted as a lack of self respect, or our deserving whatever violence we encounter. Instead it must be seen for what it actually is: the will to survive.

Since my time on the streets, I have become more elevated in my thinking. I have come to the realization that even at my lowest and loneliest hour, I was always a small part of a big movement. Now I grasp the importance of a solidarity that transcends the many stigmatized subsets of industrialized sex, a solidarity that goes beyond gender identity, social class, and color. I challenge all who read this to fight all forms of violence wherever they find it, to strive to better understand the plight of those who are stigmatized, and to persistently look for ways to exist in solidarity with one another.

Thank you for your strength!!!

Enticingly Yours

Velvet Steele

A really great piece!! Thank you for sharing this slice of your life. I believe it can inspire any who read it! *two thumbs way up*

Wow! What great feedback! Thanks so much! Be Well.

im so glad that the sex worker community is standing up against injustice towards sex workers of color!

Yes, it is vitally important. Thanks for reading and commenting. Be well.

Thank you both very much for your show of support.

An amazing article from a really important perspective. Framing job discrimination as violence is so essential. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you so much for reading and commenting! Be well.

This is an excellent piece that I enjoyed all while cringing — an excellent reminder to stay on my toes with my eyes and ears open. This is not an easy world to live in and I just want the author to know I read this and offer support.

Thanks so much. I really appreciate it. Be well.

[…] -A. Passion, One Black Trans Sex Worker’s December 17th […]

[…] -A. Passion, One Black Trans Sex Worker’s December 17th […]

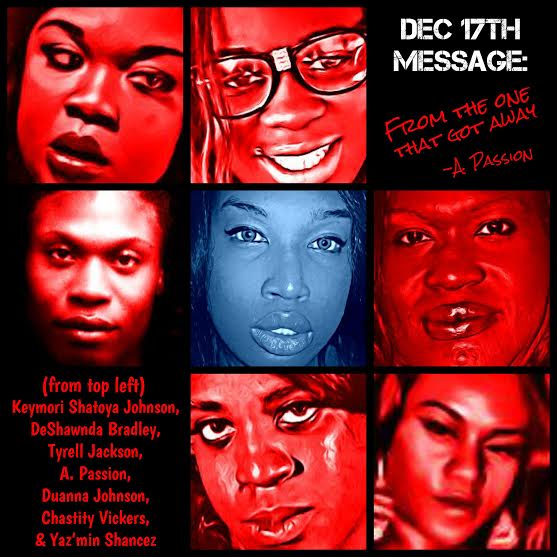

Thank you for your voice, and for being a voice for the women pictured around you.

And those not pictured.

Mz Passion thank you for writing this article. I’m also a trans sex worker and every single thing you mentioned in this piece I’ve encountered as well. Yes, you’re totally correct that job discrimination is a form of violence and that theft of services is one as well. Thank you for making those points. I wouldn’t be doing sex work were it not for the employment discrimination I’ve encountered. It angers me to no end that I live in a society that thinks nothing of denying me opportunity but will then brutalize me in so many ways for doing what I have to do to survive. Thanks again for your words and spirit. Wherever you are I hope you’re safe and well.