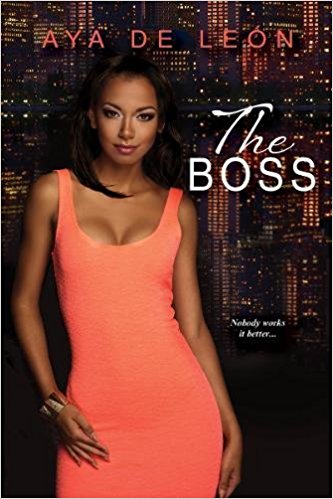

Aya de Leon’s new novel, The Boss, tackles the real issues of sex work in a criminalized society without ever coming across as preachy.

Aya de Leon’s new novel, The Boss, tackles the real issues of sex work in a criminalized society without ever coming across as preachy.

De Leon uses the experiences of sex workers and her own life to bring the reader into a diverse, vibrant, and intersectional world. As an isolated black femme sex worker living in a state with a less than 3% black population,The Boss felt like home to me, filled with characters I could recognize in my own family.

The Boss centers on two main characters who I found myself identifying with equally. Tyesha is a street smart but jaded former escort turned clinic director. Lily, Tyesha’s friend, is a Trinidadian stripper struggling to find safety while making ends meet. Lily’s teeth-sucking and reverting to patois when angry made her the realest character for me.

From Trinidadian Lily, to the various immigrants and Latinx characters, to the Chicago-raised African American members of Tyesha’s family, including a trans teen, the author has no problem dispelling the image of Blacks (and browns) as a monolithic culture.

De Leon wastes no time getting deep—whorephobia and racism within the sex industry get addressed in the first two chapters.

When the darker strippers at Lily’s club, 1 Eyed King, attempt to sign in one day to avoid their pay being docked, they’re prevented from doing so due to club politics. Illustrating her perseverance and how accustomed she is to being fucked over, Lily responds by making a new sign-in sheet and using another dancer’s phone as the time stamp while she takes a photo of the evidence that they were shut out, sending it directly to her boss.

Lily enters the story like an Amazonian force of sexuality and fear-inducing street smarts, and she proves to be all that and more. After a young, slim, blonde, white co-ed goes from being a protected favorite inspiring jealousy in the other girls to being the subject of a public attack at work, Lily is the one who physically steps in and puts her own body in the way to save the seemingly more fragile white dancer. Being aware of the privilege this other dancer has over her doesn’t turn Lily cold in the face of the attack. As always, black femmes continue to extend sisterhood to other marginalized people, and this isn’t something that’s lost or glossed over in the book.

Indeed, the black femmes of the story are consistently the ones taking action and even putting themselves in direct fire. Gunfire is almost as common as the hair digs at Tyesha in this book, and it adds up to remind you that even as a high-powered executive, Tyesha remains exposed to a world of violence and criminal elements simply as a result of being black and a former sex worker in America. De Leon acknowledges that as a black person, you aren’t out of danger just because you’re out of the hood. Your race binds you to your community for better or worse, and you’re always within arms-reach of where you came from.

Throughout the book, Tyesha struggles with sharing herself as a full person, not just fulfilling a compartmentalized role as someone who meets others’ needs. We see her become less guarded through her interactions with a rapper named Thug Woof. Eventually, she opens up to this “ally”, who seduces her intellectually only to push her away with his whorephobia when she discloses she was a full service worker. This isn’t the only ally in the book missing the mark, but the vulnerability an escort faces when letting their guard down made this experience especially painful to read about. Tyesha observes, “….it did feel like a walk of shame. Not for the sex that never happened, but for the humiliation of having gotten her hopes up and been rejected.”

Tyesha is a smart and proactively goal-oriented woman whose self-preservation skills have been honed through decades of assessing men as what they are versus what they say they are. The pain she feels being rejected by someone who couldn’t even afford to book her in her working days illustrates a power dynamic where ultimately, men are still in control.

Throughout the book, sex work is shown to be one of the few viable options for a lot of black youth in Chicago. Escorting was what allowed Tyesha a taste of college life and the freedom and funds to complete a degree. However, sex work isn’t afforded the respect “regular” jobs command, and even as a white-collar professional, Tyesha is routinely met with assumptions about her sexual availability and current activities based on her former occupation.

The author seems to be reminding us that just because Tyesha no longer supports herself as a sex worker doesn’t mean she’s escaped the stigma of it.

De Leon takes a lot of care to not present sex work as one universal experience. Tyesha has moved on from the income but still uses the skills she learned as an escort to shape the philosophy of her life. Lily moved on temporarily to Broadway but is now back to stripping with the same degree of satisfaction in life as Tyesha, minus the personal safety and plus the other marginalizing factors affecting sex work. Lily seems content with the freedom and connections stripping offers her, even if she does demand more safety and basic workers’ rights for the dancers.

In this book, sex work is never reduced to a sad temporary position for people who are down on their luck.

And when it comes to the sex scenes, not only does the author do an amazing job of using subtle hints and build up through plays on words, the passages are very female-centered and sensual to read. When I read about Woof alternating between stimulating Tyesha’s clit and penetrating her with his tongue, I felt my own body shudder from the waist down.

Adding a complex criminal scheme to the novel allows all the various settings and characters to come together for a thorough look at what life as a sex worker is really like.

It’s that constant hustle and trying to stay two steps ahead of people who you know are trying to hustle you and undoubtedly have access to more resources to do it. When you think you finally have an understanding and a straight deal, you have to watch for the script to be flipped because, at the end of the day, everyone knows the word of a sex worker is always weighed down by suspicion. There’s no police to go to, no family to rely on and accept you, and no allies who can really see things without the lenses of pity or superiority.

Tyesha isn’t just the boss of a new clinic, she’s the boss of her entire world. She illustrates perfectly how criminalizing sex workers has led us to being responsible for creating our own moral codes, career paths, and safe crossings through life without access to any of the security those who would seek to harm us have.

The book does an amazing job of at addressing not only sex worker rights but also black community issues such as colorism, hair, and pedophilia in black families, perpetuated by misogynistic ideas about “fast tail teens”.

While I definitely feel there are enough sex work and superficial race issues brought up in the book for non-Black readers to digest, The Boss struck me as so specifically written for blacks that I would even go so far as to say that non-Black POC and white readers will miss a lot of the deeper messages of the book because of their lack of exposure to them.

Parts of the novel read like a private conversation among family members. De Leon confronts a lot of the issues black activists are currently discussing among ourselves in this novel, and the way she acknowledges all sides of each question attest to years living and understanding life from a black feminist perspective. The book addresses so many problems unique to black women: the competition between black mothers and their teens for the resources of men; being forced to constantly juggle the emotionally vulnerability expected from a feminist, feminine woman with the self-protection needed for survival as a black person; and the way strong black women are vilified by white women who then turn around and run to us for protection. Black women like Tyesha’s sister and Lilly are held up as negative examples for their loud and direct speech while white women’s more insidiously bad behavior is masked by their perceived innocence.

Accepting that white-passing women’s better treatment comes by way of the world’s disdain for black femmes and that these women will continue to shit on you to affirm their place in the social hierarchy is a way of life for black women.

These are the hard discussions we need to have for women to be truly unified. Feminism isn’t always welcoming to black women and, at a time when mainstream feminism is finally being critically analyzed for its failings, The Boss is a particularly important, informative, and exciting read which will stimulate vital discussions of many black and sex worker-specific issues.