Content warning: this piece contains discussion of sexual violence.

You may have read the recent editorial in the Chicago Sun-Times, an opinion piece in which Mary Mitchell argues that sex workers who are raped by a client are making a mockery of “real” rape survivors by even considering what happened to them to be sexual assault. Luckily, the majority of commentators discussing the editorial see it for what it is: a blatantly discriminatory piece of rape apologism. While the actual piece itself has been critiqued by multiple different authors and websites, the question of how sex work, sexual assault, and consent are related is a frequent topic in the discourse around sex work and its legality. Rather than stopping at simply declaring Mary Mitchell to be a peculiarly regressive quasi-feminist, it may be more helpful to examine the ways Mitchell’s views are actually in line with how most non-sex workers see our ability to consent.

Mitchell’s piece is filled with questionable reasoning and a variety of anti-sex worker phrases. She makes sure to allude to a victim narrative by mentioning “pimps” and “trafficking” (neither of which were present in this crime), but at the same time wishes to hold sex workers accountable for our own sexual assaults. Even more strangely, her qualifications of what deserves to be called “rape” (you know, “rape-rape”) seem inconsistent. She wants us to know that she doesn’t think women are responsible for their own rape if they “dressed too provocatively or misled some randy guy,” but seems to think that a man threatening a woman with a gun for sex is somehow not really sexual assault. What’s important for her is that we sex workers put ourselves in a situation which will obviously lead to sex: we’ve already consented by agreeing to take money. “It’s tough to see this unidentified prostitute as a victim,” she writes, because it’s clear the sex worker was going to consent anyhow. What is the difference between financial stability and not being shot to death, anyways?

It would be nice if Mitchell were the only person who thought this way, but unfortunately, the world is full of people with similar opinions. I’ve heard too many men joke, “If you rape a hooker, is it rape or shoplifting?” to read this as an isolated incident. And surely enough, there is at least one recent case where officials have dismissed sexual assault charges when a sex worker is the victim. In fact, the judge in that scenario, Philadelphia’s Teresa Carr Deni, used the same exact arguments that Mitchell did: calling the sexual assault of sex workers rape demeans real rape victims; it is actually more a “theft of services” (a direct quote from both Mitchell and the judge, incidentally).

Rather than an opinion held by particularly vicious bigots, I think this is actually a belief held by most non-sex workers, including many of our clients. Sex workers, in the eyes of many, are just people who are particularly lascivious, who get into sex work because they are that into having sex with lots of people. Almost every sex worker I know has a story of a client who thought that after one or two times of meeting, the sex worker would be willing to stop taking payment for their work; clients habitually try to barter us down on the presumption that we must be getting our own payment (in terrible sex). Even people who purport to be allies might hold this view: a non-sex worker who had worked on campaigns for decriminalization once asked me as I was heading off to meet a john they thought was particularly dangerous, “What is the thrill?”

In this view, our entry into sex work is a sort of broad consent: we’ve consented to whatever a client might do to us simply by being in the life. Any ability to individually consent to one round of sex is swept away, let alone the ability to consent to certain acts and not others. This is especially true for sex workers whose demographics are already highly fetishized as “always up for it,” like trans women or black women, and especially sex workers in both those demographics.

Of course, many anti-sex work feminists might seem like they hold the opposite of this opinion with their argument that all sex work amounts to rape. But if you think about it, the two models actually are not that different at all: both of these views are based on flattening the consensual component to sex work. Regardless of whether sex work is all inherently consensual, or whether it is always sexual assault, our ability to consent to individual acts is completely denied by both arguments. We can’t consent (or withhold consent) to a single event, but only to a lifestyle. This is why prohibitionist feminists are so keen on focusing on so-called trafficking as the primary form of sex work: they are uninterested in whether we consent to each individual sexual transaction, only that we consent to our work wholesale.

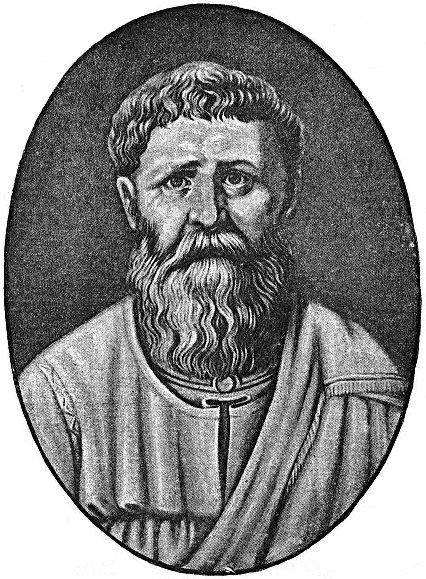

But sex workers who face sexual assault on the job complicate this picture, which is why they are written off as demeaning the real victims, whether these victims are trafficked women or “real” rape victims. Our agency and consent are seen as a necessary loss when protecting innocent women. As Augustine of Hippo wrote over 1,600 years ago in De Ordine, prostitutes are an indispensable part of society, designed to take the brunt of men’s sexual violence. Augustine’s view, that sex workers provide a sort of “safety valve” for men’s sexuality, became influential not only in the medieval period but up until the modern day. The idea here is that men are inherently prone to rape or use women sexually. Nowadays this argument usually blames hormones rather than sin, but the patriarchal belief that men can’t control their urges and so some women have to be the targets of their sexual malfeasance has remained. Many people today still see us as an underclass which doesn’t deserve the same protection as “the innocent.”

The irony is that the violent sexual assault that Mitchell describes the anonymous sex worker suffering is actually a relatively extreme example of sexual violence: being threatened to have sex at gunpoint in any other scenario would be clearly regarded by most people as rape. Mitchell seems to think that there’s a difference in the fact that her example of a “real” rape victim sustained actual physical harm (beyond the physical nature of sexual assault). One has to wonder whether Mitchell’s argument that sometimes things that are clearly rape are somehow not rape because of circumstances could not just as easily be applied to marital rape or sexual assault while drunk/on drugs. After all, these groups could also be argued to be “putting [themselves] at risk for harm,” just like Mitchell argues sex workers do. It’s also worth wondering whether Mitchell thinks other crimes, if done to sex workers, aren’t really as bad as they would be if done to a non-sex worker. Is it truly murder if a trans woman is killed while escorting, or a “workplace accident”?

Of course, the larger picture here is that our culture is saturated with messages that tell women and other marginalized people that their sexual assault doesn’t really count. Our experiences are minimized and we are left with an inability to articulate what exactly has happened to us. If we are told that something which seems to be blatantly sexual assault is not rape, then what about sexual violations that are more murky? As a person who has been sexually assaulted while working, it was hard for me to even wrap my head around how to think about my rape. Within a culture that both promotes and supports rapists, and hates sex workers by treating us as unrape-able, it was hard for me to not take in those internalized messages and dismiss my own experiences.

I want to believe that Mary Mitchell actually cares about rape victims in some twisted way. But there’s a tragic irony in the fact that in her violent bigotry against sex workers, she is supporting the foundational scaffolding of rape culture. Both Mitchell and the prohibitionist anti-sex work political faction want us to believe that they care about women’s agency and their safety from sexual assault. However, by making it so that we have no ability to consent or not to specific sex acts, they actually negate sex working women and other sex workers’ experiences of sexual assault.

Powerful piece, Petra! Thank you for writing this, I was nodding and making duck-face the whole time in agreement. A person can have boundaries and have those boundaries violated no matter his/her/their profession.

This is a really great point: “One has to wonder whether Mitchell’s argument that sometimes things that are clearly rape are somehow not rape because of circumstances could not just as easily be applied to marital rape or sexual assault while drunk/on drugs. After all, these groups could also be argued to be “putting [themselves] at risk for harm,” just like Mitchell argues sex workers do.”

On that note, would an escort who’s flat broke and at risk of being evicted be putting herself at risk for harm by NOT working? We all make choices in life. Why is choosing to sell sex a more terrible and more vilified form of harm than choosing homelessness?

What is so fucking special about sex, that makes it so evil?

Setting aside “sexual assault”, the idea that, “sex workers can’t consent”, seems to be a theme. Oh, its not, “They consented by merely doing their jobs.”, in this case, but no, I mean from the “protect the victim” angle I have been arguing for a while with someone who states, “If someone is paying you for it, you are automatically a victim, and therefor cannot be said to have consented to do it.” This person doesn’t want to end “all” sex work, they don’t much like some of the laws that currently exist to stop it, but they also a) can’t define what the F actually defines the dividing line between “sex work that is OK, and a prostitute”, in any believable fashion (pointing out that even porn stars may, in certain cases, be “paid” money to have sex with people they don’t know, who they didn’t pick out for themselves, even if it is a rarer thing, just got me, “Its not the same thing at all!” Then there was the whole professional dom/sub issue, which, again, she didn’t see as “the same”, but which I attempted to point out the law, and the people writing the laws, are very unlikely to make distinctions about.), and b) can’t explain what *other* solution should be used to fix the problem.

She, for example, seems to love the whole “end demand” idiocy, which I compare to having desperate people, working on badly constructed, and just short of sinking, boats, then, instead of going after the boat owner, or creating regulations, and enforcing them, for boat safety, you a) let the owner hide, b) watch while the desperate workers, hired to run the boats, go down with them, without actually trying to rescue them, and finally c) claim that you are “helping the real victims (i.e., the workers), by, instead, bankrupting the workers, and arresting the people buying cruise tickets.

Its a very bizarre, alternate, universe that “sex work” seems to live in, in which “protecting and saving victims”, means, “Let the building burn down, around the hotel staff, while arresting the people renting rooms.”, for another example I pointed out. I dare say that there is no other industry in which the prevailing solution to a problem is to harm the victim, for their own good, while not only failing to pursue the victimizer, but redefining the “buyer of the service”, as the one creating the victims, all while claiming the justification for this is, as the fool I argued with did, that, “The reason they are victims is because you can’t ‘consent’ to sex for pay. The money makes it impossible!”

But, I guess this is just sort of the flip side argument – “We need to save the victims, since you can’t consent to something someone is paying you to do.” vs. “It can’t be assault, because you chose a job, in which you already consented to sex with the person you claim assaulted you.” It makes me angry, but.. not surprised, sadly, that you can have people argue **both** of these contradictory things when talking about the same job.

The gun. The utter terrifying fact of the gun being minimised in a clear case of rape around this whole incident is what astounds me also. The openness of the rape culture apologists begger belief. Great article, the critical aspect of consent needs to constantly be put forth, thanks for publishing.

[…] tend to ignore sex workers of other genders) can consent to sex work, despite the loud and repeated claims to the contrary by sex workers themselves. In the same way that misogynists claim that no sex worker can be raped […]

[…] tend to ignore sex workers of other genders) can consent to sex work, despite the loud and repeated claims to the contrary by sex workers themselves. In the same way that misogynists claim that no sex worker can be raped […]

[…] there are also those who believe that prostitutes cannot be raped since we are apparently ready to go to bed with anyone at any time. Others again believe the exact […]

[…] están aquellos que creen que las prostitutas no pueden ser violadas, ya que aparentemente estamos listas para acostarnos con cualquier persona en cualquier momento. […]