In the early 00s when I was in journalism school, my professors were feebly trying to bestow me and my fellow students with the skills required to work in print media. Sure, they said, the future of journalism is online. But none of them could quantify what that meant or how to teach it. The… Continue reading So Long, Gawker, Thanks For the Coverage and the Bylines

What Does Amalia Ulman’s Instagram Art Mean for Sex Workers?

‘Up-and-coming’ no longer describes Argentine-born Amalia Ulman. Her recent work– a secret Instagram photo series mimicking the online persona of an L.A. sugar baby–made some huge waves. Ulman is quickly gaining ground as an artist whose accomplishments extend well beyond speaking at the respected Swiss Institute and showing at Frieze and the 9th Berlin Biennale.… Continue reading What Does Amalia Ulman’s Instagram Art Mean for Sex Workers?

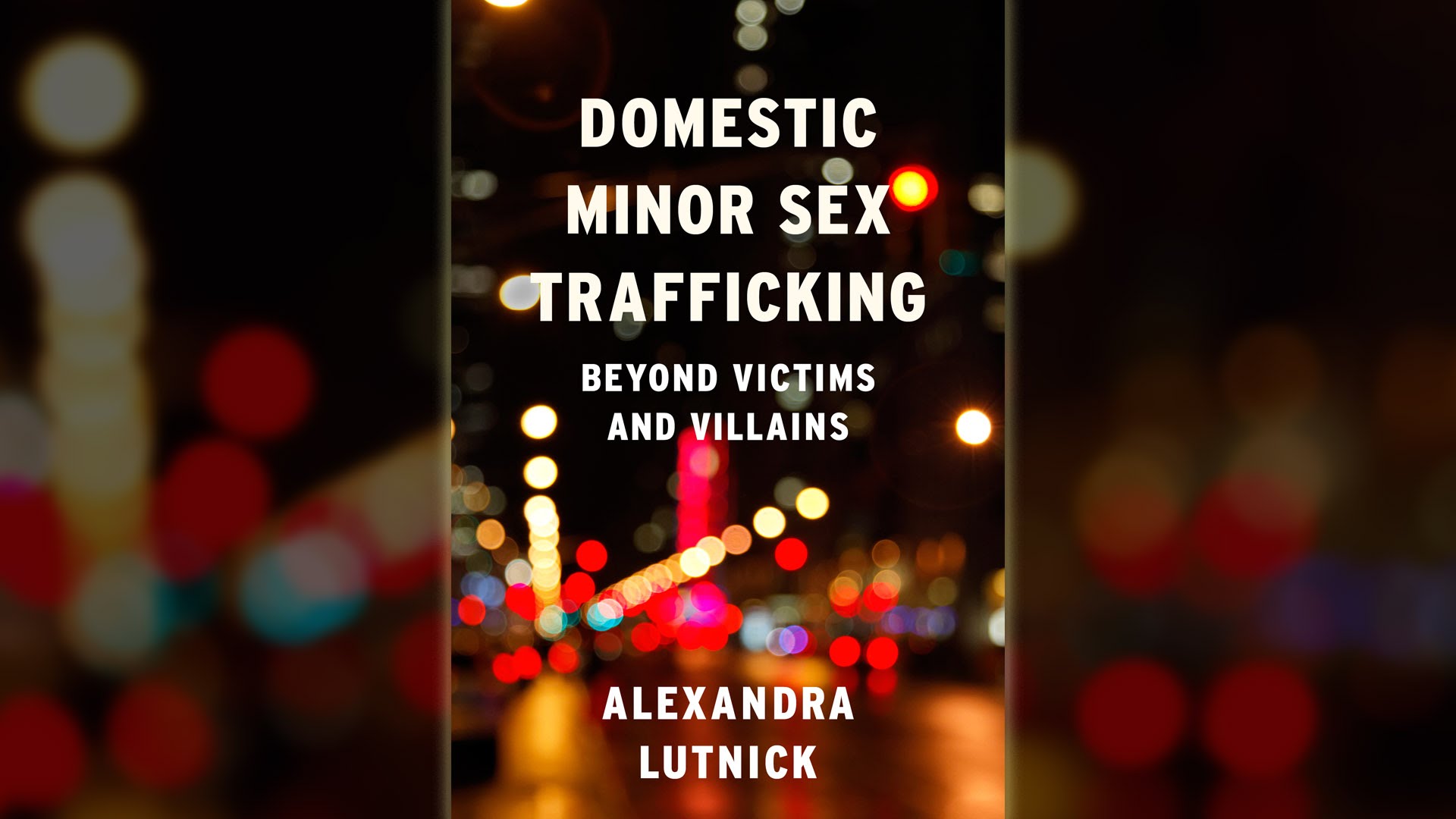

Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims And Villains (2016)

When I got arrested recently, my copy of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims and Villains by Alexandra Lutnick came along with me to jail. It’d be fair to blame me, as well as the boys in blue, but I think it’s unlikely that this is the last time this publication will see the inside… Continue reading Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims And Villains (2016)

Why Sex Workers Shouldn’t Vote Green

With contributions by Cathryn Berarovich. In this election, there is no viable option for those of us looking to build a better world. People have exclaimed, “What about Bernie?! What about Jill Stein?” And maybe a little while ago, before looking into their respective platforms, I would have said, “Okay, yeah, sure—but organize.” But fortunately,… Continue reading Why Sex Workers Shouldn’t Vote Green

So You Think You Can Fuck A Sex Worker For Free?

Sit down. I have news for you. If you’re trying to date or hook up with someone you know from their work in escorting or porn, without paying them, your chances of success are close to zero. This is true even if we favorite your adoring comments on Twitter. It may come as a shock… Continue reading So You Think You Can Fuck A Sex Worker For Free?